Shenmue has always straddled the line between the epic and the everyday. Yu Suzuki’s ambitious adventure game series is a story of globe-trotting vengeance and magical relics. It is also a story about helping an old lady around town, or wasting a day at the arcade. Shenmue III feels exactly like the classic that started it all, 20 years ago. It will delight those who are still fans of the series, but it will utterly baffle any newcomer who attempts to play it as a standalone game.

Sega released the first Shenmue in 1999 for the Dreamcast. A console-defining game with a massive budget, it had one of the most accomplished game designers of the day at its helm: Yu Suzuki, the Sega pioneer who breathed life into arcades with games like Hang-On, Space Harrier, and Virtua Fighter.

Shenmue was something unseen at the time, an open-world game where you could walk down the street and talk to anyone you met. You could find a part-time job, buy a soda from a vending machine, or feed the neighborhood cat. It was profoundly influential on the next 20 years of game design. By today’s standards, it’s quaint. At the time, there was nothing else like it. A real-time day-night cycle? A world full of fully voice-acted characters? Weather effects? Characters who lived out their daily lives on a schedule? These things had been done before individually, but Shenmue brought them together to craft what felt like a living world. Ryo Hazuki’s quest to find his father’s killer led us through this world and all of its details.

A sequel followed shortly after. But making Shenmue games was expensive, and once Sega discontinued the Dreamcast and left the hardware business, Yu Suzuki’s ambitious dream project died. Fans hoping for a resolution to the story were left in limbo until E3 2015, where Suzuki, now running his own development studio, launched a Kickstarter for Shenmue III that drew in many backers (including me) to become the most well-funded video game Kickstarter of all time.

20 years have passed since the first Shenmue but Shenmue III doesn’t know it. It feels precisely in step with what came before it. It is a wonderful relic whose eccentricities, while alienating by modern standards, are essential to capturing the experience and feel of the originals. If you are new to the series, it will be an abrupt introduction. This is a game for players who have already accompanied Ryo all the way through the previous two games, from Japan’s sleepy neighborhood streets to the bustling underworld of Kowloon. If this intrigues you as a new player, I cannot recommend playing Shenmue III without playing the first two games.

For players who did enjoy Shenmue back in the day, this third installment feels like stepping through a timewarp. The core experience has been preserved with astounding faithfulness. Shenmue III doesn’t radically change the series. Instead, it crystallizes it into a fresh new chapter with all of the romantic ruralism, mystery, and pulpy awkwardness that defined the series.

By the end of Shenmue II, Ryo had chased the trail of his father’s killer, the mafioso Lan Di, to a rural village in China. Here, he started to unravel the mysteries of two artifacts: the dragon and phoenix mirrors, keys to locating a massive treasure that would grant Lan Di immense power. Aided by the kindly villager Ling Shenhua, Ryo must learn more about the mirrors’ history and continue his search for Lan Di. Shenmue III picks up right where its predecessor left off—at the end of Shenmue II, Ryo was in a cave learning more about the mirrors’ seemingly magical powers; at the beginning of Shenmue III he is right back in that cave with Shenhua, only moments after where his journey ended in 2001.

The first act takes place in the village of Bailu, as Ryo follows clues to find Shenhua’s father and deals with some local bandits. For all of Shenmue’s globe-trotting, its moment-to-moment plot beats are humble. It is not full of grand battles and intrigue-packed side quests. It is mostly a game about interrogating villagers for clues on where to go next, helping out at the local store, and occasionally learning snippets of the greater plot.

This is where Shenmue III will either enrapture players or lose them. Wandering Bailu and progressing the plot mostly means talking to the right person at the right time. Ryo ping-pongs from person to person, asking for leads. They point him to another person who might, if he is lucky, know a little more. Days pass slowly as villagers go about their routines. In some cases, key characters are nowhere to be found until the late evening. Bailu is a sleepy place where the most exciting thing you might do on any given day is chop some wood at the general store for a little extra money or spar with the resident tai chi master.

Modern open-world games boast of their expansive maps—my god, Red Dead Redemption 2 has so many Skyrims in it—while also littering their worlds with side quests and dynamic events. A walk to the next town might be interrupted by a dragon attack. Cutting off the beaten path could reveal hidden treasure or ridiculous Easter eggs. The promise of modern games is that you can go anywhere and do anything, and that there’s almost always a tangible reward waiting for your when you get there.

Not so with Shenmue. Its promise is that the world is full of kind people and amazing cultures. No, you cannot climb every mountain, but you can walk down the path and talk to the hermits living on the village outskirts. No, dragons will not interrupt your journey, but you might need to stop and play hide-and-seek with a few kids. Shenmue III is a humble experience where the most interesting part of your day could very well be the conversation you have with a friend over a late-night dinner.

