While Hell’s Paradise: Jigokuraku is full of gorgeous scenes, this particularly gruesome one stuck out to me: A wooden boat floated serenely along a foggy river, filled with beautiful flowers. Government officials would find a smiling corpse that had flowers growing out of its dismembered parts. It was a gruesome juxtaposition of beauty and horror that reminded me of the legendary Yu Yu Hakusho, but this manga’s more cynical outlook towards society sets it apart.

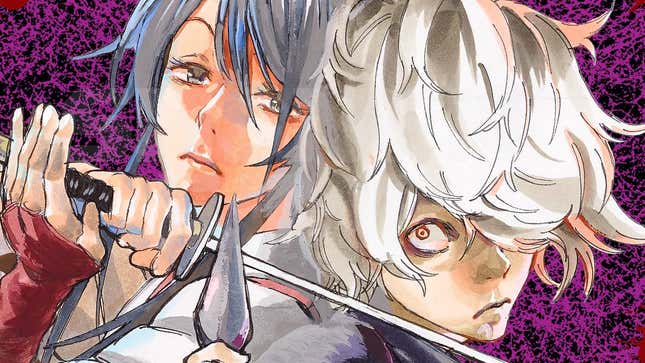

Hell’s Paradise takes place in Edo Japan, and follows the story of the legendary ninja Gabimaru and his handler, the executioner Saigiri, of the estranged Yamada Clan (who are reviled for their association with corpses). Along with other pairs of convicts and samurai, they travel to the mysterious island of Kotaku (yes, seriously) to search for the elixir of life. There, they find horrific, murderous plant monsters with unsavory plans for humanity. The executioners must partner up with the criminals they’re tasked to condemn, or risk being turned into plant-nurturing corpses. Even if they survive murder island, the crimminals would have to kill their comrades for the shogun’s pardon. While the plot doesn’t feel out of place in a shounen manga and the characters yell cheesy attack names in battle, this is not a manga where friendship or raw might can overcome all obstacles.

Despite its shounen themes and presentation, the manga deals with the darker aspects of feudal Japan. The criminals that are sent to the island are treated as disposable fodder, and made to kill each other for the shogun’s amusement. If the executioners show the wretched souls even a moment of sympathy, then they can be branded traitors and killed. Hell’s Paradise is a character study into society’s “outsiders” and the social inequalities that drive them to break the law. In the end, one quote by the executioner Shion sums it up best: “When it comes to crimes, it is the era we live in that decides such things.” His words are made awkward by the fact that the shogun is a cruel tyrant who does not value the lives of his subjects.

Hell’s Paradise isn’t the first manga to wrangle with the theme: “Having compassion is more important than following the rules.” But the incredibly high stakes make Hell’s Paradise a standout among its other action-driven contemporaries. Kindness is portrayed as a virtue, but it doesn’t save everyone. In Hell’s Paradise, the emotional peaks of friendships occur in the seconds before someone dies a gruesome death.

Worse, many of these deaths were at the hands of former allies. Many “good-aligned” characters chose to harm themselves or the people they love for the sake of maintaining the power structure under the Tokugawa Shogunate. And even when you know what’s about to happen, the inevitable heartbreak is worth reading all the way to the end of each arc. While the author Yuji Kaku is very heavy-handed with character deaths, he’s very deliberate about pairing the violence off with humane compassion. I watched Gabimaru butcher people who genuinely hero-worshiped him since they were children. Even as they died, they praised their killer and smiled joyfully until the very end. I thought that this juxtaposition between joy and death made their ends more gruesome than if the main character had slaughtered them in cold blood.

Normally, I don’t like heavy-handed character murder. Most of the time, the execution is careless and contains more shock value than emotional substance. But Hell’s Paradise is very precise in how it traumatizes its characters. Most humans in Hell’s Paradise are defined by the rigid feudal society that they were born in, split along the lines of gender, class, and bodily differences. It’s only by traveling to this monstrous island that they are able to explore new ways of expressing their humanity and forming bonds that would never exist in Japan (due to differences in social status). Hell’s Paradise understands that even the most rigid people can transform when they come into contact with the monstrous. The question remains: is change desirable, particularly if it’s monstrous, or if it opposes the shogun’s laws?

However, not all characters are treated equally by the story. Most of the female characters experience significantly less character development than their male counterparts. And although the executioner Sagiri is portrayed as the deuteragonist of the story, her role in the plot feels thoroughly unearned. When Gabimaru calls her “even stronger than I am,” I didn’t believe him. She spent most of the plot watching other people become stronger, and she never experienced high personal stakes like the Aza brothers or any of her male clan members. Yuzuriha is the comedic relief who is relatively unchanged by the monstrous island. And even though Nurugai has the traumatic background for a “coming-of-age” story, they’re the fuel for Shion’s redemption arc. Hell’s Paradise tries to grapple with the consequences of Edo-era sexism, but ultimately fails to take its women seriously.

I also feel mixed about how the narrative treats its canonically queer characters. I like that there are gay moments that occur spontaneously and without significant fanfare. Jikka’s bisexuality is portrayed as one of his many personal qualities (alongside laziness and calculativeness), rather than a gag. And one interesting bit of world-building is that the plant-based immortals of Kotaku are able to switch sex characteristics at will, which is an interesting nod to the reproductive behaviors of real-life plants. It’s a creatively daring move that fully leans into the logic of plant-hybrid people. I just wish that it wasn’t something that was solely reserved for the villains.

Every single member of this group of immortals possess both sexual characteristics, except for the girl who allies herself with the humans. There’s no plot reason why she shouldn’t have been able to transform into a masculine character like the rest of her family when she can transform into a butterfly. It kind of sucks because it would have been nice to see a gender non-conforming character who didn’t want to wipe out the human race.

But as I watched samurai butcher their kin for the sake of preserving their clan’s honor, it was hard to look upon them as the righteous faction. The feudal Japan in the story must have been a terrible place to live. If the immortals hadn’t been led astray by their genocidal leader, then maybe the island could have truly been a paradise. If Kotaku was a hell’s paradise, then the Tokugawa Shogunate must have been a paradise’s hell.

You can read Hell’s Paradise on the official Viz website with a subscription. An anime is also slated to arrive this fall.