I’ve been playing a lotta Nintendo Entertainment System lately, partially to make sure RetroArch’s workin’ fine on this new PC, and also just because I’m jonesin’ for some simple, classic fun. Natsume’s 1989 shooter Abadox was one of the first new-old games that came to mind, so I took it for a spin.

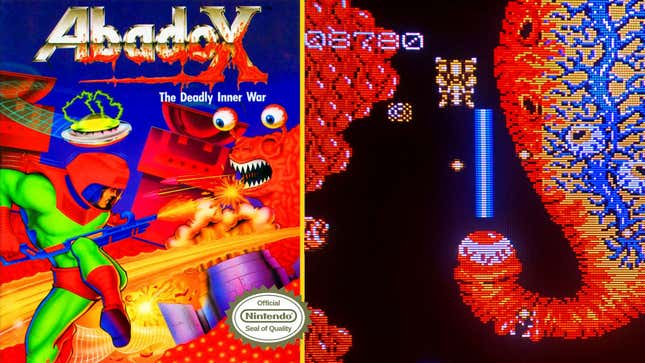

Abadox (longplay) is an alternating horizontal and vertical (downward-scrolling!) shooter that challenges your lone spaceman to assault the internal organs of Parasitis, a massive cytoplasmic alien beast that’s eaten both your planet (“Abadox”) and Princess Maria. What a cad!

The game takes Life Force’s inside-a-monster aesthetic and makes it grodier, and its memorization- and pattern-heavy gameplay is reminiscent of Irem shmups like R-Type or Image Fight. Your alien foes appear in the same spots every time, but often change behavior based on your own movement. At its most intense, the game becomes a frantic dance as you flip between struggling to stick to your pre-set plan and madly improvising to stay alive. As in R-Type, it’s hard to keep up the latter for very long.

Abadox is somewhat hard by modern standards. You usually die in one hit, and that sends you back to one of the widely spaced checkpoints with just your pathetic peashooter (only two shots onscreen at once; rapid fire highly recommended) and molasses-like default movement speed. Several gun power-ups, homing missiles, and orbiting bits can beef up your offense/defense, but you’ll never feel too safe in this “Deadly Inner War.”

Since dying in Abadox is a huge, Gradius-like setback, I decided to use save states to minimize frustration as I blasted through the game’s six stages. That took an hour or so, give or take, and in the end I wasn’t that impressed. Sure, pretty good graphics for 1989, and impressive music by the ex-Konami dude who scored NES Contra and Castlevania II: Simon’s Quest. But the experience left me unmoved.

Moreover, Abadox’s death penalty seemed so harsh—your default space dude so weak, and the stage starts so hostile—that I wondered if the game was even fair when played straight. A YouTube video confirmed that yes, you can take down any boss with the default loadout, and presumably reach them, too. That was encouraging to see. Maybe there was a fun, fair challenge buried in there. Or fair enough for the NES, at least.

As often happens, my thoughts turned to Doom. Classic Doom has a concept called “pistol start,” which means beginning a map with only Doomguy’s default pistol, fists, and 50 bullets, forsaking any weapons and power-ups acquired in prior levels. Pistol starts make each new map a fresh struggle for survival, your arsenal limited to whatever tools you find as you carefully assay your new—and newly dangerous—environment.

Before encountering Doom I didn’t know survival could feel so thrilling and fraught. I came to revel in the adrenaline rush of surviving an impossible situation by the skin of my teeth; I delighted in scrounging for bullets and medkits just to make it through the next fight. Even today, pistol starts are pretty much the only way I play Doom. It’s a different game when you always have all the power-ups. I find the journey to acquire them far more interesting.

The YouTube player’s proof of concept inspired me to take the pistol-start philosophy back to Abadox. I loaded up a save state from the beginning of the vertical-scrolling fourth stage, around where the game gets pissy, and suicided spaceguy into a wall. Sayonara, satellite shields. Farewell, five-way spread shot. Duder respawned at the start of the stage, naked, sluggish, and with the saddest peashooter this side of a badly designed Euro-shmup. The tagline for 1980 anime Space Runaway Ideon came to mind: “A long death ritual begins.”

If I didn’t wanna keep eating shit, I had to internalize some patterns. The blue blobs launched horizontally off walls, but then veered toward me at a 45-degree angle when I got close. The blue orbs, if shot, released a parasite that prevented me from firing. The large crabs flew up, doubled back, then exited the top. Tentacles controlled a lot of space, had one small weak point, and fired off a nasty revenge bullet. The wormy asteroids (kidney stones?) exploded into five worms if shot. And the damn blue scorpions, Abadox’s bastardly power-up carriers, weaved back and forth as they fled upward, attempting to deny me their cargo.

I died over and over, sometimes to the very first blob. Other times the damn power-up scorpion got me, smashing into my character because I mistimed my peashooter. Or maybe I freed the power-up—a much-needed speed boost!—only to crash into a blob as I eagerly moved to grab it. 20, 30, 40 goes. Progress, then setback. Slowly I made key gains. I learned to more deliberately aim the peashooter’s two tiny bullets, and when to stop firing. Reached a gun power-up. Made a mental note of where a particularly annoying enemy spawned, and where I should be when it did. Thought of a way to take care of another before it became dangerous.

After many deaths I put together a good enough run to reach the mid-boss guarding the mid-stage checkpoint. A pushover! There we go, stage 4 pistol starts were absolutely doable. I suicided again to pistol start from the new checkpoint, and so the process began anew. This time success came faster. And so again at the start of stage 5, and then its midpoint. My Deadly Inner War was going pretty well.

Stage 6 is the final level, and it’s nasty af to start from scratch. After sinking 30-45 minutes into its first half I can occasionally survive the initial 30 seconds. Through this forced, constant repetition I keep discovering small new foibles that help me get a crucial leg up, and if I keep at it, it’s only a matter of time before I pull off a successful enough run to reach that mid-boss, kill it, and start the final death march toward the end.

As you can see, I’m engaging with Abadox in a way that before I was not. Reassured that I could trust the designers to deliver a fair game, I stopped trying to circumvent their intended experience. When I relied on save states I was acting like a dilettante instead of a student, a tourist instead of a local. I didn’t trust the game enough to respect the lessons it wanted to teach me, and in ignoring them, I missed out on a large part of what makes this strict, precise, highly methodical shooter fun to play...what makes it, ultimately, satisfying.

All that remains is to practice more on stage 6 and string together what I’ve learned into a full-on, start-to-finish run. It won’t be perfect, but this time, I think I’m going to have fun doing it.