When you find art you truly love, it doesn’t leave you. Its lessons and rhythms, its shapes and sounds, start to take up space in your mind while you’re away. You know it, you understand it, and if it’s the kind of art that gets a sequel, you just might find yourself confronted with that new sequel and think: I could have done better. We mistake our fandom for expertise. And straight up? I’m as guilty of this as anyone, especially with Paper Mario and what I thought Nintendo was doing to it.

Sometimes that franchise you love really does seem to go off the rails. Look, I truly believe that I have the perfect idea for a Star Fox game that would reinvigorate the franchise. I have zero experience in narrative design, programming, art direction, or any of the things that actually go into video games, but screw it: I feel my idea (Star Fox Dimensions) is solid gold, and Nintendo’s greatest regret will be that they never DMed me on Twitter to discuss this idea further.

If I could just be given the opportunity to take control and execute my vision, I know I could create something amazing. I’ve spent my life watching and loving these things, and I know all the flaws. What else is creating art, but avoiding flaws? Give me a blank sheet of paper, and I’ll fold it into a masterpiece.

So I was surprised this past summer when another Nintendo property took apart my hubris and did it with a smile. Paper Mario: The Origami King, released back in July on the Switch, is a lot of things: A triumph of writing and art design, a weird perpetual IQ test, a host to the most infuriating minigame I’ve played in years, and evidence that I’ve been wrong about the direction Nintendo has been taking the Paper Mario series.

Going into Origami King, my feelings about the Paper Mario series aligned with the conventional wisdom about the franchise. I had loved Paper Mario for about as long as I’ve hated it. I loved the first two entries on Nintendo 64 and GameCube, felt ambivalent toward the third (2007’s Super Paper Mario), and despised the most recent titles (2012’s Sticker Star and 2016’s Color Splash). While some outlier fans exist (some love Super; others give Splash a break for its great writing and music), most maintain a single unbreakable truth: The 2004 GameCube game Paper Mario: The Thousand-Year Door is the best game in the franchise. It is the platonic ideal of Paper Mario. And even when I go back and play it now, with 15+ years and an adult’s perspective on the story, it’s easy to see why.

Every concept introduced in the 2001 N64 original is expanded upon, if not perfected. As with the first, The Origami King is a charming JRPG adventure set in an alternate universe (sometimes portrayed as a magical pop-up book) where Mario, his friends, and their entire world is fashioned entirely out of paper and other similar crafting supplies.. The story, about Mario and his quest to recover the lost crystal stars and unlock the titular Thousand-Year Door, is daring and experimental. The writing is charming and frequently meta. For example, a nameless enemy can’t be defeated until the player recovers a letter he stole from the Name Entry menu screen first. The characters, presentation, and music all endure long after the story ends. The battle system works and serves a thematic purpose. It seemed so clear: TTYD was hard proof that the series would improve on itself with each sequel, like FF and DQ before it.

And then the game’s developers at Intelligent Systems threw away a perfectly good plan: They kept changing things.

Super Paper Mario abandoned turn-based battles for an experimental action-RPG system that erased the line between platforming and combat. Sticker Star eliminated star (experience) points, and linked the game’s economy to its returning turn-based battles by tying every action to a consumable item. Color Splash continued this trend, but added the nuance of painting enemies and objects.

Many elements of the series retained their quality, or even improved it, over time. The writing only grew more clever and hilarious even as the stories and characters became more generic. The music made an unexpected turn into full swing jazz with Sticker Star, and it was a revelation. The graphical style only became more brilliant in its attention to detail, to the point where you can count the corrugated ridges in a cardboard hill while playing Color Splash. But world-class presentation couldn’t hide the fact that the games were suffering an identity crisis. Each new title shrunk the scope of Mario’s world and abilities; by 2012, the games no longer featured any original characters. Every side character was a Toad and colorful villains had been replaced by (non-comedic) versions of Bowser.

