There is a reasonable chance you have not heard of Jonathan Nash. However, the games journalist and comedy writer has been such an inspiration for a generation of games critics, and the generation inspired by them, that his influence has almost certainly reached you. J Nash was extraordinary, and I’m very sorry to report he has died. I also can’t wait to tell you why you will want to read everything he ever wrote.

There’s a thing about life, and the thing about life is this: it is immensely complicated.

So began a review of the wholly forgotten 1994 Commodore Amiga game Sub, in the pages of the always capitalized AMIGA POWER. It continued,

No matter how long you stick with it, there’s always something you can’t quite get to grips with or, indeed, begin to understand one tiny bit at all. Unfortunately life doesn’t come with an instruction book, but if it did, it would undoubtedly be a badly translated instruction book with lots of sentences that had a very good but ultimately unsuccessful stab at making sense. And, d’you know, in these respects, life would be a lot like this game.

Which you could accuse of leaning into cliche, were it not followed by,

So wrote Stan Wallpaper in his now standard textbook, ‘101 Extremely Contrived Introductory Paragraphs.’ Thanks, Stan. It changed my life.

The UK had a fair few influential gaming magazines, but perhaps none more so than AMIGA POWER. The magazine launched or boosted the careers of a large number of writers, many of whom would go on to form magazines you know like PC Gamer, as well as launch the careers of famous names like former games journalist and current comics writer Kieron Gillen. The magazine’s finest writer was Jonathan Nash, a unique voice whose astonishing prose forced everyone around him to aim to keep up. No one could. The best sorts tried.

I first read Nash’s work as a child, a 12-year-old reading through the magazine that made me want to be a writer, Your Sinclair. I would seek out his reviews, because they were the funniest by far, though I was still far too young to appreciate the wholly unnecessary level of skill that went into every review of a cassette-based 16-color video game based on a recent action movie. It all seeped into my brain, started defining me in indelible ways.

Without Jonathan Nash, and the cohort of writers at Your Sinclair and AMIGA POWER, there would never have been a Rock Paper Shotgun, given that at least three of the four of us who began that site somewhat viewed our games journalism careers as a sort of pasty tribute act to the man.

This is not a proper obituary, and I fail to mention some of his greatest moments, but instead just a celebration of the way the man put words in front of one another.

Jonathan had a way of putting words together that no one else would ever think to try, with results that would make me gasp as I read them. Even in an email, Nash would phrase things in such a way that I’d want to pin it to a board and dissect it to find its secret, only to find myself covered in gory letters and be none the wiser. On one occasion, when he was writing a deeply strange and complex text-based video game, I demanded of him a prize for being the first person to complete its demo. He replied, “You are correct. Nobody else has managed this, possibly because they have run out of proteins.”

Last night, as the awful news of Jonathan’s untimely passing spread among his former colleagues and friends, my messages were filled with people sharing favorite lines of his, screenshots of throwaway gags they’d never forgotten from magazines published 35 years ago, desperate searches to find scans of PC Gamer from the 90s that Future Publishing hadn’t spitefully deleted from the Internet Archive, anything to try to capture the essence of Nash’s writing and what it meant to us.

Man Of Mystery

J Nash (as many of his closest friends called him) may not even have been called Jonathan Nash. I’ve always had my suspicions. His love for Victorian obscurity has long made me wonder if he named himself after Jonathan Nash Hearder, an electrical engineer of the 19th century. Our J Nash was a deeply mysterious figure, often unseen by anyone who knew him for five or more years at a time, who then might suddenly show up on a doorstep unannounced (a thing that actually happened). He co-wrote sitcoms with people that never met him, and created archives of work that were never publicised, but always astonishing. But he will be remembered more for one era than any other: his time on AMIGA POWER.

It’s hard to convey what this magazine was to people who never read it, let alone never lived in the country where it was published. It was a gaming magazine for the Commodore Amiga home computer that was written with the energy of the music magazines of the ‘70s and ‘80s, but imbued with a silliness that undermined all its venom. Multiple companies hated it, primarily for its no-holds-barred disdain for publishers and its merciless coverage of terrible games. Team 17—the developer perhaps best known for the Worms series—loathed AP, once even issuing a lawsuit. (The letter was framed and hung on the wall of the office.) Multiple publishers blacklisted them (always a sign a publication is doing something right), and some even made abusive phone calls.

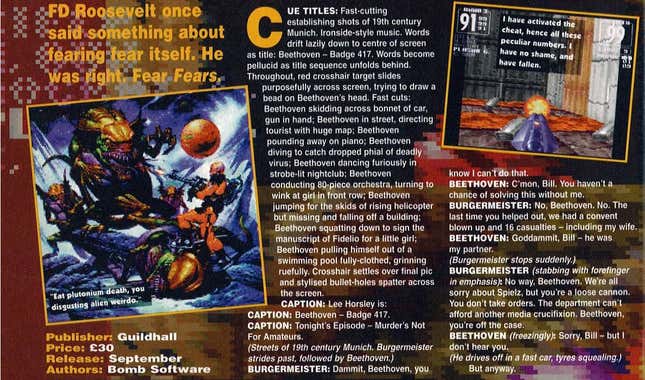

It was gently anarchic, with a priority of telling the truth, then being funny, and after that there’s nothing else that mattered. And its most powerful voice was Nash. Everyone wrote brilliantly, but Nash was the king. It was those turns of phrase, those unique bizarrities, that made even a spoof of a cop show feel fresh. Like this opening for a review of an FPS Doom knock-off called Fears.

