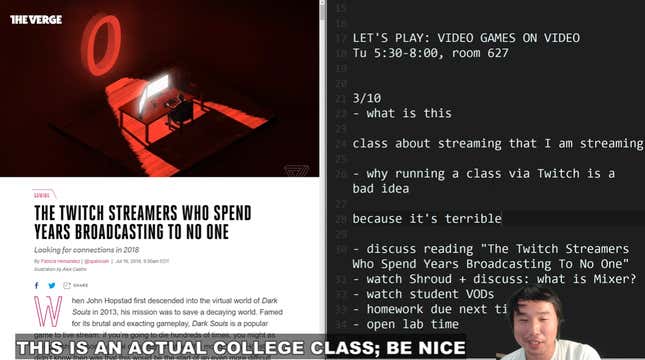

NYU Game Center professor and independent developer Robert Yang never thought teaching a class on Twitch would be a good idea, but only once he was in the thick of things did the enormity of the task dawn on him. “Oh hello, Amber,” he said to a student who’d identified herself in chat. “And hello, random people. Oh Jesus Christ. Oh no.”

On Tuesday, Yang streamed his class about Twitch on Twitch to an audience that included his students—and also a crowd of online strangers that topped out at 90 concurrent viewers. That’s not an enormous audience by Twitch standards, but it’s much larger than Yang’s usual room full of aspiring game designers. Yang (who, full disclosure, has previously taught classes that my partner took) had no choice but to teach his class online; NYU Game Center, like a growing number of universities across the country, has switched over to a remote format in hopes of helping contain COVID-19, aka the coronavirus. This presents a novel challenge for many professors, who’ve never had to keep their students engaged in class while separated by miles of distance. However, while NYU is mostly using a conferencing app called Zoom to bridge the pandemic-borne gap, Yang’s students suggested a virtual field trip to Twitch instead.

“One student joked that we should teach it over Twitch, because the class is about Twitch,” Yang told Kotaku over the phone. “I thought that was a terrible idea, and I told him that. But then I realized that sometimes terrible ideas are also entertaining and instructive and interesting. So I thought ‘Yeah, might as well try it out.’”

Yang, who regularly streams on his own Twitch channel, went in expecting friction. Classrooms encourage a different, more deliberate sort of dialogue than the madcap fireworks show of emotes and ideas that is Twitch chat, and he quickly noticed that students weren’t engaging as much as they did in class. Instead, other viewers—more accustomed to the undulating rhythms of Twitch chat—became the session’s most prominent voices.

“The students in the class stopped paying attention to chat, stopped paying attention to each other a little bit,” said Yang. “It was kind of me just trying to engage them myself and deposit knowledge in their heads. Whereas ideally, there’s a free exchange of thought and ideas... So I think I predicted the weaknesses of Twitch, and those certainly happened.”

However, he did find that the raging waterfall of randos positioned directly next to his online classroom helped captivate students in unexpected ways.

“I think it’s always very interesting for students when they see people outside of the university or academia take an interest in the things they’re studying,” said Yang. “Suddenly, it’s less of this weird academic exercise or busywork. It’s more like ‘Oh, maybe people are actually interested in this. Maybe this is relevant to the real world.’ There’s an interesting bleed from the outer world into the classroom. Some of that energy, I think, they felt.”

This particular class session drew from a book called Watch Me Play: Twitch and the Rise of Game Live Streaming by MIT professor T.L. Taylor, but it also emphasized the “underclass” of Twitch streamers who hardly get any viewers, which Taylor’s book neglects in favor of studying larger, more successful streamers. Each week, Yang has his students stream on their own channels, typically to small or nonexistent audiences. This makes them more akin to that underclass, rather than stars like Imane “Pokimane” Anys, Turner “Tfue” Tenney, or even a smaller streamer who’s just become a Twitch partner.

Another portion of Yang’s Twitch class centers around watching and discussing videos of students’ recent streams. Normally, it’s just Yang and his students reviewing their fledgling streams. This week, it was Yang, his students, and 50-some-odd viewers who’d emerged from Twitch’s purple-stained woodwork. This meant that many students were getting their first exposure to a proper Twitch audience, as opposed to one made up of friends, family, or nobody.

“That’s the experience of 99 percent of Twitch users: to have little or no audience,” said Yang. “So they really struggle with that—what it means about them. Is it a referendum on their personality? Does that mean they’re a failed artist? Does that mean no one cares about who they are or what they have to offer? ...I think it was validating for some of [my students] to get eyes on their work.”

However, Twitch audiences aren’t known for pulling punches. Yang did his best to preempt whatever barbs Twitch viewers might sling in his students’ direction with a banner at the bottom of his stream that read “This is an actual college class; be nice.” But he also wanted his students to be prepared, especially because chat was moving fast. It was impossible for him to moderate everything while scrolling back through chat and trying to address everybody’s comments.

“If you come after these real humans that I’ve been placed in charge of caring for as their teacher, I’ll totally ban you,” said Yang of the banner on his stream. “But the signal kind of goes both ways. [To my students], it was like ‘OK, steel yourself. This isn’t me nurturing you in a nice, calm way. This might be someone saying something you might not necessarily like.’”

One student, Ren Hughes, echoed Yang’s criticism of Twitch chat as a means of discussion. He was, however, “excited” to get feedback on his stream and said he gained Twitch followers in the class’ aftermath. More broadly, he doesn’t think Twitch would work super well as a means of conducting standard classes, but large, lecture-driven 101-style classes could perhaps find a place in streaming’s still-developing Wild West.

