Every morning, I run a pick through my hair. It’s important that I do this when it’s still spongy and damp from the shower. Wait too long and my hair gets drier and less cooperative, making it harder to pull the comb through my natural. (Pro tip: A natural is something black folks sometimes call hair that hasn’t been altered or straightened by heat or chemicals.)

After the picking out, patting down and shaping are done, I always think to myself, “Goddamn, I love being black.”

Video games have yet to deliver the same feeling to me.

[Note: This essay, which originally appeared on Kotaku 10/14/15, is excerpted from The State of Play, an upcoming collection of writing on video game culture that came out on October 20.]

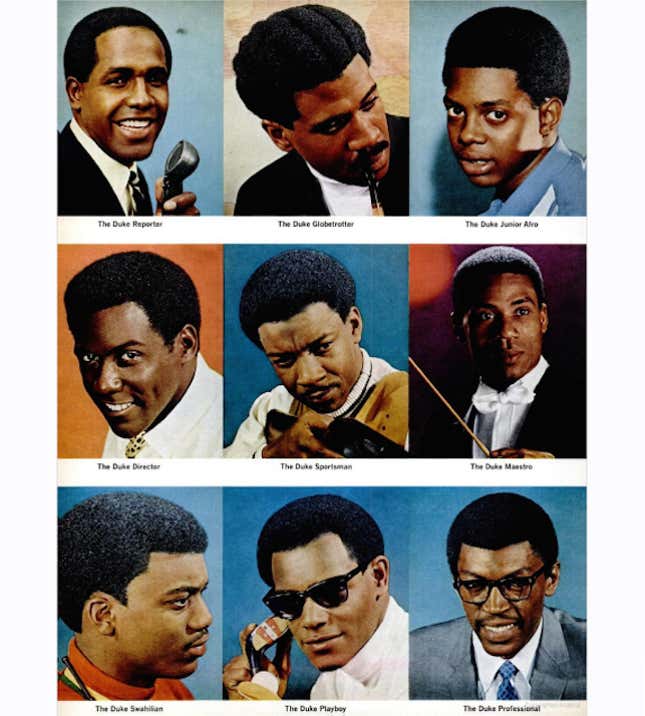

My hair doesn’t really qualify as an Afro or even a baby Afro. It’s kind of a dark taper fade, with the sides grown out a bit. It’s exactly the kind of haircut that millions of black men all over the world have been wearing for centuries. Millennia, even. And yet it remains exactly the kind of detail that the science-fiction wizardry of modern-day game-making hasn’t figured out how to replicate.

When you see the billboards and TV commercials for big-budget video games out in the world, it can feel like the designers and programmers in the games business are just a few algorithms away from breathing life into eerily accurate human avatars. The days of a neckless Mario or a Link with unarticulated fingers are long gone. Lots of modern games let you craft your own hero, opening up the rendering power of its software to the player. That’s within certain parameters, of course. When a game lets me create a character to be a protagonist, the first thing I try to do is recreate myself in digital form. It’s an uncontrollable urge, a kneejerk reflex borne from decades of never seeing enough black people—ones who weren’t tokens, punchlines or subhuman caricatures—inside the comics, TV shows, movies and, yes, video games I took in while growing up.

The create-a-character options in games like Mass Effect, Skyrim or Destiny can be marvelous things. They have on-screen tools and visual effects options that let you control how far apart your avatar’s eyes are or the length of the bridge of a nose. I can reproduce my thick lips or wide nose sometimes. A goatee? No problem. But when it comes to head hair—specifically locks that look like what grows from my scalp—I’m generally out of luck.

Not all black hairstyles are so neglected. Big, blown-out Afros or high-top fades get thrown out there from time to time, often to comedic effect. When Allen Iverson and urban gangsta flicks like Menace II Society captured the imagination of white folks worldwide, you’d see characters with cornrows or long braids in video games. Likewise, dreadlocks tend to be a staple of black video game hairstyles now. Cornrows and dreadlocks have in some things in common. They can approximate the way that white hair generally grows: down past the ears and shoulders. Hell, straight on down to the back, if the wearer feels footloose and fancy-free. But, the other thing the two styles have in common is the whiff of fad or trend. Dreadlocks and cornrows went from being controversial styles that a small segment of the population wore to ones that became more acceptable to society at large and they remain heavily exoticized.

