The original Castlevania was one of the first NES games I played. So when the sequel came out for the NES in December 1988, I knew I had to play it. Simon’s Quest mixed up the first game’s action-platforming formula and gave players a Metroidvania-style game with RPG mechanics, revolving around a curse that Dracula has inflicted on Simon Belmont.

Even back then, I didn’t love Castlevania II. I’ve watched and laughed hard at both of the Angry Video Game Nerd’s Simon’s Quest reviews, and I can acknowledge many of the game’s flaws. But there’s also a lot of things Simon’s Quest did right and which I actually really liked. It’s no mistake that Koji Igarashi attributes the existence of the brilliant Symphony of the Night, my favorite in the series, to the second Castlevania and the foundation it laid.

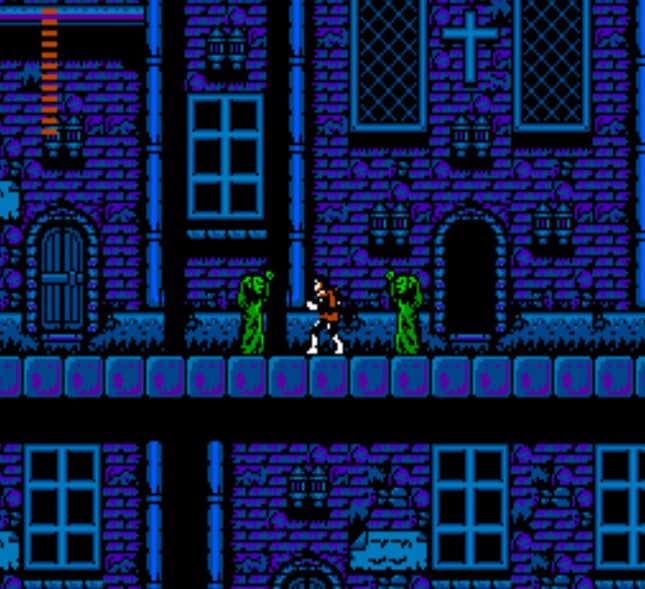

Dwelling of Doom

Last year, I wrote about my love for Zelda II. After that, a few people requested I take a look at Castlevania II next. It’s for good reason, as the two sequels have a lot in common, especially in the way they branched away from their predecessors and experimented with the formula set in the first.

One of the most interesting elements that Zelda II and Castlevania II share is that they explore the consequences of the protagonist’s actions following the first game in the series. Both Ganon and Dracula are dead. What happens after the credits roll? For Simon, his fate is harsh. Dracula cursed him the moment he died, and Simon’s body begins slowly rotting away. Devastation is obvious all throughout Transylvania and Dracula’s evil is manifested everywhere you traverse. The townspeople are deceptive and sometimes outright antagonistic. No one cares that Simon is dying, even if it was him that saved all of them in the first place.

