Sometimes I imagine my brain is a collection of baskets that contain everything I know. There’s a basket for the English language, and a basket for music stuff. There’s one for Lord of the Rings lore, and another for Bloodborne monsters. Right alongside those is a worn but sizable basket that contains all my accumulated knowledge of guns.

The gun basket has been around for as long as almost any of the other ones. It’s how I know the difference between an UMP-45 and an Uzi, what an extended mag looks like, how hollow-point rounds work, and the difference between a clip and a magazine. It contains scattered knowledge of different types of body armor, door-breaching tactics, and what it looks like when a high-caliber round penetrates a human skull from medium range. Sometimes I sit and look at it. I reflect on why it exists, and how it got to be so full.

1. Hamburgers

I grew up fascinated by guns, though my family never owned one. Guns were all around me; in the entertainment I consumed, and in the toys I saw at my friends’ houses. I didn’t think about why I was so drawn to guns; I simply was.

As an adult, I’m knowledgeable about firearms to a degree that frequently clashes with how I feel about them in the real world. I don’t want a gun in my home, but I can differentiate between 5.56mm and .30-06 ammunition on sight. I think America’s gun laws are ludicrously lax, and yet I can confidently tell you the difference between an ACOG and a reflex sight. I get nervous when I’m in the airport and see soldiers with assault rifles, but I can probably tell you what kind of rifles they’re holding.

I know about a lot of gun stuff in part because of the movies and TV shows I watch, but mainly because of the video games I play. So many of my favorite games are called “shooters,” that loaded term that seems so pejorative any time it’s printed in a mainstream newspaper or magazine. I spend hundreds of hours each year playing first- and third-person shooters, online and competitive shooters, single-player shooters, and role-playing games where you do a lot of shooting. Games like Far Cry, Doom, Mass Effect, and Destiny. Some of the games I play involve wielding fantastical, ridiculous weapons—guns that shoot magical poison darts, guns that scream annoying phrases, or guns that shoot dubstep. Others involve using licensed, photorealistic recreations of actual weapons of war. I don’t like all of the shooters I play, and the older I get, the fewer of them I like. But I do still play a lot of them.

Being an American means spending every day under a shroud of gun-inflicted cultural trauma. Being an American who plays video games often means spending one’s downtime in a virtual space where people gleefully shoot one another without a second thought. There is a natural tension between those two experiences, a tension millions of us reconcile every day. Most of the time we don’t even think about it. Being a human being—American, gamer, or otherwise—means spending every day navigating the tensions between all sorts of conflicting systems and ideologies. Even the most tenuous balancing acts can become unconscious.

I think of how I nod along with my vegan or vegetarian friends when they explain the morality behind their dietary choice. I consider the affection I feel toward my girlfriend’s dog, a lovable little dope who would probably lose an IQ comparison with any random pig pulled off the line at a factory farm. I imagine a far-flung future where my nieces’ children ask me, “Uncle Kirk, did people seriously used to eat meat? Like, they’d kill and consume living, intelligent animals? And everyone was just okay with that?”

But, God help me, I still like hamburgers. They’re delicious. My taste for meat and my taste for virtual violence both involve an intellectual compromise that mostly dissipates when it comes time to like what I like. I know the analogy isn’t perfect, but the compromises I make feel similar. If I sit at my desk and think about eating animals, it seems wrong, but when I’m out for dinner ordering a ribeye, I can live with it. When I consider the fact that the majority of my free time is spent shooting virtual guns, it seems weird. When I’m merrily landing headshots in a video game, I care a lot less.

2. Close to Head-Level

“You need to be able to get to the point that just naturally, when you sight in with a sniper rifle, you have a good spatial awareness and understanding of where someone’s head is going to be,” says my instructor. I’m not at a firing range, and my instructor isn’t actually standing next to me. I’m watching an impressive gamer who goes by True Vanguard as he explains how to get better at shooting people in a video game. He speaks with the casual, clinical confidence of an expert marksman. When it comes to video games, he is one.

