In 1439, a goldsmith named Johannes Gutenberg was working on an ill-begotten project to create polished metal mirrors designed to capture the holy light from religious relics, to be sold to pilgrims visiting an exhibition in Aachen, Germany. However, after flooding led to the event being delayed by a year, Gutenberg found himself out of money, and instead turned to his other project, a press that would use movable type to mechanize the process of printing books.

By 1450, in the German city of Mainz, his first printing press was built and working, and by 1455 he was printing the Gutenberg Bible. Between the 1460s and 1480s, the printing press went from a local business to something found across Germany, eventually spreading Western Europe-wide come 1500. This coincided with burgeoning religious turmoil during the rise of proto-Protestantism, the prelude to the Reformation, creating a threat to the Catholic rule with the dissemination of anti-authority publications suddenly more viable.

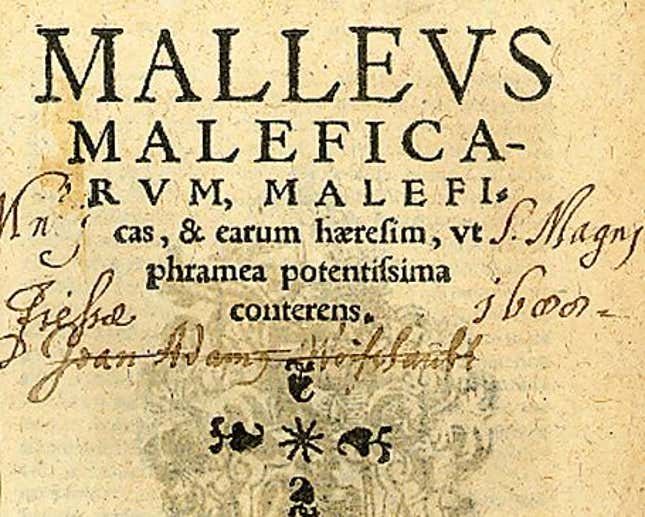

In 1486, a German Catholic clergyman and sexual pervert called Heinrich Kramer wrote a book called Malleus Maleficarum. It was a deranged and conspiratorial collection of gibberish about demons and witches, a compendium of superstitions that had built up over the last century in Europe, and a book that suggested the only solution for all of these issues was torture and murder.

A few years earlier, Malleus Maleficarum might have been copied out a few times and shared among the local clergy, and—along with Kramer’s prolific preaching—presumably inflicted a lot of harm on those in Innsbruck and the surrounding areas. But instead the book appeared at the convergence of multiple factors, given the country in which it was written, and the religious unrest that was occurring all across Europe, and the contemporaneous establishment of a means of mass-producing books. Malleus Maleficarum, thanks to this serendipitous confluence, went on to become a phenomenon, its renown spreading through the 16th century. And despite the initial cries of heresy from both within and without the Inquisition, the book ignited a widespread moral panic in both the church and the public, focusing broad fears about the dangers of witchcraft, and introducing the need to torture and kill all who were suspected.

Buried Treasure

Buried Treasure is a site that hunts for excellent unknown games that aren’t getting noticed elsewhere. You can support the project via its Patreon.

The book, of course, argued that women were far more likely to succumb to witchcraft than men, these beliefs tied up in Kramer’s sexual fetishes, and created the notion that a “witch” was more likely to be female. With 28 editions published over the next century, it became the accepted manual for dealing with this satanic plague amongst both Catholics and Protestants, riding this perfect storm of newfound accessibility, religious unrest, and the 15th century’s hurricane of superstitions.

Malleus Maleficarum would go on to lead to the torture and brutal deaths of countless women over hundreds of years: Between 1400 and 1775 (the peak being the mid-to-late 16th century), some 60,000 people were executed for witchcraft, 80 percent of whom were women.

In the short indie horror Daemonologie, you play a witch finder of the 1600s, sent to a small Scottish village to discover the identity of an alleged local witch. Only six people remain in the village, and you must speak to them all to hear their accusations and defences, and after five days, identify who should be hanged for witchcraft.

This is an astonishing game, presented in a combination of scratchy, white-on-black drawings and hauntingly brilliant stop-motion animations, and written in old Scots English. There are four days of play, in which you speak to each of the locals to hear their beliefs and protestations and, should you want to hear more information, make use of the nonchalantly included option to crudely torture them. When you’ve unearthed four new pieces of information, night falls, and you have a prophetic stop-motion nightmare to guide you in your decisions. Normal stuff.

It’s worth noting that the game begins with a message explaining that it’s intended to be played in old Scots English, and while there’s an in-game glossary if needed, it also offers a version in modern English. If English is your first language, you don’t need the latter, believe me—it’s all easily understood, or inferred, and adds a great deal to the whole atmosphere of the game.

Among the villagers, there’s Maiden Lilias, who spends her time in the Ring O Stanes, a stone circle that the local priest believes is the site at which she kills babies. She, however, maintains that she’s an herbalist, like her mother before her, at the stones to meet her lover who is missing. Then there’s Blacksmith Oswain, in the Smiths Abode, whose jaw is held on by a wire cage after what he claims was a curse by the Shepherd Violet. She instead accuses Oswain of releasing a wolf among her flock, killing her sheep and her livelihood. Accusations fly.

I wondered if it might be possible to finish the game without using the “torture” option, given that didn’t seem a comfortable pick when the other choice was “Talk.” I’m not one prone to choosing to torture, as it happens. However, it is not, and that’s rather brilliant it turns out, given the unconscionably matter-of-fact tone the witch hunter, and in turn the game, takes throughout. Tortures play out as grotesque minigames, where you pull at a person’s tongue until it tears, or time mouse clicks to squeeze a person’s fingers until they’re crushed. They’re disgusting little things, like twisted versions of a golf game’s timed swings, that may cause a character to reveal information they were holding back, or even to confess.

There’s no joy in this. But there’s no expressed revulsion, either. It’s coldly delivered by the witchfinder, albeit with accompanying screams from his victims. It matches the aesthetic decision to have the stop-motion characters all appear with blank space where their faces should be—this is a game that entirely trusts you to have appropriate reactions to unjust horror, rather than needing to demonstrate it to you.

Then, come the fifth day, you make your accusation and that person—again in the incredible, black-and-white stop-motion film—is hanged. And you leave.

This coldness is what makes Daemonologie so brilliant. It’s what makes this a 30-minute game that led me to research (read: trawl Wikipedia) and write this piece’s introduction, primarily inspired by the first episode of the BBC’s fantastic The Coming Storm podcast, to understand how humanity reached such a nonchalance in the face of such deranged cruelty.

It certainly helps that it’s wonderfully drawn, with incredibly atmospheric sound and music, coupled with every line being so meticulously underwritten. And there’s the small matter of those unnerving, sometimes horrifying stop-motion nightmares. This is all the work of one guy, Chris Evry, a passion project made in his spare time, sold for only $3.

Daemonologie achieves so much more than it otherwise might thanks to its brevity and its lack of an attempt to preach or proselytise. The horror is the horror, and it’s not a scary witch. That you have to be a part of that horror to experience it only makes it far more powerful.

Daemonologie is available on Steam for just three bucks.

.