It should be no surprise to anyone that the very mention of “trigger/content warnings” is likely to spark politically driven, reactionary rejections that whine about “snowflakes” and spoiled experiences. Years of poisoning the well in this area have made the terms frustratingly charged. But if we move on from the now-tired knee-jerk rejection of discussing content and consent in games, we can instead arrive somewhere that considers games as worthy and impactful products of art that deserve careful attention.

I recently spoke with Claris Cyarron, the co-founder and Creative Director of Silverstring Media, and Dr. Raffael Boccamazzo, Clinical Director at Take This, a nonprofit organization dedicated to helping developers navigate the nuances of mental health in video games. The two spoke at a panel at this year’s LuddoNarroCon to discuss the role of content warnings in games as well as the role of developers in telling nuanced stories. The panel, below, is well worth your time if you’re interested in the topic as it considers it from multiple angles. I was interested in following up with Cyarron and Dr. Boccamazzo to get more of a sense of the effect of content warnings in practice, as well as address concerns over content warnings giving too much of an experience away up front.

With content warnings, it so often seems that the focus is on a big, intimidating “warning in bold typeface” as Dr. Boccamazzo told me, carrying the weight of an expectation that they might somehow prevent a person experiencing a retraumatization as they play. Instead, the reality is more nuanced; this is about letting people know what to expect, and by doing so, valuing the time they’re going to spend with a game. As Dr. Boccamazzo indicated in our conversation, research into whether or not warnings actually mitigate literal trauma responses has been “kind of a mixed bag,” without showing too much of a “significant effect one way or the other.” While they may or may not be helpful in a clinical sense, there are other more down-to-earth reasons to include them, especially in offering the benefit of allowing people to have a set of reliable expectations about a forthcoming experience.

In our conversation, Boccamazzo referenced a recent study out of the University of Edinburgh that took quantitative and qualitative approaches to observe student reactions to content warnings in academic environments. The results were that only a small minority felt that being forewarned about potentially complex subjects in a class was in any sense patronizing or pointless. The majority of students had in fact responded positively to having content warnings for classes potentially covering difficult subjects.

The inclusion of content warnings wasn’t to prevent subjects from being covered, and didn’t necessitate gating off certain topics; students in the study did not express that any topics were off-limits for a class discussion.. There was instead an appreciation for a set of warnings that helped avoid surprises around sensitive topics. Though we may not have the data to suggest trigger or content warnings prevent an actual traumatic response, it is worth considering how getting a heads-up about certain content can still be beneficial. As Dr. Boccamazzo stressed, “So much of the time trauma is a forced experience.” A warning grants a person more agency to choose to engage with something.

This centered our conversation less around what we would consider a “content warning” and more on a conversation about consent, about letting a participant, or consumer, know what something is about in broad terms and then giving them the option to engage with it. Dr. Boccamazzo stated that, “If we’re giving people [the option to] consent, we don’t need to use the term trigger [or] content warnings.” There’s good reason to consider the same is likely true for trigger or content warnings ahead of playing a video game.

“Those terms have become so politicized and weaponized,” Boccamazzo added, “far away from their original intent,” so it’s important to push past this language to instead be clear about what we mean when we use them. For example, “trigger” has a very “specific [clinical] meaning and it’s not the same as discomfort.” We should be clear about what words we use, the doctor argues, and what results we’re looking for, which in this case should be about promoting awareness and consent.

How and what we “warn” people about in media, and the language we use to do so, does make a significant difference according to these experts. Cyarron framed the topic of choosing the right terms and approaches as an “ongoing process,” which should be open to player and community feedback. She also framed two distinct approaches to content warnings and discussions:

Community-led endeavors such as GamePhobias.com and Does the Dog Die, Cyarron stated, create an incredible wealth of references and resources that allow for in-depth knowledge and a “more experienced palette” over what a single dev team can do on their own. Developer solutions, however, are often far more specific to an individual game, something that’s highly dependent on “what size the team is, what type of game it is, what the point of the game is,” as well as considerations for audience, genre, and marketing goals.