A couple of years ago, I decided I wanted to get better with a sniper rifle in the first-person shooter Destiny. In Destiny, sniper rifles were a high-skill weapon that, if you could use them properly, would allow you to kill your enemies, at range, faster than any other weapon. True Vanguard was an absolute beast with a sniper rifle, and the more I played competitive Destiny, the more I wanted to shoot like him.

“You need to be able to, when you initially sight in, to be relatively close to head-level so that the amount of adjustment you need to do for your target acquisition when someone comes into your sight-picture is minimal,” True Vanguard continues. He speaks with the confident drawl of a gun range instructor, casually dropping marksmanship terms like “target acquisition” and “sight picture.”

I’m listening carefully while marveling at the amazing headshots he keeps nailing in the video that’s playing behind his lesson. It’s a little distracting, actually. I want to focus on his instructions, because I want to get better, but I keep focusing on how absurdly good he is at this game.

For a moment, I reflect on what I’m actually doing, and what he’s actually teaching. He’s telling me how to make sure I put my sight on my enemy’s head, so that the bullet I fire will hit him there. He’s giving me helpful tips to be better at virtually killing people.

And here’s the thing: it feels really good to virtually kill other players—or robots, or aliens, or whatever—in Destiny! All of the guns in Destiny and its sequel feel great to use, to the point that “gun feel” is one of the most oft-cited reasons people like playing the games. There’s this satisfying “donk” that sounds when you land a headshot with a sniper rifle, accompanied by the brief rush of adrenaline that follows pulling off such a skillful feat. Fusion rifles charge and pop, shotguns emit a violent bark, and revolver-like hand cannons slam out their payload with violent precision. At its best, Destiny makes me feel like I’m dancing through a chaotic firefight, perfectly landing shots like an acrobatic action star. It’s a thrilling feeling that I willingly pursue, in Destiny and in many other games.

3. Some Kind of a Talisman

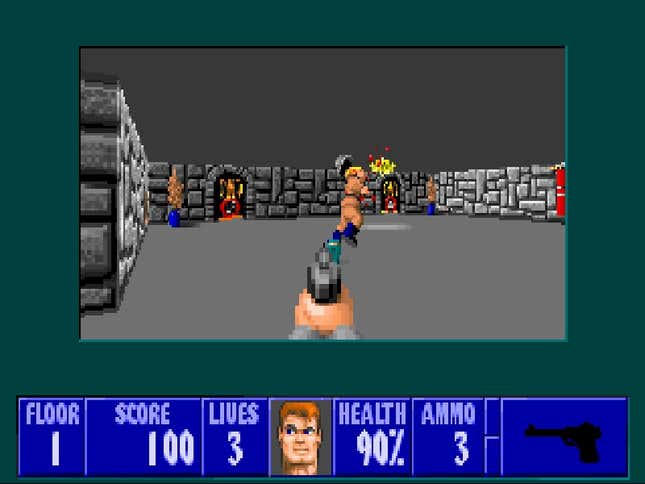

“The way that guns are represented in media is kind of like, they’re some kind of a talisman, right? You shoot somebody, and they just fall down. And that’s not really how things work in the real world.” That’s Mike (not his real name), an old friend of mine who works in law enforcement as a firearms instructor. Decades ago, Mike and I used to trade turns shooting Nazis in Wolfenstein 3D on our grade-school classroom PC. These days he works with real guns for his day job and has been training people in their use for years.

“That’s one of the things that, in training, they try to get through to you,” Mike told me as we caught up over the phone last week. “That [guns] aren’t just, you shoot somebody and they fall down and everything’s over. It’s not like the movies, and it’s not like video games. The video game representation of guns is very much like a weird sort of long-distance version of tag. Whether it’s in the hand, or the chest, or the head or whatever, you get the damage level up to a certain point and that person falls down and you win. And I don’t think that that’s in any way, shape, or form a fair representation of how firearms work.”

“I don’t think a lot of people understand what the aftermath [is],” he said, as one example of how media portrayals of guns differ from the real thing. “If you’ve never worked in medicine, and you’ve never seen a gunshot wound, or seen the consequence of something like that, I don’t think that is very well-represented anywhere.”