Nash’s review of 1994's Doofus was written out as a conversation between God and a new arrival in the afterlife, punished to play the game for all eternity for his sins. No one writes reviews as conversations between God and new arrivals in the afterlife any more.

PC Gamer’s Golden Years

Ploughing through old issues of UK PC Gamer from the mid-90s, I keep finding lines of Nash’s that just delight me. A preview of Wetrix in 1997 began,

Victorian gentlefolk used to amuse their children—those who weren’t poor and reeked of chimneys, of course—with perplexing illusions. Clad in your smock, you’d receive a book illustrated with drawings of old women that, after you’d looked at them for a while, turned unexpectedly into pit-terriers. Your mind would reel and you’d be driven to run an iron foundry, wear a silly beard and slaughter prostitutes with an axe.

This is what Wetrix is like...

In another issue from the same year, Nash begins an report of his visit to the studio of developer Rowan, midway through development of fighter plane game MiG Alley, like this:

Craftily I refer to Steve Owen’s 92% Flying Corps review of Rowan’s previous game, Flying Corps. With MiG Alley, have you finally got round to contoured terrain? Flying Corps’ big unhilly map was, after all, a bit of a disappointment.

Kindly bafflement is noticeable in Rod Hyde’s tone. “The Somme is flat.” My bluff is called. The rapport is lost. Miles away, the treacherous Owen cackles fiendishly in a secret base, his elaborate plot finally played out. I resolve to twang him with a ruler.

Scour the internet, read every gaming site, and try to find me anyone opening their articles with such elaborate treats. I know I’m not. This piece goes on to contain the line, “Rod’s work on the flight models is so detailed you’d expect him to safely glide to earth if he ever fell off a ladder.” And I cannot let you down by not giving you the ending of the piece.

Once more, Rod manages not to cry at my pudding-headedness. “Classic jet dogfights are very different from WW1 or modern ones...” And who would win in a fight between Biggles and Alan Alda in a large cupboard over the disputed ownership of a Toyota Corolla? “Alan Alda, because he’d change the rules. Biggles would refuse to travel back in time to try again, as he did in his feature film, because that would be cheating. Coincidentally,” he adds warmly, “Biggles was my first WW1 flight sim.”

Miles away, the dastardly Owen raises his fist in a claw-like gesture of defiance as he falls into his own atomic reactor. I am avenged.

I’ll keep going, since you’re here and can’t leave. A preview for some ridiculous attempt at making a 3D version of Frogger contains lines like,

Frogger, readers who steeple their fingers to promote thought and healthful blood flow may recall, was a 1981 arcade game about this thing: a frog, who had to jump across a motorway and a river without perishing squashingly, in order to reach a hole in which he looked uncommonly pleased.

I could die happy if I ever wrote a paragraph that brilliant about something so utterly unimportant. Hell, if I had a brain that could think up “perishing squashingly,” I’d be twice the person.

A Legend

There are many legends about Jonathan Nash that I’ve heard over the years, all of which cast him in the most wonderful light, and in an industry rife with spoilsports and chancers, I have never heard a single person say a negative word about him in the 20-something years I’ve been in a position to have heard it. He was tremendous, the best writer of all of us, and I’m devastated that he’s gone.

In the final issue of AMIGA POWER, where all regular staff were contractually obliged to be dead by the end of their articles, Nash reviewed Team 17's pretty crappy Alien Breed 3D 2, which he’d scored 98 because “I’ve always wanted to do a false [score]... I strongly dislike the idea of neat little summaries absolving people of reading the review and await someone rushing in to say, ‘AB3D2 has scored 98%!’ at which I’ll raise my head from the crumpled heap in which I’m contractually obliged to lie, ha ha at them and then fall lifeless.” The piece ends,

Now cut mentally to a shot of my victorious assailants crowding round in such a manner as to conceal me from camera, observing, ‘Why, it’s just a cork pop-gun,’ then in a surprise twist shock reversal bluff ending saying, ‘Wait a minute - this is just some kind of highly advanced automaton big doll thing,’ and the sound of me chuckling a-ha ha ha, correctly punctuated, as you see a complicated shiny control panel that is shut into a roll-desk by my figure which passes from shot, a final pull-out showing the desk in the study from the first scene, a quietly beautiful view of Canada framed in the window. Good heavens; I’ve escaped.

With the review’s wrap-up box under the score reading,

In a doubly surprising twist shock reversal bluff post-credits sequence, there is a low shot angled upward of Jonathan standing outside looking pleased; he is then squashed by a falling anvil.

Damned anvil.

.