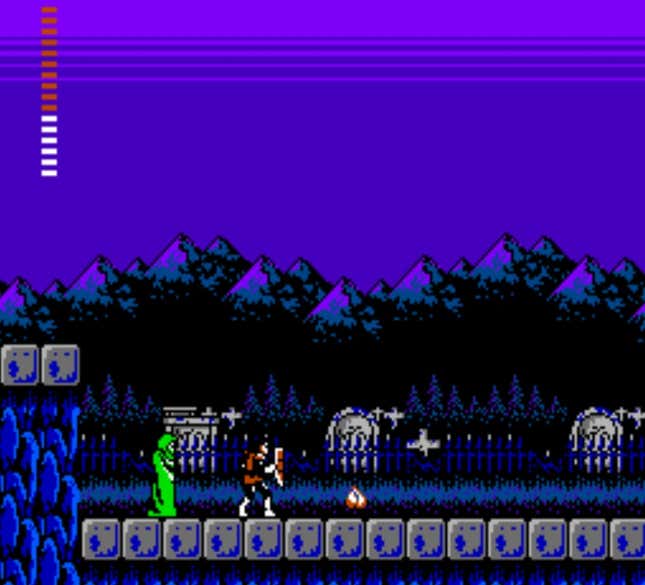

The game has a day-night cycle. In the evenings, the townspeople retreat to their houses and monsters run rampant. For the longest time, I thought (erroneously) that when the game shifted from day to night, the townspeople transformed into the zombies that haunted the town after hours. It creeped me out, but also explained why they acted so strange during the day. “Don’t make me stay. I’ll die,” an old man in the town of Ondol pleads. The pastors in the churches are in grayscale, replenishing Simon’s health but unable to leave the confines of their platform where they anxiously pace back and forth, afraid to leave. Many of the people who actually can help are in hiding, and the only way to reach them is to break down the walls they’ve built to keep intruders out.

Belasco’s poisonous marshes drain away at Simon’s health. Forests are full of dead trees. There are scared townspeople hiding in graves who only come out with the smell of garlic. Simon is trying to collect Dracula’s body parts, and the five mansions where they are being held are overrun with monsters. Corpses are everywhere, especially in the rooms that hold Dracula’s parts. They don’t even have boss monsters within because things are so decrepit. Dracula’s reign is over, but his violent legacy still casts an ominous shadow.

Simon’s Quest answers the questions of why the Belmonts have to hunt Dracula down and take him out instead of just letting Dracula chill in his castle(vania). He is a destructive force, even in death. But Simon’s first quest had changed him, which is visible in his appearance. Simon has a new outfit reflecting his darker outlook, clad in blood red and a destitute black. Fortunately, he has also been growing as a vampire hunter. Upgrades to his whip remain permanent, and every level up strengthens his ability to endure pain. His most useful sub-item is the holy water, which you pretty much have to use everywhere to uncover secrets and expose invisible pits. Even though a sense of unease pervades, Simon is better equipped to face the challenges.

The Silence of the Daylight

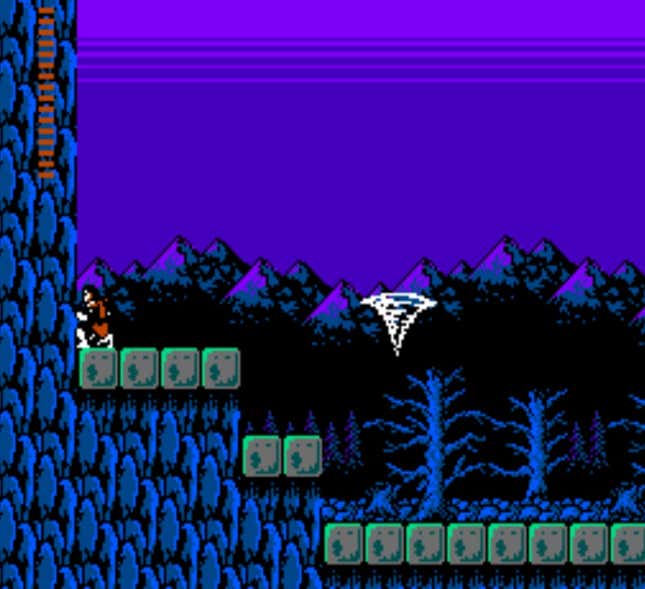

I love the fact that there’s a day-night cycle in Simon’s Quest. It’s true, as many critics have pointed out, that the transitions are jarring. But we have to consider the game in the context of the late 80s. Back then, the shifts added another layer of complexity and realism for an 8-bit game that almost no other games at the time had. All the environments get stained in ominous hues at night. Enemies become more dangerous, their health being doubled. There’s no safe haven, even in the towns. Every passing day increases the effect of the curse on Simon.

The currency system is based on hearts the enemies leave behind. I thought that was a gory, but gruesome, representation of what’s valued in their society. Kill enemies, take their hearts out, and exchange them for better weapons. What do the merchants do with those hearts? I have no idea. The townspeople were all so weird.