Because of this, Cyarron believes that the future of content warnings–a term she stated Silverstring Media has moved away from, choosing instead to see this as “getting consumer consent” and providing “content consent features,”–is going to rely on multiple standards and approaches. It’s a “message from the devs,” she states, about what the game’s experience is going to be. As such, it’s natural to expect this to vary from game to game.

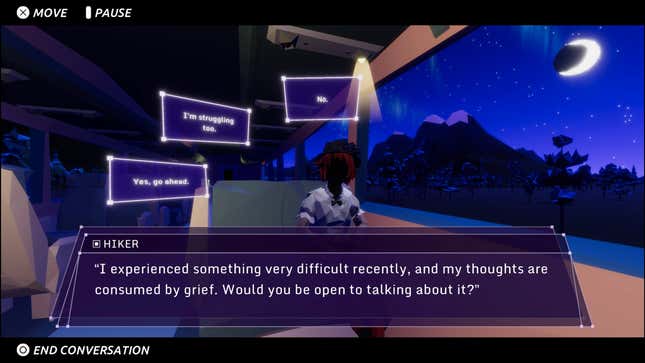

Silverstring Media’s most recent project, Glitchhikers: The Spaces Between, has direct goals. It’s a game about liminal spaces in which a player’s mind can wander and drift between topics, some of which can be painful. Cyarron said that, coming from a background in architecture, she sees games as “spaces that people inhabit.” These are virtual places where “someone is going to live some part of their life,” and as such, ought to be treated with respect and consideration for the experience.

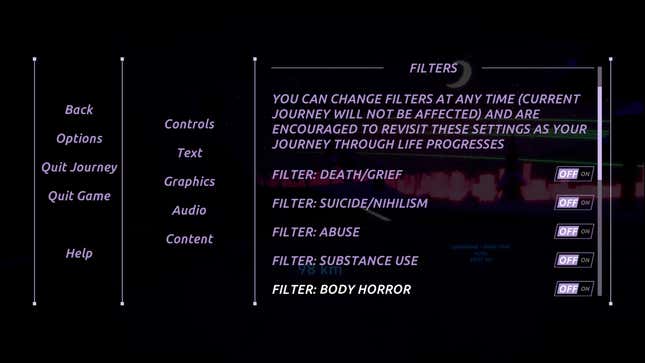

Key to Glitchhikers is the metaphor of the driver, that playing as one you are in control. Conversation options in the game allow you to engage in difficult conversations if you want, and you have the ability to, for example, ask someone to put out their cigarette or joint when they get in your car. The menu options, however, take this to an incredible degree of control, allowing you to completely turn off mentions of difficult topics that you might not desire to talk with NPCs about, or other elements that you don’t want to see, such as death, grief, suicide, substance abuse, and so on. The result is a stunning parity between the intended vision of the game and how you can actually play it.

In my own experience, Glitchhikers’ content filters enabled me to enter this game with an awareness and understanding of what topics this was going to cover. I myself have my own relationship with long-distance travel in ways that touch on some delicate subjects for me. Going into Glitchhikers, I felt informed that I was going to probably have to sit with thoughts and memories that are a bit rough, and it was liberating to know that I had control over how much of that was going to be present.

If I wanted to just check out a cool little indie game, I could do that and maybe avoid the heavy topics. If I wanted to shut the lights off and let this game guide me down perspectives on life and my own memories, I could do that too.

During our conversation there was talk about the “symbiotic relationship between developers and players.” Dr. Boccamazzo talked about Take This’ work with Double Fine’s Psychonauts 2, and how the opening statement on mental health saw fans embracing this level of communication and honesty. It was also key to Double Fine’s genuine concern over portraying these topics with compassion and sincerity, as well as providing resources for those who need them with the accompanying link.

Solutions and approaches like this speak to the power and influence AAA games can have in this area. Cyarron talked specifically about how The Last of Us 2’s accessibility features provided a template for Glitchhikers to follow. This approach isn’t prescriptive, she stresses. The route that Glitchhikers takes was the result of a decision-making process that Silverstring Media went through when considering what this game was about and who it was for. “There’s always going to be a push and pull,” she stated, but she believes that the investment of time, money, and resources in content consent features has a valuable and important role.