Mike said he gets that it wouldn’t be in the interests of most games or movies to show the bloody aftermath of a gunfight, but that “once you’ve actually seen the consequences of some of this stuff... It’s tough, carrying this weight—of the gun, and dealing with all of that stuff on a day to day basis. You have to be very careful. So the amount of care and effort that you have to exert in real life versus just how insanely cavalier you can be with a gun in a video game... You know, you’re running behind somebody in a video game, and you’ve got a gun pointed right at their back. But it doesn’t matter, right? Because you don’t have friendly fire turned on.”

Before Mike got into law enforcement, he’d never owned or used a gun. His family never had a gun. He told me most of his early impressions of guns came from movies and TV, as opposed to video games. “You and I, we started back in like, the 486 days, right? Where it was like, Doom, and Wolfenstein 3D. So you know, my perception of stuff like that, it was weird, because Wolfenstein 3D, it was almost abstract art. This sort of looks like a gun, these sort of look like people, [but] it was very pixelated.” He said he thinks that nowadays, people are probably learning a lot more about guns from video games, particularly as the guns in games become more closely modeled on relatively recent weapons.

Mike said he likes games like Ubisoft’s loot-shooter The Division, which is set in a near-photorealistic Manhattan and features detailed and realistic gun models, but that he finds them so dramatically removed from the actual experience of using a gun that he doesn’t feel like he needs to reconcile the two experiences. “It certainly doesn’t affect me on a day-to-day basis,” he said. “To me, it’s the equivalent of being a doctor and watching Grey’s Anatomy.”

In The Division, he offered as an example, your character spends the game running around the city wearing full body armor while carrying thousands of rounds of ammunition. “It is physically impossible for you to carry that much ammunition around with you, right?” he said, laughing. “That’s incredibly heavy! It doesn’t get into the fact that your body armor weighs like 30 pounds. And the weight dispersion is all off. So you could lie down and maybe not be able to get back up!”

I asked Mike if the Destiny sniper training videos I’d watched would give me an edge if I were to try to learn to use a real gun. He said that while some of the terms might carry over, that was about as far as it would go. “I mean, there’s so many more variables in real life that you have to deal with,” he said. “In the video game, it’s like, okay, I just gotta get these two things lined up, and then I click. In the real world—okay, are my arms tired? What’s the recoil of this gun going to be? How are you pulling the trigger? Are you pulling the trigger too quickly? How are you holding your gun? Is there too much pressure?”

He equated the process to learning to drive a car from a book. “You could read about driving a car. Here’s the rules of driving a car. Here’s the rules of the road. But I would not suggest that somebody who had just read the Driver’s Ed manual would then be somebody that I would just hand a driver’s license to and be like, ‘Okay, go do what you want. Now you’re able to drive.’”

4. Phoenix Force

Like Mike, I encountered fictional guns well before I played my first video game. I grew up in rural Indiana, where hunting was an ordinary weekend activity and gun ownership was commonplace. Despite that, I wasn’t allowed much interaction with firearms. Every summer at camp I’d shoot a .22 at the rifle range, but that was about as far as my experience went. My parents also discouraged me from “playing guns” with my friends. I wasn’t allowed to watch violent movies or TV shows, and our family didn’t own any gaming consoles. I was forbidden from owning any store-bought toy guns—my friends all had cool water guns, dart guns, and plain toy gun-guns, but my folks weren’t into it. We eventually reached a compromise: under my dad’s supervision, I was allowed to carve a toy rifle out of wood.

How strange it seems, all these years later, that I would have wanted a toy gun so badly that I was willing to carve one out of a block of wood! At the time, it didn’t seem strange at all. Despite my parents’ best efforts, guns were all around me; in movies, on TV, in comic books, and on the playground. Guns were sewn into the fabric of my childhood to such an extent that I never stopped to consider my relationship with them. My friends all had toy guns, and if I wanted to play guns, I needed one too. It was that simple.