Both inside and outside black communities, these two styles took on meanings. Inside black communities, cornrows often get worn for their ease of care and dreadlocks can be meant to symbolize religious convictions and/or ethnic pride. But outside black communities, black people wearing these styles have been subject to cultural discrimination, with schools and employers refusing to admit students or hire workers who wore them. Progressive changes in perception happened in large part because of cultural movers who wore them like Bob Marley or Allen Iverson. They gradually became part of a visual shorthand that communicated spirituality, edginess or threat. Afros were controversial once, too, but wound up taking a left turn on the path to mainstreaming. They’re now understood in a comedic way, a style so outlandish that only the truly ludicrous would wear it. It’s telling that the equivalent for straight hair—locks that go down past the shoulders, say—isn’t a signifier of imminent hijinks. So video game producers and art directors put them in their creations to draw on that shorthand. “See, our black character is spiritual. Or edgy. Or threatening. Threateningly edgy in a spiritual way. What’s that?! An Afro?! Boy, this black guy must really funny! Get ready to laugh at him, players!” Look at a natural and what do you think? “Boy, that sure is… middle of the road.”

A hairstyle like mine just grows how it grows. Sure, I get it cut a certain way. But it’s still pretty conservative. Boring. Common. Like I said before, millions of black men have been letting their hair grow like mine since time immemorial. Sidney Poitier. Morgan Freeman. Kofi Annan. Nintendo of America COO Reggie Fils-Aime. Chiwetel Ejiofor. My dad. The people making video games probably see it a few times a day, even if it’s just on TV or the internet. That’s what makes it so puzzling that a good-looking version of the basic natural has proven to be such a rare beast during my travels through hundreds of video games.

Usually, I have to settle. Resign myself to picking the black color option out of a customization palette wheel and selecting a cut that hews relatively close to the scalp. The caesar cuts of myriad video games—like George Clooney used to wear in his early days on E.R.— have become a glum safe haven for my natural aspirations. “Ok, fine,” I tell myself, “I guess I can choke this down. I always wanted to look like a Klingon from the original Star Trek episodes.” (No, not really. I haven’t wanted that look. No one ever has.) A black friend told me, “I’ve done this exact thing so many times. It’s especially a moment in online games, when I’m on a Skype call with my friends waiting for me to join them. I just sorta break down and go, ugh, fine, the caesar is close enough.” Even when I lie to myself and say that the color and density are close to acceptable, I can still see the stringy, thread-like locks fringing around the hairline. Nope. Not black hair. At least, it’s not my black hair.

It’s the visual texture that’s the trickiest part, I’d imagine. From afar, hair like mine looks like a solid, unified dome. But, it’s actually a particulate mass, made of hyper-tight curls that pretty much resist gravity by growing up and out. There’s a chunk on the left side of my head that grows faster and thicker than the right side. I’ve got to pat it down more. Sometimes, it sticks out more stubbornly and destroys any fantasies I have of rocking a symmetrical ebony corona. In photographs with strong lighting, you can make out the wooly piles of waves where the uniformity has broken back down into unruly almost-tendrils. I understand the challenge in recreating this tonsorial paradox—unified yet individuated, cottony yet coarse—in the virtual visuals of video games.

So, what then? What will it take to perfect the video game natural? Better processing chips for the graphics cards living inside the computers and game consoles? Bleeding-edge software engines to create the digital worlds and individuals of future games? Both of those inevitabilities would be good starts. But, honestly, that stuff already happens on a cyclical basis. Computing power and coding prowess march along in lockstep with each other, destined to further enable the imaginations of the people using them. It’s the human imagination that’s the game-maker’s most important tool. And that’s why the birth of the one true video game natural needs one thing. There needs to be more black people making video games.