I never thought to question the weirdness though. It was part of the experience, and the obscurity of the puzzles only amplified the sense of Simon’s desperation. I’ve learned since then that while Simon’s Quest intended to have deceptive townspeople, their dialog boxes in Japanese would make it clear when they were being deceptive, but that nuance was unfortunately lost in translation.

What transcends languages is the bloody brilliant soundtrack. Every song is iconic, from the hopeful Bloody Tears during the day time to the dread-inducing Monster Dance at twilight. The music in the towns is arguably one of my favorite town themes in all gaming, and I can hum it all day.

Message of Darkness

There’s no getting around it; some of Simon’s Quest’s puzzles are impossible to figure out, and I couldn’t pass certain areas without help from a FAQ. (Holding the red crystal and ducking at Deborah’s Cliff is one of the more notorious examples.) I remember throwing holy water at every block in the game just in case I missed something. Fortunately, there are hidden books that give you clues, like the fact that you have to kneel at the lake with the Blue Crystal. But those are difficult to track down, and if you accidentally click through the text box, there’s no way to review the hints again.

The mansions themselves are a shrine to the remains of Dracula. His followers have lost their leader and are, in a sense, lost. They keep a part of their fallen leader encased within an orb in the hopes of his future resurrection. The jumping puzzles in these sections are tricky, as are the invisible holes in the floors that lead to plenty of frustrating drops. What’s interesting is that despite Simon’s Quest’s reputation for difficulty, the game is generous with its restarts. You respawn where you died, and there are unlimited continues. The main drawback is that when you lose three lives, you lose the hearts (money) you’ve accumulated. But compare that to Zelda II, where the loss of your three lives has you starting all the way at the opening temple as well as losing all your experience, and it doesn’t seem so bad. It required a lot of bloody tears, but I was finally able to gather all of Dracula’s parts.

Four of the pieces you possess (or “prossess,” as the game’s awkward translation has it) actually give Simon additional abilities. I found the Rib the most useful for the shield it provides against enemy projectiles, which is why I had it equipped for most of the game. I do wish that some of the effects could have been passively functional, something I also think would have been nice in Zelda II. Dracula’s Nail lets Simon break blocks with his whip, and the vampire’s Eye shows secrets—but only if you have them equipped, which meant I never got to take advantage of those abilities without removing the all-important Rib.

In stark contrast to the protagonists of most RPGs, Simon never feels like a hero. There’s no grand reward after you find Dracula’s parts. In the town of Doina, someone yells, “You’ve upset the people. Now get out of town!!” Another states, “After Castlevania, I warned you not to return.”

The final confrontation is a lonely march to face off against Dracula in his caverns underneath his castle. I remember wondering what awaited beneath. A part of me felt disappointed that there were no enemies to obstruct my way, but it’s clear this was an intentional choice, as the developers could have easily crammed the area with enemies. The final section reinforced the sense of connection with the first Castlevania. I’d already defeated its enemies and conquered the original.

When Dracula’s part are finally combined in the crypt, he doesn’t look anything like he did in the first game. I actually thought this game’s Dracula resembled a skeleton in robes with a pilot’s goggles on top of his head. The battle is easy, even without exploiting the subweapons.

Soon afterwards, I found out why it was so easy. I got the bad ending the first time I played. Simon dies. It was one of the bleakest and most depressing experiences I had. Nintendo games weren’t supposed to be this dark, were they? All that hard work I’d put in had meant nothing. I didn’t know there was a way to get a better ending—which ironically might be worse, as Simon lives but Dracula comes back to life. I’d both succeeded and failed at Simon’s Quest.

That dissonance is the theme of the game. There’s aspects of Simon’s Quest that are fascinating, and others that are jarringly frustrating. At the same time, it’s this sense of experimentation that paved the way for a more sublime symphony in future Castlevania outings. For that, I’ll always be grateful.