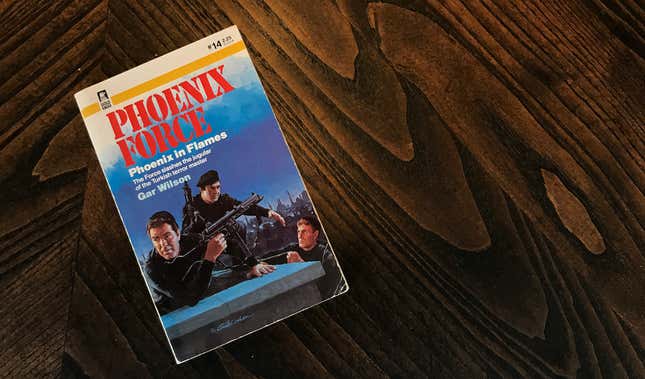

A couple years after I stopped playing with toys, I stumbled upon a cornucopia of turbo-charged gun culture on the racks of the young adult section at our town’s public library. I was browsing the stacks and discovered the Phoenix Force series, a collection of novels published in the 1980s by a multitude of authors writing under the pen name Gar Wilson.

Each volume was a slim paperback that told a spectacularly violent story of a team of international badasses, basically an R-rated A-Team. The team’s members were identified in large part by the weapons they used. Over and over the books would repeat the names and characteristics of each soldier’s firearms, almost like a mantra: Commander David McCarter used an Ingram MAC-10 and carried a Browning Hi-Power pistol. David Manning preferred a FN-FAL rifle and a Desert Eagle .357 magnum. Calvin James used an M-16 fitted with an M203 grenade launcher. Cuban commando Rafael Encizo had his own particular preferences:

In addition to the grenade launcher, Encizo carried a 9mm Parabellum Walther MPL submachine gun and a Smith & Wesson Model 59 autoloading pistol in a hip holster. The Cuban had finally accepted the fact that his .380-caliber Walther PPK was not suitable for many combat situations, but he still carried the compact, double-action automatic in a shoulder holster as a backup piece.

That’s an excerpt from Phoenix in Flames, which was originally published in 1984. It was the first Phoenix Force book that twelve-year-old me happened upon, eight or nine years later. I read those exotic brand names with fascination: M203 Grenade launcher. FN-FAL. Desert Eagle .357 Magnum. Beretta 92SB. Inspired by the books, I began writing my own little adventure thrillers, loaded with stalwart heroes, faceless villains, and buzzing parabellum death.

I recently tracked down a used copy of Phoenix in Flames on Amazon. Re-reading it as an adult, I can’t get over how clumsily-written it is, and how much of it reads like creepy gun propaganda. It reads like equal parts Reagan-era military fantasy (the narrator regularly refers to enemy soldiers as “jackals” and “trash”), high-caliber violence porn, and Guns ‘n Ammo advertorial. Every paragraph is peppered with military jargon, all “parabellum” this and “7.76mm” that. Almost every page of the book contains at least one mention of a gun’s make and model. “Hahn switched the H&K pistol to his left hand and drew the Walther P-5 from his shoulder leather.” “Manning’s hand closed on the barrel of a Soviet-made AK-47 assault rifle.” “A 3-round burst of 5.56mm slugs blasted into the side of the woman’s head. Her skull exploded, splashing blood and brains over the male terrorist’s shirt.”

I had remembered those gun names better than anything else about the characters who used them or the stories in which they featured, mostly because I’ve seen their names in so many video games since then. I’m intimately familiar with the “thoomp” of an M203 as it launches a grenade. I’m a fan of the three-round burst pattern, since it allows for better accuracy than full auto. In Uncharted 2, I always try to equip a FN-FAL (just called a “FAL” in the game) whenever possible.

Twenty-five years later, I’ve been trying to determine what it was about those trashy books that appealed to me. In my world, guns were a plaything, and real guns were an abstraction. The fact my parents had forbidden toy guns when I was younger only enhanced their appeal. Guns were taboo. I was a middle class white kid in a small midwestern town; I had never considered what it might be like to live somewhere gun violence was a regular occurrence. It was the early ‘90s, seven years before Columbine and a couple decades before the Black Lives Matter movement. I was surrounded with fictional guns while being insulated from real ones. In that way, gun culture so fully enveloped me that I couldn’t even see it.

5. The Sommelier

After a few months of mainlining Phoenix Force books, that initial spark of subversive excitement died out. Even then, I think I could tell they were nasty and hollow, and before too long I lost interest. I started reading better books, and as I got older, came to enjoy a diverse and sophisticated selection of gun-filled cinema, TV programming, and video games. My tastes have matured in the decades since I first read Phoenix in Flames, but my constant proximity to fictional firearms remains.