An early moment exemplifies this approach. After confronting local bandits and losing to their leader, Ryo resolves to find a way to defeat them. His search sends him to a seemingly abandoned temple, now home to a reclusive kung fu master. Instead of quickly learning a new technique that will trounce the enemy, Ryo is given a series of mundane tasks. Catch some chickens, practice the horse stance. Eventually, the master comes up with another challenge: find a bottle of 50-year-old liquor. So it goes that Ryo must search the village for the master’s vintage, discovering a jug at the local store that costs 2,000 yuan. An enterprising player might have a few hundred yuan in their pocket at that point, and are left to their own devices as to how to acquire the remaining funds.

Shenmue III is packed with side activities that can generate cash. That could mean chopping wood for a small pittance, or spending a day or two catching fish to sell. You might collect capsule toys and sell a rare set to a pawn shop, or else use a fortune teller’s divining of your lucky color to win big at gambling. Even with all these activities, however, buying the booze is not a quick task. If I’m being cynical, it feels like padding. In context, it’s no different than the curious training that a wise master might dole out in a classic wuxia film. The only difference is that while the movie might deploy a snappy and humorous montage of the hero’s quest, Shenmue III demands that you spend the necessary hours and hard work. Shenmue as a series is ultimately about the lessons Ryo learns on his misguided journey for revenge. If Ryo needs to learn the value of patience, so must the player.

In a 2015 Jamboroo column, former Deadspin writer Drew Magary wrote about his job as a writer and its demanding pace. He ultimately decides that it is not a grind, not a tireless and draining kind of work. “When you’re in it, it doesn’t often feel like a grind at all,” he says. “Do it right, and it feels like sailing.” Done right, Shenmue III’s slow and demanding quests do not feel like a grind. Done right, they also feel like sailing. There is joy in the work, as Drew put it.

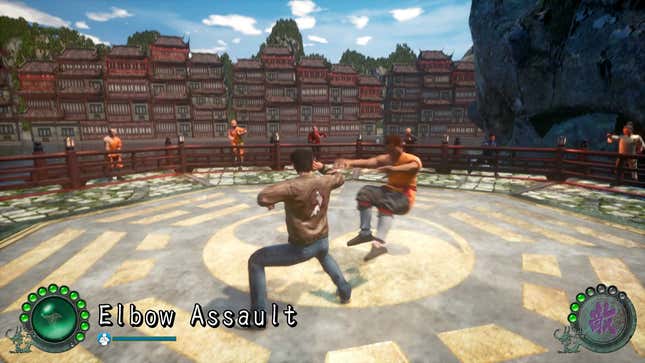

Shenmue III isn’t all scavenger hunts and fetch quests. Underpinning the day-to-day wanderings is a deceptively robust martial arts system with role-playing elements. Ryo, traditionally a practitioner of jiu jitsu, spent most of the previous game learning kung fu and continues his training here. When the time comes for a fight, the game shifts into action. Bobbing and weaving around the arena, it’s possible to dodge incoming attacks, counter with side-splitting strikes, or use special moves to knock your foe down. These moves are performed with basic button inputs akin to a fighting game’s, and there’s a variety of moves to learn either from purchasable skill books or other martial artists. Each skill’s strength can be powered up through friendly sparring, contributing to an overall level that combines Ryo’s strength and defense. Want to get stronger and hit harder? Train your skills. Want to have more health? Spend a day practicing one-inch punches or performing rooster steps.

Ryo lives or dies by this training, and players who neglect their practice will find fights against professional thugs and criminal lieutenants to be exceedingly difficult. Fights can be made easier with health potions, but these are expensive and best saved for the toughest battles. Instead, it is wiser to train at local schools or devote the early portion of your day to endurance training. This progression system was not present in previous games in the series, and helps it finally fulfill Suzuki’s original concept for the series, a martial arts RPG.

It doesn’t always work out smoothly. The aforementioned thugs and bandits are challenging opponents, hitting so hard that the most powerful bosses can drain your life in three to four hits. Even if you block carefully and dodge deftly, it’s entirely possible that a stray punch will lead to a resounding defeat.

This can be, and often is, incredibly frustrating. It brings forward momentum to a halt, and in the worst cases completely spoils what could be climactic moments. A particularly tricky boss at the end of the game was so powerful that, after spending a considerable time trying to best him, I ended up reloading a much earlier save, selling casino prizes at a pawn shop, and returning with a huge stock of healing potions. More often than not, Shenmue III left me enraptured as I sank comfortably into its world. It was the combat system’s inconsistencies that brought about the few moments where I actually yelled in frustration.

