I’ve been covering indie games here at Kotaku since 2016 and sharing all sorts of fantastical worlds with readers. Some are loud and flashy. Others are moody. Some of the best have come from the mind of developer Cosmo D. In February, I showed off his next game, Tales From Off Peak City. In the lead up to its official release on May 15, I sat down with Cosmo to talk about jazz, sneaking around mansions, and getting players to explore off the beaten track.

This post originally appeared 5/1/20. We’ve bumped it today for the release of Tales From Off Peak City Vol 1.

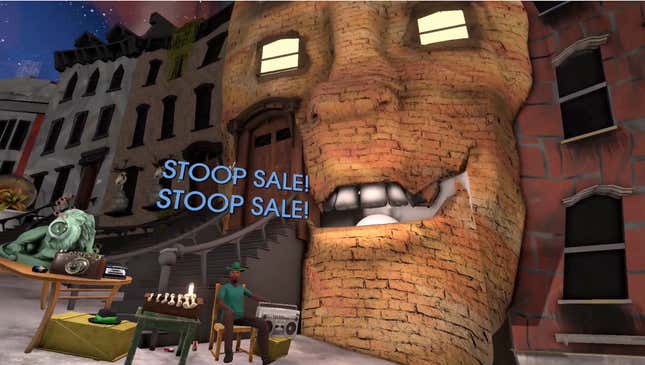

Cosmo D’s games are among the strangest and most evocative around. From the mix and match clubhouses of Saturn V to the city block of Off Peak City, he’s built worlds that blend twisting dream space with real life influences. City blocks hold friendly pizza shops and pawn stands, but there are no fire escapes. Instead, there are colorful playland-esque slides. There are basketball hoops seemingly made for giants. The dirty canal bubbles with grime, but it’s not so dirty that you can’t go snorkeling in them. Cosmo D’s games started with small spaces—a small home office with a computer, a cramped band practice room. They’ve grown to encompass neighborhoods and busy streets. There are always secrets in the back room, there are always hidden doors. The world is a playground.

Video games weren’t Cosmo’s original destination. They were a surprise. It started with music. It’s always been about the music.

Teenage cello recitals led to wedding and funeral gigs. Wedding and funeral gigs led to a college education in music composition. As he played he developed a stage name: Cosmo. It was aspirational, a chance to become someone else.

“I want to be this person on stage and be this person in digital space,” he said.

Education in music composition led to studio sessions and other work until Cosmo landed a job at a commercial music house in New York City.

Games were in the background: the dark streets of Vampire the Masquerade, the cyberpunk future of Deus Ex, the vagrant drifting through Oblivion’s open world. But music was where the work was at, and it’s how Cosmo found himself working in New York City composing music for huge companies’ advertising. Did Budweiser need some jams for a new beer commercial? Did a pillow case company want some dreamy vibes for a TV spot? The music house was packed with composers and musicians like Cosmo who had to figure out what the hell something like Chex Mix sounded like and make it into a musical reality.

“I came into contact with a lot of musicians, just moving through that space in a lot of capacities,” Cosmo said over Skype. “People who were doing it. People who were making it work.”

The experiences merged together. Knowing the folks who were doing it and meeting the demands of commercial art production led to a lesson: “commit to creative ideas but commit to polish.”

Cosmo D’s first game was 2014’s Saturn V. It was a chance to move out of the linear space of composition into the third dimension. Self-described as a “mood board,” Saturn V features an explorable clubhouse with themed rooms: a band practice room, a night club, and a room with a computer. Each room represents members of the band Archie Pelago, of which Cosmo is a member. It’s a mish-mash of the things that were helping Cosmo figure out what he could do with a game engine like Unity, and how to mix music and exploration.

He iterated on the experiment in 2015 with the release of Off Peak. It was a different type of mood board, an exploration game set in a packed train station. It was inspired by daily commutes through Manhattan’s Grand Central Terminal. The station has been meticulously maintained by the strange “overseer” who observes players from a throne. Digging around allows players to find music stands, hidden spaces, and parks with giant mushrooms. The goal is to find a ticket out of the station. Ontological Geek called it a “surreal, Kafkaesque dream.”