A lot of my favorite action movies include what I think of as the “Gun Details” scene, in which a character drops a weapon on a table, lists its make and model, and then runs down some of its technical specifications. The Gun Details scene often precedes what TVTropes calls the Lock and Load montage, which frequently takes place in front of a Wall of Guns. In Jackie Brown, Samuel L. Jackson’s Ordell Robbie famously describes a Kalashnikov AK-47 as the very best there is, for “when you absolutely, positively got to kill every motherfucker in the room.”

In John Wick 2, Keanu Reeves’ eponymous assassin meets with an Italian “sommelier” for a “tasting” that involves a detailed rundown of his firearms for an upcoming mission. Wick walks out with a set of Glock-34 and -36 handguns, an AR-15 assault rifle (“compensated with an ion bonded bolt carrier”), and a Benelli M4 tactical shotgun. I nodded with recognition as the sommelier named each of those guns, not just because I’ve read about them or seen them in movies, but because I’ve used them in video games.

Glock-style pistols, with their squarish shape and silver ejection port, turn up in everything from Battlefield to Half-Life. I’ve used AR-15-in-everything-but-name clones in games ranging from Far Cry 5 to Grand Theft Auto V. The first gun you get in Far Cry 4 looks just like Ordell Robbie’s beloved AK-47. And of course, the M4 tactical shotgun is the basis for weapons in just about every shooter I’ve ever played, from Max Payne 3 to Playerunknown’s Battlegrounds. As he talks with his sommelier, John Wick might as well be a video game character selecting a loadout.

6. In Plain Sight

The theoretical link between video games and violence has remained consistently unproven, but the link between video games and guns is right there in front of us. Video games have lots of guns in them, after all. Usually those guns are front and center, right there in the middle of the screen, and a gun on screen is only a button-press away from expressing its purpose. As Waypoint editor Austin Walker put it in a recent editorial, guns are a shortcut to violence, violence is how a lot of games express power, and power is what most video games are really about.

Over the years, some of the realistic guns we’ve seen and used in video games were there because of negotiated licensing deals between video game publishers and gun manufacturers. That system of paid promotion was best outlined in a terrific 2013 Eurogamer exposé by journalist Simon Parkin, in which he excavated a pipeline of licensing money flowing between the two industries.

“It is hard to qualify to what extent rifle sales have increased as a result of being in games,” a man named Ralph Vaughn told Eurogamer at the time. Vaughn was responsible for a placement deal that put one of the gun manufacturer Barrett’s sniper rifles into Activision’s Call of Duty franchise. “But video games expose our brand to a young audience who are considered possible future owners.” (Parkin returned to the subject in a March New Yorker editorial about video game violence in which he mentioned that both Activision and Barrett hadn’t responded to his requests to know whether the sorts of deals he reported for Eurogamer were still in place five years later.)

Parkin’s article was an eye-opener when it was published in 2013. It exposed a truth that had been hiding in plain sight: The guns we use in video games may not physically exist, but they aren’t entirely separate entities from the guns used by the military or the police. They sometimes have the same brands, and often have been painstakingly reproduced on a visual level. They sound the same, too, as evidenced by the plethora of YouTube behind-the-scenes videos showing video game sound designers firing guns in the studio or out in the field, holding boom mics up during a live-fire military exercise.

If the games I’ve played over the last ten years are anything to go by, there appears to be an assumption at many big-budget game studios that the guns in shooting games should look, feel, and sound like the real thing.

7. Another Way Forward

Not all game developers are interested in maintaining mainstream gaming’s gun-focused status quo. In 2016, Charlie Cleveland, director of the popular underwater survival game Subnautica, opened up about why he had decided to make the game gun-free. “I’ve never believed that video game violence creates more real-world violence,” he wrote in response to fan queries on Steam, “but I couldn’t just sit by and ‘add more guns’ to the world either. So Subnautica is one vote towards a world with less guns. A reminder that there is another way forward.”