And yet, all of this makes sense. Ryo Hazuki is an 18-year-old student thrust into a world of assassins and criminals. Yes, he is a skilled martial artist and heroic soul, but he’s plunging himself into a quest for revenge that he’s ill-prepared to carry out. Time and time again, allies remark upon his haste. He is impatient, he is over-eager, he is quite frankly not ready for the task at hand. In this context, battles should be difficult. Fighting two or three hardened criminals is not a joke, not something where you can input a secret button press and win the day.

Shenmue’s raison d’être is to make the mundane feel extraordinary. Following that to its logical conclusion requires that victories be hard-won. I got frustrated with combat, and it did often feel like Shenmue III was stacking the odds against me, but this made my victories matter. I would rather play a game where fighting two criminals felt like a genuinely dire affair than the standard AAA title where I can hack and slash and shoot and explode thousands of nameless grunts. What is the point of a Master Chief when I can have Ryo Hazuki?

Part of Shenmue’s charm comes from a strange stilted quality that permeates all things. Ryo’s walking and running animations always feel a bit too much like a bounding action figure, his kicks snapping out a half-step too fast to look entirely natural. Characters fade from view as they’re culled to preserve memory load. Sometimes they walk right through each other.

Shenmue III, like its predecessors, ultimately feels like a puppet show. That’s not a knock against the game; a well-made puppet show can be just as impressive as the highest-quality blockbuster. It will, however, puzzle players who expect modern-day levels of polish. It plays out with an almost Brechtian quality that will leave modern players alienated.

From gameplay to world design, Shenmue III can seem almost antithetical to all modern expectations. That is essential, though, to how it manages to capture the Shenmue experience and continue the story without feeling dramatically out of step with what came before. Chief among the original games’ quirks, almost to a memetic status, was the voice acting. Ryo Hazuki’s English voice actor Corey Marshall’s staccato pace mixed with the games’ no-nonsense script into an almost robotic quality. Old woman crowed a little too loudly, children squawked with cartoonish cutesiness. It was like watching an old badly-dubbed martial arts film.

Shenmue III reproduces that awkwardness, with Marshall adopting the same mannerisms as he reprises his role as Ryo. It’s absolutely intentional. A suite of professional voice actors perform in Shenmue III, from Nier Automata’s Kyle McCarley to Metal Gear Solid’s Cam Clarke. Everyone plays their parts with the same excess found in previous games. These are skilled actors, some of the best in the business. But Shenmue is not Shenmue without its strange but lovable puppet people. It is a decision that will delight some fans, making them feel right at home. For everyone else, it will shatter the comfortable realism of the environmental design.

Like its predecessors, Shenmue III’s scope was cut down during development. The original plan was to have three locations: the rustic village of Bailu, the port city of Niaowu, and a final location called Baisha. Only the first two made it in. As a result, Shenmue III’s final act is incredibly rushed. Ryo’s arrival in Niaowu reunites him with an old ally and introduces multiple new friends, but there’s little time to build rapport with these characters, or to really flesh out the series’ newest villain. The final hours are a rush to move the story where it needs to go, propelling Ryo into a confrontation with Lan Di that is visually spectacular but doesn’t quite land with all of the gravitas it should.

Shenmue III is a miracle. Its uncompromising adherence to the vision laid out so many years ago on the Dreamcast is inspiring. That vision doesn’t align with today’s commonly accepted practices for video games. It is slow, it is awkward, it can be punishingly difficult. That stubbornness does not come without costs. Shenmue III leaves Ryo Hazuki’s epic incomplete, fumbling as it scrambles to prepare for whatever comes next.

I find that overreaching grasp to be oddly charming. It also feels right in step with its protagonist’s journey. For me, no other game series has approached its themes so honestly or built its worlds with such loving empathy. Ryo Hazuki marches ever onward. His thirst for revenge is folly, blinding him to the gorgeous world and wonderful people around him. Shenmue has always been building up to a moment, a realization, a character-defining turn where hate gives way to something else, something better. This message is wrapped in a play-acting package, a clumsy mixture of wuxia epic and B-movie schlock. Shenmue III is all of these things. Beautiful, sentimental, magical. Strange, clumsy, in over its head. And I wouldn’t have it any other way.

Within the context of the series, Shenmue III feels more like connective tissue than a fully functioning organ. There are a few revelations about the larger myth arc, and a one-sided battle with Lan Di, but it’s hard to say that much actually happens until the very end. Shenmue remains an ambitious series—Suzuki first imagined it as a 16-part epic—and that ambition is a double-edged sword. On the one hand, it means that every new location is lush and respectfully brought to life. On the other, it means that not even Shenmue III resolves Ryo’s tale. Its charm ultimately wins out in the end, but the finale is bittersweet. The pieces are set up for something grand but there’s a sense that most of our time was spent putting them into place for a climax that may never come. If it took this long for Shenmue III, why get our hopes up for Shenmue IV?