As I observed each new Paper Mario, I felt like I was watching a slow series of train wrecks. Nintendo’s most imaginative franchise had run out of good ideas. With every game, I would just yell about how it was so simple: They just needed to make it like the old one! Why didn’t they see this?

Kensuke Tanabe, series producer for the franchise, has gone on record about the unique challenges that his team faces when working with the Mario franchise. For example, in a 2012 talk with the late former President of Nintendo, Satoru Iwata, he mentioned internal pressure to only use characters from Super Mario World. Even with this knowledge about the difficulty the developers faced as the Mario characters became a capital-B Brand, I still openly questioned the basic competence of the people who made the art I was consuming.

I did not trust Nintendo’s stewardship of the series.

In May of this year, Nintendo announced Paper Mario: The Origami King with the surprise release of a trailer. I immediately pulled up frame-by-frame analysis videos from other fans, poring through scant seconds of gameplay footage to answer the only question that mattered: Would this game be good, like TTYD, or terrible, like everything else? Had they finally come to their senses and listened to us, the fans?

No. In many ways, they ignored us completely. And made my favorite game of the year.

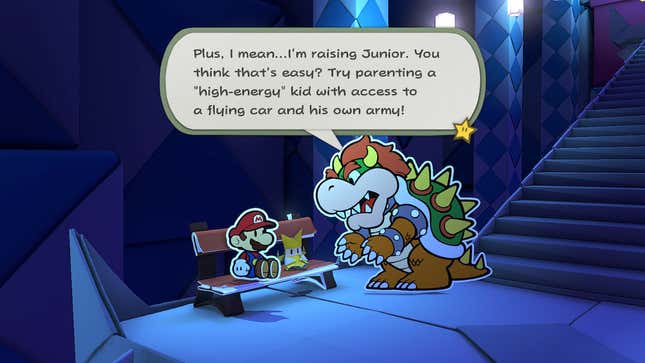

On paper (not sorry), Origami King seems to be chasing that TTYD blueprint. That’s seemingly what I wanted. A new enemy displaces Bowser by apprehending Princess Peach and her castle, forcing the Koopa King to become a comedic sidekick (a Mario RPG staple and objectively the best use of the character) throughout the adventure. In TTYD, Bowser’s side-scrolling quest to rescue/re-kidnap Peach in the shadow of Mario’s adventure still stands as a high-water mark for the series.

The writing is masterful; the soundtrack is a revelation. The game carries a haunting, horror-lite vibe that immediately made me think of TTYD’s best chapter, where Mario loses his body to a shadow-stealing ghost. The psychological tropes of body horror are cleverly applied to the main villain, King Olly, and his primary gimmick: He can forcefully bend and fold the flat-paper denizens of Mario’s world into soulless origami zombies. I remember smugly muttering “They finally did it” to myself as I settled into the game’s first hours. I was ready for a return to form.

Early in my playthrough, I began to notice what was different. And those differences morphed into something unrecognizable. It was Sticker Star all over again.

Origami King, I learned, is barely an RPG. It has far more in common with everything from The Witness to Grim Fandango to a handful of early 3D Zelda titles. The battle system combines the disposable-item concept from the previous two games with a truly original sliding-puzzle mechanic, where stats and numbers are rendered almost pointless if you can’t basically solve a Rubik’s cube first.

I wanted to hate this. I had the better blueprint; I had been carrying the idea of my/the Perfect Paper Mario Game with me for years. It was so simple, and they had gone off track again.

But then that battle music hit. I lined up my first sequence of enemies from a tricky configuration, and the music swelled as I took them out in a flawless victory. For the first time in my life, a JRPG(?) battle system had made me feel genuinely smart.

The game continued to surprise me. Every time I thought I had figured out its formula (because what is fandom, if not the ability to predict and assume?), things changed again. I went from a standard Mario RPG to an impressive recreation of visiting a tourist temple in Asia; then I was helping a Bomb-omb discover the meaning of life. From a swipe at the commercialization of culture to a tragic revenge and redemption story; from Twilight Princess setpieces to Wind Waker recreations; from a parody of the afterlife to a genuinely wholesome examination of parenthood.