And there is another way forward, as evidenced by the countless video games that, like Subnautica, don’t feature a single gun. A non-gamer could be forgiven for seeing how many popular games involve guns and coming away with the conclusion that most games have them, when that simply isn’t true. I’m a fan of shooting games, but a quick survey of my Steam PC gaming library revealed that the majority of the games I have installed are gun-free.

Of the 110 games I have installed on my PC, 42 prominently have me using a lot of guns and getting into gunfights. That means 38 percent of my installed PC games are gun games. The other 62 percent have no guns, either because they’re violent games that take place in worlds without guns (Dark Souls, Shadow of War), or because they don’t feature combat at all (The Witness, Planet Coaster). Taking into account that I generally play a lot of shooter games, that’s nowhere near as high a percentage as I had expected going in. And that’s just me; there are doubtless plenty of people with hundreds of installed games and nary a single shooter among them. (Some supplemental data: Of my top-ten most played Steam games, half feature guns and half don’t, though all of them have combat of some kind.)

One of the things I find most exciting about video games is how often they show me something completely new. Every month, I play at least one game that does something I’ve never seen a video game do before. Taken in that context, that 38 percent of my Steam library actually feels high, as does that 50 percent of my most-played games. Is this really just what I like? Do I prefer games where you shoot people, or do I just play those games because so many of the biggest, most talked-about blockbusters tend to feature shooting? There are so many things that video games can do. The fact that so many of the most elaborate, best-funded ones are about (or at least involve) guns is deflating, regardless of how well-made or enjoyable those games might turn out to be.

I’ve recently been playing Far Cry 5, a very fun new game that, were it a television program, would probably air on NRA TV. Created by Canadian studios under the French publisher Ubisoft, it imagines a fever-dream scenario that implicitly makes a case for the most extreme possible interpretation of the Second Amendment. Every good man and woman in the game’s fictional Hope County, Montana, is ready to pick up an AR-15 to fight off the maniacal, heavily-armed cult that’s been threatening their homes. Sympathetic, friendly characters embody the NRA’s infamous (and debunked) “good guy with a gun” theory. The villains are at the door, and the government isn’t coming to save us. Good thing we’ve got that bunker full of assault rifles.

Far Cry 5’s folksy heroes and cattle-country setting make its embrace of American gun culture more explicit than other games, but most popular shooters from the last couple of decades have a similar worldview. In Far Cry 5 as in its contemporaries, guns are largely presented as an unalloyed good. Of course they are; these are shooting games. Because of how the game and its world have been designed, firearms are the first and best solution to whatever challenge you might need to overcome.

“Think about what having a gun in a game usually means,” my boss Stephen Totilo wrote in a 2014 editorial. “Having a gun in a game seldom means that one shot gets fired. It means that thousands do. It means that, when we play in these gun-filled game worlds, we live in places where our heroes are merciless, where we/they aim for the head, where everyone we see is defined, at first glance as 1) a person to shoot or 2) a person to spare. There’s a heat to these worlds and a hostility. These gun-filled game worlds feel cynical, angry and, worst, reduced. So little feels possible. When two people see each other in these worlds, most likely, one will shoot the other to death.”

8. Judgment Call

In the wake of a mass shooting like the one in Parkland, Florida (14 students and 3 staff killed by a 19-year-old with an AR-15 rifle), or the 2016 Orlando nightclub massacre (49 killed by a man with a Sig-Sauer rifle and a Glock 17 handgun), or last year’s killing spree in Las Vegas (58 killed by a man with a collection of rifles including 14 AR-15s), it temporarily becomes much more difficult to talk about video games. At Kotaku, we might have been planning to run a post listing the best video game shotguns, or lauding a game series for making a famous WWII rifle so satisfying to use. We might have multiple posts that feature real-looking firearms as the top image. Sometimes, in the wake of a gun-related tragedy, we put those articles on hold. Other times we change the headline or the lead image. For a day or even a week, our easy reconciliation of thrilling virtual violence and horrific real-world violence becomes more challenging.

Whenever I hear about a new mass shooting, I find myself spending a lot of time imagining what it would be like to have been there. How would it feel to hide in a closet while a stranger with a gun stalks the hallway outside? How would it feel to watch a friend die in front of me and try to force myself to understand that this is really happening? These thoughts kinda take the wind out of my sails if I’m writing up some tips for picking the best gun in PUBG or whatever.