The games might have been “surreal,” but they came from very real places. When Cosmo started developing his next game, The Norwood Suite, he thought back to those strange wedding and funeral gigs that would often take place in large spaces: mansions, clubhouses, hotels. The Norwood Suite is set in a huge mountain resort with rooms to explore and secret tunnels in which to get lost.

“I remember being at a wedding at some old place, some old mansion in Baltimore and I went off and was just poking around this mansion,” Cosmo said. “Knowing that it’s not meant for you, but nobody seems to mind or notice that you’re there, anyway? There’s an odd tension in doing that. As long as no one’s getting hurt? I think that’s fun.”

Games like Off Peak and The Norwood Suite invite comparison to other works and other creatives. That means adjectives. Kafka-esque, Lynchian. Descriptions that point towards authors and film-makers with a penchant for dark comedy. Cosmo doesn’t mind, although he’d much rather—as with most things—bring it back to music. Strange characters? They’re pulled more from Tom Waits than Lynch. They’re not, as Lynch’s suburban casts often are, caught between cosmic forces. They are the drifting faces of Waits’ wordly ilk: Dave the Butcher, Horse Face Ethel. Jacky, who is apparently a punk, and Judy, the runt. The bizarre cast of life that are grand enough that you could place them next to Jesus or Marylin Monroe in your lyrics. A growing metaverse of shared ideas and concepts that build on each other? Miles Davis. To hear Cosmo tell it, there’s no one’s better than Miles.

“I loved that he kept searching and pushing himself out of his comfort zone,” Cosmo said of the jazz great. He points to the growth from Birth of the Cool to Kind of Blue, as well as Davis’ “electric” years. “He didn’t settle. He kept going to the next thing and surprising everyone. He didn’t have to, but I thought that was so inspiring.”

For what it’s worth, I told him I like Charlie Parker just a little bit more.

The ideas of growth and iteration are crucial to Cosmo’s latest game, Tales from Off Peak Vol. 1. In it, players must retrieve a priceless saxophone locked in the basement of a pizza shop. There’s an entire neighborhood to explore and countless characters to meet. Players can buy a camera and make a collection of pictures. If they want, they can assemble pizzas and deliver them to customers. There’s an energy to the streets, a comfort that hides an underlying chaos. Each moment is a chance to meet new people or express yourself. Delivering pizza is an excuse to do both. Smatter together some pepperoni and too much sauce, maybe top it with a little bit of flamingo meat. Walk down the block, check addresses until you find the spot. You never know who you’ll find when you get there.

Tales From Off Peak City is a cozy experience that captures the reality of living in a city. At first, it is exceedingly confusing to find your way around. Each new street seems to stretch forever. Alleys and shortcuts thrum with potential dangers, and it all feels so goddamn big. Spend some time and work a day or two? That fades. You start to know how to get from point A to point B. You know that walking to the subway means passing that one guy on his stoop. You remember that the best bar is the one that’s inexplicably beneath the pawn shop. It’s never quite “your” space, but the city can feel like home. In Tales From Off Peak City, the comfort is mixed with an oppressive edge as strange forces—G-men and other enforcers—swoop into the city blocks.

I don’t feel like the forces coming in are malevolent or benevolent,” Comso said. “They are knowing and powerful and inevitable. There’s the invisible hand of the city keeping watch over everybody.”

As for the strange men sweeping into the neighborhood? “In Off Peak City it’s more of a company and company culture.”

With that in mind, I wondered what Cosmo would do with a corporate budget. If some strange company waltzed in and gave him all the resources of a AAA game, how would that affect things? Turns out that he’d make the band bigger.

“I don’t think there would be that radical a change in my approach except more room to celebrate other people,” he said. “Make sure everyone has a seat at the table. Like being in a good jazz band passing ideas around....”

That sense of collaboration is the engine that pushes Cosmo’s games beyond the realm of quick oddball romps. It’s not really about the twisting doors or the unsettling government agents. It’s not about being weird or pulling from Lynch. It’s about building playgrounds with just enough reality that players feel welcome to explore. Unlike those commercial compositions where everything is locked on the page, the player can come in and take things in unknown directions.

“I want to mix the surreal and the relatable,” Cosmo said. “A balance of unfamiliarity and comfort… It’s an exchange. I want to see how people express themselves in my work. It’s a dialogue.”