Does it all work? No, how could it? But by the time I finished the game, I was happy. I didn’t expect this.

I was ready to hate Origami King because it didn’t do what I wanted. And I probably could have, if I tried. But it caught me off guard by giving me something I couldn’t have imagined, and kept doing that until its story was done. Of course, it’s easy to defy someone’s imagination when they’ve narrowed it to a pinpoint by choice, focused only on aged emotions and faded memories.

Video games can do anything. The potential of the medium is so vast that players and creators are continually facing issues that other art forms confronted years ago. They can do anything, yet the furthest my imagination could reach for Paper Mario was to “make the game from before, but bigger.” I have never been more aware of the gulf between the goals of a creative team of artists and the wants of entitled consumers (myself absolutely included) than I was while playing Origami King.

When we fall into nostalgia, we’re seeking a result that’s basically impossible; we want something old to be brought back to us, while also making us feel as good as it did the first time. When we whip out our mental blueprints and chide creators for going astray from our plans, we’re trying to lead them in a gigantic loop to a place they’ve already been.

None of the great ideas in my pocket could have helped me make anything like Origami King. The team at Intelligent Systems stuck to their own plan: Try something new with every game. Kensuke Tanabe, the game’s producer, said as much in a recent interview (via Google Trranslate): “The pursuit of innovative and unique systems is the foundation of the philosophy my team and I use to develop games. Because of this, I consider it mandatory that the combat system changes with each title.”

That quote has been thrown around online as the smoking gun for the decline of the Paper Mario franchise; it’s a victim of meddling, of a producer who seems hell-bent on ruining the secret sauce for the sake experimentation. As if we love art for its consistency and predictability; as if the moments that we hold close for a lifetime are carbon copies of things we’ve seen before.

I would absolutely love a version of TTYD on the Nintendo Switch for the same reason I want all games to be easily available to everyone on modern technology: It’s a goddamn shame that this artform is so piss-poor at keeping its own history alive and accessible, and we can’t trust corporations (even Nintendo) to be responsible stewards of that history.

But it’s worth looking deep down at why we assume that More Of The Same is good enough; why we settle for nostalgia when innovation and originality made us fall in love to begin with.

Origami King has done something I thought was impossible: It helps me love the previous games in the franchise that I spent so many salty years deriding. When I tear my eyes away from my creased and weathered “blueprint” for what this franchise should have looked like, I can see those games as the actual stepping stones that brought us here.

I can see Super testing the genre-hopping waters, and Sticker Star establishing the real-world objects that continually invade the Paper world. With its willingness to lean into the inherent weirdness of navigating a land of identical Toads (and occasional real-world objects), Color Splash explored the limits of character writing when most of your cast consists of squeaky mushroom peasants. (Note, though, that Paper Jam was a mistake. It will always be a mistake.)

Many of the best things about Origami King would not have been possible if I had actually gotten what I wanted. So forget my selfish, childish idea of being served exactly what I say I want, as I demand new creative experiences be brought to me with the reliability and consistency of a fast food menu. Now, I aim to be delighted and surprised by artists following their own plan, with minimal interference from the crowd as much as possible.

In that same interview, Tanabe said something that, like so many of his team’s games, has stuck with me:

“When we implement a new or unique system in a game, we don’t know until the release date whether the players will like it. With this in mind, there is always some risk involved in implementing a new system. However, if you avoid this risk, in my opinion it is not possible to surprise or impress the players. Lately, failure has been heavily criticized—something I’ve also experienced myself. Still, one of my core beliefs as a game designer is to take on challenges, even if they involve certain risks.”

I have no idea what to expect from the next Paper Mario game. I wouldn’t have it any other way.

Mike Sholars is a freelance pop culture writer who believes that the best way to celebrate the things you love is to roast them relentlessly. He loves video games and anime. Follow him on Twitter @Sholarsenic.