Around a week after the shooting in Parkland, I published an article about how much fun I was having playing Bayonetta 2 on Switch. I had snapped a screenshot for the top of the article, a typically iconic image of the titular witch striking a pose while holding her signature twin pistols.

It would’ve been a good top image. It’s an eye-grabber, with great framing—Bayonetta always knows how to strike a pose. The article ran with that image, but as soon as I saw it on our homepage, I changed my mind. Did the world really need to look down the barrel of another gun that day? Would it matter if I changed it, or was I being overly cautious and overthinking it? Did I need to worry that people who’d never played Bayonetta—a fabulous action game that’s mostly about kicking big demons in the face with high heels—might see that image and think it was yet another gun game? It was a small thing to worry about; silly, even. I changed the image anyway.

9. Assembly Required

For all those times when the distance between virtual and real-life guns contracts, it remains for the most part an easy distinction to draw. There is a yawning chasm between the instant thrill of blowing away a virtual monster and the horror of seeing someone shot in real life. I’ll laughingly watch a Sir Dimetrious sniper montage on YouTube, but recoil from videos like the recent one of Arizona police officer Philip Brailsford shooting civilian Daniel Shaver as he kneeled, unarmed, in a hotel hallway. The distance between those two things is matched by the huge difference between a video game gun and an actual gun.

That distance was cleverly explored by the computer game Receiver, a deceptively simple-looking 2012 first-person shooter made by Wolfire Games. Receiver’s name hints at the central hook of the game. In gun parlance, the receiver is the part of the gun that houses the action and firing mechanism; it’s the gun’s “brain.” Gun receivers feature prominently in Receiver, in which you play as a spy who’s been armed with one of three handguns: a Colt M1911A1, a Glock 17, or a Smith & Wesson Model 10. Seems straightforward enough, until you realize that the game is simulating a handgun’s functionality to an unusual degree.

You press a key to eject the magazine, and a different key to load in a fresh one. One key pulls back the gun’s hammer, while another lets you pull back the slide. Pulling the slide when the gun is loaded ejects bullets from the magazine, which wastes rounds you could have otherwise used. Other details in the game are more subtle, like the fact that you won’t see a gun’s sights floating in your view until you aim, because your character walks with their gun pointed at the ground.

Receiver manages to be subversive simply by making the act of using a video game gun more like actually using a real gun. In doing so, it highlights the gulf between the two things. In most games, you can accurately hip-fire by pressing a single button. In most games, you can usually reload after firing two bullets and magically keep the unused ones in your stockpile. In most games, you can’t pull back the hammer, can’t eject unused shells, and don’t need to insert bullets into a magazine one at a time.

In one way, Receiver’s relative adherence to reality insulates other video game guns from criticism—that is, a handgun in Call of Duty is nothing like the real thing, so surely it makes no difference if people play those games. But Receiver also highlights the way in which many video games function like hyper-real gun propaganda. So many games are built around worlds where a gun is the first and last option for solving a problem. They depict guns as mighty and powerful; easy to use, thrilling to master, and weightless to carry. There’s none of a gun’s fumbling mechanical intricacy or mundane maintenance, let alone the lingering physical and emotional damage usually left in the aftermath of its use. In that respect, video game guns are a carefully-told lie. They’re as close to real weapons as Captain America is to an everyday Allied soldier, face-down in the mud and praying for his life.

10. Bullet Fatigue

A game designer friend of mine, Chris Remo, often mentions on his podcast that he’s stopped playing games that have a lot of guns. He says he just doesn’t like them as much as he used to, and prefers to play other things. I asked him over email for some further thoughts on why, and when, his tastes changed.

He said that while his preference didn’t change instantaneously, one moment does stick with him: “I remember a particularly potent experience playing one of the many Call of Duty games, and being totally overcome with ‘bullet fatigue.’ Particularly the audio. I suddenly found the constant sound of gunfire totally draining.