Considering the role of content warnings or consent features, Cyarron said, involves developers asking themselves critical questions about their game, such as: “What are the moments that you think you’re going to have in a game?”; “What role are difficult subjects going to play?”; “Are potentially traumatic scenarios life and death for certain characters?”; “Do difficult decisions lead into branching paths?” This expands to the marketing, how developers want to guide and influence the conversation and expectation about their game. “Isolating the content,” Cyarron said, is where the work begins. Pinpointing what difficult subjects are in the game is just the start of deciding how you’re going to inform your audience and what features you may include in your game to address these topics.

One of the common arguments against content warnings usually concerns how they might spoil the experience by revealing too much ahead of time. An example that comes to mind, for me, is the reveal of the Flood in 2001’s Halo: Combat Evolved. For those who aren’t familiar, I suppose a spoiler warning for a 21-year-old game is due.

The zombie-like parasitic lifeforce known as the Flood appears almost out of nowhere about three-quarters of the way through the game. Before this, the game appears to be a violent-enough romp through a space opera setting with sparkly guns and squeaky aliens. The shift to the body horror of the Flood is a sharp turn in tone that could be potentially spoiled with a content warning.

I brought this example up in my conversation with Cyarron and Dr. Boccamazzo. Cyarron reframed the impact of this particular development in the game, stressing that the real power of that scene and shift in Halo is less about just the body horror elements of the Flood and more about the change in power for the player. The majority of the game puts you up against alien forces that you’re equipped to take down enough to fulfill the “one man army” fantasy of this FPS. When the Flood arrive, however, they are so remarkably more powerful that the impact of their appearance is less about the fact that they’re a space-zombie virus.

A content warning about “body horror” wouldn’t, in fact couldn’t, spoil that narrative development. And as Cyarron told me, something like “body horror” might be expected for a first-person shooter anyway. A content warning might address the violence in the game, might help give someone a heads up that this game gets pretty gruesome and by how much, but the impact of the Flood is one that’s revealed through the narrative pacing of the game, the score, and the level design. Content warnings aren’t here to spoil the narrative beats, but they instead function, if anything, more like a movie trailer, letting you know what thrills you might be in for. Arguably, a content warning addresses this with more nuance and concern for spoilers than your standard movie or game trailer does. Trailers are often more like truncated versions of what they’re advertising.

Take, for example, recent trailers for season three of Amazon Prime’s The Boys, which directly spoil character developments. Content warnings about the visceral violence of this show wouldn’t spoil the experience in the same way as a trailer revealing which character will gain new super powers, nor indeed when and where such visceral violence may occur. That said, trailers are a perfect example of a form of expectation-setting that we already have and culturally accept. Content warnings are arguably far less intrusive and more nuanced in setting expectations.

As Dr. Boccamazzo said, “I watch movie trailers for a reason. I want to know if this is the kind of movie I want to watch.” Content warnings, or however you may choose to phrase them, allow us an informed choice. In the case of something like Glitchhikers or Psychonauts 2, this can also reveal that the content is being approached with sincerity, that the devs care about what’s in their game enough to let you know what to expect.

If we can move past the impulse to reject efforts to make gaming more inclusive and accessible for folks of different experiences, I think we open the conversation up to something more profound, one where we start talking about the actual emotional effects games have on us. Having these conversations and taking initiative to help set expectations is a process that won’t be gotten right every time. Content warnings aren’t mandates to slap boilerplate language in front of a piece of media, nor are they restrictions on stories that can be told. They’re instead an opportunity to set expectations in a way that’s arguably less revealing than a gametrailer. It’s not about placing special safety zones around difficult content, nor in any sense suggesting that certain topics, no matter how extreme, should not be covered, but rather about allowing difficult content to exist in a space where it’s treated with the respect and nuance it deserves.

Thanks to LudoNarroCon for facilitating my conversation with Claris Cyarron and Dr. Boccamazzo.