“NYU is a big university,” Hughes told Kotaku in an email, “and if you had one of those 101 seminars with 400 people all just watching one guy talk, that’d be fine I think. Plus, [it’d] give some free education to randos.”

In general, Hughes prefers the classroom.

“Taking classes from home is hard,” he said. “It’s more difficult to focus, especially because instead of being in a space dedicated to everyone learning the same thing, you’re in a place with roomates or family who aren’t focused on that, and you can’t really escape it. I’m glad I’m still getting my education, but I hope we can go back to real classes soon. This just doesn’t feel real.”

Another student, Adam Goren, thinks there might be something to the idea of teaching the occasional class over Twitch.

“Robert seemed to be convinced that teaching over Twitch was a bad idea from the get-go, but I think that it has some merit to it,” Goren told Kotaku in an email. “While class was less efficient than normal, I didn’t feel as though it was a negative experience or a waste of time. I think that this could be a very good platform for showing off student work to ‘guests’ who may drop in and offer opinions, as long as it is well-moderated.”

Despite Twitch chat’s wild ways, one non-student viewer who did speak up in chat quite a bit, critic and occasional Kotaku contributor Nico Deyo, appreciated the session.

“It was a little chaotic and definitely not as in-depth as college classes were for me when I attended, but I really appreciated using the medium to explore the medium through student work [and] readings, and [I] picked up a reading recommendation,” she told Kotaku in a Twitter DM. “I definitely started thinking a lot more about how streaming works from a theoretical perspective, which tickles me as someone who studied PR and media as a comm sci major.”

She noted, however, that it’s probably not a great setting for a class not only because students might get drowned out or distracted, but also because “lackadaisical” chat moderation is the norm on Twitch. “So many people require a lot of focus or attention, space to ask questions and react, and Twitch is perhaps a little too public, un-moderated, and visually busy,” she said.

In other ways, Yang found that streaming and teaching are not entirely dissimilar. Plucking comments from Twitch chat, translating them into talking points, and using them to fuel discussion, for instance, was not so far removed from what he already does when students are having discussions in the classroom. The difference is, on Twitch, nobody’s pausing to let somebody else speak. It never lets up. Yang called the process “stressful.” He felt additional pressure due to Twitch’s central role as an entertainment platform. As a result, he said he turned his personality up to “120 percent” during the class stream, as opposed to 90 percent for his regular, more laid-back streams and 60 percent for his regular classes. He also noted, however, that teaching is a performance more similar to streaming than you might expect.

“You quickly learn to put on a teacher persona early,” said Yang. “Otherwise, if you don’t have that teacher persona, you just get destroyed. You’ll take things too personally, or you’ll lose patience with someone. So I think teachers are maybe uniquely familiar with performing some kind of persona in front of an audience, even though we don’t usually think of teaching as performance.”

He also thinks that maybe teachers who are stranded in their homes due to COVID-19 can take some pointers from video game streamers and YouTubers, who’ve found a way to captivate audiences for hours on end while often talking about very mundane subjects. He thinks that, compared to what professors are now using to remotely communicate with their students, a less-is-more approach might be a better bet.

“Zoom has these weird tools where students can set their status. And then based on their status, it turns into this asynchronous poll that’s roughly telling you if they’re saying ‘yes’ or ‘no’ or “go faster’ or ‘go slower.” So you have to keep an eye on all these different channels. It’s a very 21st century idea of teaching... It’s like the professor has to plan a wedding, or run a party, or build this entire world that envelops everyone or something.”

It’s complex as all get out, in other words. Streaming on Twitch is often just a streamer and a game. What they’re talking about might not even have anything to do with the game, but the combination holds people’s attention. Similarly, people on YouTube will often post videos where they address an important subject for upwards of 30 minutes while footage from an unrelated game plays in the background. It’s an entire genre of video. Clearly, there’s something to it.

“I think the reason why video game streaming caught on—why [Twitch predecessor] Justin TV didn’t catch on originally but Twitch has caught on—is that games let you express some kind of performance or individuality, but without focusing entirely on your own face or your IRL body,” said Yang. “It’s your body, but not your body. It’s like a puppet. We’re watching everyone perform a little puppet theater for us. Maybe that’s what we want: talk radio with, like, a puppet show.”

Joseph A. Howley, a professor who teaches Latin, book history, and literature humanities at Columbia University, has also been mulling over the connection between teachers and streamers while instructing his students from home. He, too, thinks there’s a fundamental lesson to be learned from streamers’ basic presentation that can be applied to teaching.

“Streamers do this really interesting thing where you watch them and you watch them doing something, while they talk about both,” Howley told Kotaku in a Twitter DM. “Watching Robert apply this to pedagogy was really interesting and suggestive to me. Something as simple as having a text file open on the screen that he was writing in and then annotating and correcting made me realize that I could do something similar. Often in our seminar we look at text on our pages and then talk about it, but I could put that text in a Google doc and annotate in real time with the students while we talked about it, and then we would have a document that they could go back to later. That’s a trick that wouldn’t have occurred to me without streaming, and it’s got me creating a valuable resource I wouldn’t have used otherwise in the physical classroom.”

As for Yang, while teaching on Twitch was a struggle, he’s not ruling out doing it again for future semesters, in particular for his class about the platform.

“Maybe it’ll become a tradition,” he said. “A terrible tradition.”