“The older I get,” he said, “the more profoundly uncomfortable I become with the almost overwhelming obsession with guns in entertainment culture broadly, which gets harder and harder for me to totally disassociate from my much more strongly-held beliefs that real-world guns should be extremely rare and reserved for very limited purposes. I do not believe in a simple, easy correlation between fictional guns and real-life gun violence, but I do believe that entertainment and culture play one part in shaping our norms and expectations. If I lived in a country with strong gun control, I might feel less uncomfortable by the preponderance of guns in games, because any possible impact of guns in games is clearly marginal relative to the power of that regulation—but in a country that lacks strong widespread gun control, constantly encountering guns in games is an increasingly painful reminder of a part of our society with which I profoundly disagree.”

Gun instructor Mike told me that while he still happily plays shooters like The Division, he understands perspectives like Remo’s. “The older I get, the less impressed I am with the shoot-em-up stuff,” he said, adding that he now better understands the appeal of more cartoonish shooters like Overwatch and Splatoon. “Whereas, you know, Call of Duty: WWII and stuff like that, it’s getting to a point where it’s uncomfortable for me. So I understand where people could get [to that point]. Where you play these games and you’re like, man, this is just not something I can connect with as much. Maybe when you’re younger, it’s not as big of a deal. I think maybe as you age up, I think maybe people’s attitudes might shift, or have shifted a little bit.”

“As a game designer,” said Remo, “I very strongly understand why guns are such a popular tool in game development, and why they are such a satisfying tool for game players. Games are about interactivity, and interactivity relies in part on your actions having a direct result on what’s in front of you. Virtual guns are an absolutely amazing tool to achieve this—they work almost instantaneously and in extremely noticeable ways, and they work across many distances, which means their expressive potential for enacting state changes in the world is enormous. There are many, many games with guns that I love because of the creative ways they take advantage of these properties (yoooo, Far Cry 2). Despite all that, what guns represent has become too difficult for me to reconcile with those relatively transient joys, and it’s not a set of tools I personally want to use.”

Whenever Remo mentions his shifting tastes on on his show, I find myself nodding along. He’s right, I’ll think, just like I do when a vegetarian friend makes an argument against eating pork. This gun on my PC monitor represents and even glorifies one of the most broken things about America. Yet here I am staring at it, customizing it, and reveling in its virtual power for hours every night.

I still play a lot of gun games, but I sense my preferences changing as the years go by. I no longer go out of my way to play Call of Duty games, and, like Remo, increasingly find games with a gunfire-dominated soundscape exhausting. When I play Battlefield 1, I treat it more like an intense, meditative type of war-reenactment than anything fun or empowering. I’m repulsed by the glorified black-ops shenanigans in Ghost Recon: Wildlands, despite how invigorating the game could be, were it somehow divorced from its narrative context. Slowly but surely, I can feel the number of shooting games I like shrinking as my preference for non-gun-games grows. I sometimes wonder if there will be a breaking point, something that makes swear off gun-games forever. It’ll probably be a while yet.

11. Balance

Over the past month, the seemingly intractable American gun control debate has been kicked loose with a ferocity I’ve never before seen. Spurred by the resonant, furious voices of teen survivors of the Parkland shooting, hundreds of thousands of people marched last weekend in Washington and around the world to protest our government’s unwillingness to implement meaningful gun control. I want to hope that this time is different, without feeling like I have to wrap that hope in a hundred layers of jaded insulation. I want to believe that this time, something might actually change.

My inner cynic says that America is too far gone; there are already too many guns, and the NRA and its acolytes are too entrenched and powerful. Then I consider how my own relationship with guns and gun culture has changed over the years, from my thoughtless childhood fascinations to my more conflicted adulthood. I imagine the next generation starting where I am now, with so many extra years to grow smarter and do better. Maybe, in some cases, that’s just how change happens. Over the course of decades, we slowly fall out from under the thrall of something we didn’t even realize had enthralled us to begin with.

I don’t like guns, but I do like video games, and video games have helped make guns a part of my life. I’m fascinated by my relationship to both things, even as I know I’ll never strike a perfect balance between them. That’s fine; balance is a process, not an objective. Now, as ever, the process of reconciling my virtual actions with my actual self remains laced with contradiction.