Frostpunk’s The Last Autumn expansion, out today on PC, is the city-building game’s best update yet. It adds several new mechanics and swaps out the threat of a plummeting thermostat for a tug-of-war between strict production deadlines and workers’ rights.

The Last Autumn, Frostpunk’s second piece of season pass DLC, takes players back to before the icy environmental collapse of the main game so they can have a hand in creating the engines of humanity’s survival. The player oversees the construction of mammoth generators that can heat entire cities, but this process is no less brutal than surviving the deep cold. Discontented workers threaten to throw a wrench in the machinery at every turn, as the world they were denied a hand in shaping slowly dies around them.

Trading snowy wastelands for the bucolic forests of Greenland in the summertime, The Last Autumn tasks you with overseeing the construction of a generator on site 113, a project so monumental it requires the simultaneous development of a surrounding colony to service the work. Where the main game has you manage scarce resources and plunging temperatures, The Last Autumn forces you to walk a tightrope between getting the generator done on time and setting aside enough resources to sustain the populace creating it.

Mining for coal and ore is replaced with harbors that can be used for fishing or receiving resources from the mainland. A new upgrade path lets you invest in engineering ways to manage the docks better and unload resources faster, while a telegraph station lets you request shipments of new workers, engineers, and steam cores vital to the generator’s construction. The result is that it’s harder to adjust strategies and economic priorities on the fly. If the ventilation plant helping filter the toxic fumes coming from the generator pit runs out of coal, getting more isn’t as easy as simply sending more workers back into a mine.

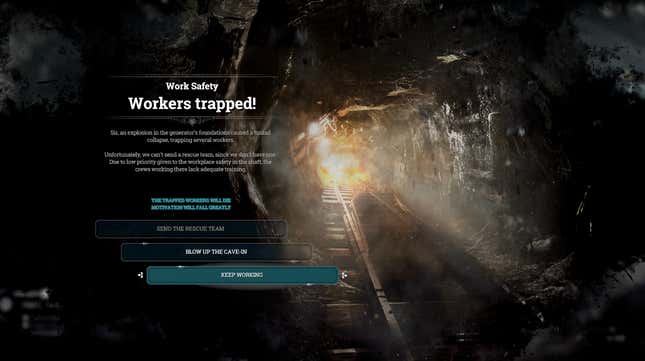

These breakdowns in the supply chain are ultimately in service of The Last Autumn’s main antagonist: labor strikes. If working and safety conditions deteriorate too much, construction grinds to a halt, jeopardizing the generator’s timely completion. Passing new laws to decrease dissatisfaction, including the creation of unions and guilds that can place further demands on how you administer the colony, offer one way of getting people back to work. Another is dumping resources into making conditions more safe. Haunting all of these compromises is the knowledge that if you don’t do what’s necessary, someone else will simply take your place.

The Last Autumn’s augmented set of challenges are more approachable than the base game, at least in the beginning: food is easier to come by and there’s no generator to worry about continually fuelling yet. But things get more perilous to navigate later on, as the cascading needs of the generator’s construction threaten to crowd out every other consideration. Three attempts and four hours later I still haven’t succeeded.

During my first attempt, I was already behind schedule when my workers decided to go on strike due to poor safety conditions. One more missed deadline and I’d be fired by the board. I tried to win some good will by giving workers extra rations, but it wasn’t enough. They were out of patience and I was out of time. So I promised to pass a law improving the quality of meals overall, putting our food supply at risk to nourish the people’s bodies. Three in-game days later I made the tough choice to extend work days to 14 hours to get construction back on schedule. Work injuries piled up, and eventually I was sacked after we missed another milestone in the project.

While the specter of humanity’s collapse helps checker the moral compass guiding my decisions in the main game, while playing The Last Autumn it’s hard not to want to do right by everyone all the time. The game encourages this mindset by attaching a motivation and contentedness bonus to every righteous act. But doing the right thing still won’t stave off the ultimate disaster. As much as The Last Autumn is a crash course in creating small miracles as a middle manager, it’s also a bit like ripping the deck chairs off The Titanic and throwing them at the impending iceberg.

Knowing where Frostpunk’s world is headed infuses each decision with a mix of pity and moral obligation. What’s the point of working people to the bone in the service of managing humanity’s inevitable decline? Building a more equitable society on the edge of armageddon might seem like a luxury, but if dozens of hours of Frostpunk have taught me anything, it’s that respect and fairness are all people will have left to give one another when the world ends.

What hints of optimism The Last Autumn does have are in the possibility that the managerial lessons the game imparts might someday, somehow, be taken back to an even earlier time, when they could help create a world order able to tackle environmental crisis more urgently. The Last Autumn made me long for a future Frostpunk expansion or a sequel based in an alternate timeline where I could find a better way to cope with the impending disaster. If Frostpunk has one resource in abundance, it’s hope.