Any conversation about black hair is, at its root, about more than the follicles growing on a given body. These talks are really about the intersection of personal choice and inherited standards, the crossroads where a body decides what products and treatments they’re going to use to give their hair a certain look. Video games also get their steam from the friction generated at that crossroads. People who choose to make games or identify as gamers have historically rubbed up against cultural snobbery and moral panics, the result of standards that dismiss games as mere commerce. Activists like disbarred anti-gaming gadfly lawyer Jack Thompson or disgraced California lawmaker Leland Yee tried to influence popular opinion and jurisprudence in ways that essentially would have had games treated as radioactive, world-destroying material. Mainstream media reports about “violent video games” whip the non-playing public into a frenzy about the evils that video games might be wreaking on our minds. (You, dear reader, might even be one of those snobs or panickers!) So it makes sense that video game creators and enthusiasts like to trumpet their favorite medium’s accomplishments. Some cheerleaders will sing hosannas for the groundbreaking nature of digital interactivity, the core difference that generates a sense of immersion that makes games different from movies or books. Others will invoke a record-breaking 24-hour sales number like the kind notched by Grand Theft Auto V or Call of Duty: Ghosts as a sign that video games are equivalent to or better than the other media they out-earn. Video games are a smart, forward-looking artform, some triumphalists say, one that will use that seductive interactivity to absorb, re-present and re-contextualize all that has come before it. Resistance is futile, non-players. But bring up the medium’s shortcomings and you often get flustered defensiveness in response. One of those shortcomings is in the lack of diversity of the people making and portrayed in video games.

The modern era of video games—let’s call it the last twenty or so years—has barely seen any black lead characters in big-budget or independent small-team video games. Oh, there’ve been sidekicks and boon companions aplenty. Too many of those have relied on tropes and stereotypes that are embarrassingly retrograde. There’s been Dead Island’s Sam B., a street-tough, one-hit-wonder rapper whose single was “Who Do You Voodoo, Bitch.” Deus Ex: Human Revolution had Letitia, an indigent woman on the streets of a dystopian sci-fi future Detroit who somehow sounded like she came off the set of cheesy 1970s cop drama Starsky & Hutch. And a whole parade of hot-tempered brawn-centric bruisers and slangtastic slicksters have appeared in fighting game series like Street Fighter and King of Fighters, with names like Heavy D!, TJ Combo and Dee Jay, all clearly meant to convey a ‘hip’ urban lifestyle in the broadest of strokes. And there’ve been dozens, maybe hundreds of other lesser lights (lesser darknesses?) in the deluge of store-bought and digitally downloaded games. Men assembled in thrall to “gritty” hollow machismo. Women constructed to deliver trite sass or lurid titillation. Each one of them burdened with the weight of expectations they can’t possibly fulfill, because for every character like them, thousands of non-black characters get more spotlight and more chance for nuance.

But games where the main guy or gal—the buck-stops-here character entrusted with anchoring empathy, narrative and design ambition—is a black person? All too few. My quest to find and wear the natural I want might not be quite as quixotic, especially if it already existed in games with set protagonists first. Mind you, there has been fitful progress in the last few years. In particular, the Assassin’s Creed series from French publisher Ubisoft have found intriguing story and gameplay ideas in the ways that black people have defied oppressive systems throughout history. The main conceit of the Assassin’s Creed games is that they send players to sumptuously recreated cities of centuries past, plopping them in pivotal moments like the Crusades or the Renaissance and letting them encounter luminaries like Leonardo DaVinci. Amidst free-running acrobatics, lurking-in-shadows stealth and swordplay+gunplay combat, the games in the series have had aspirations of imparting a sense of the political and cultural upheaval of the time periods they’re set in.

Ubisoft has released two Assassin’s Creed games with black lead characters set during the height of the 18th Century transatlantic slave trade. Assassin’s Creed Liberation featured Aveline de Granpre, a bi-racial heroine whose French father once owned her black mother. Set in the New Orleans of 1768, Aveline’s adventures find her investigating the whereabouts of vanished slaves and searching for her own long-lost mother Jeanne. The character’s special abilities let her don three separate guises, each with its own strengths. As a high-society Lady, she can bribe officials for access to closed-off areas. She can cause riots while wearing the tattered rags of the Slave. Her other persona of the Assassin lets her do much of what other lead characters in the series can do, like killing with a hidden blade and using pistols. This game mechanic of switching roles plays off of her bi-racial background, all in the midst of a game set during a time when black people were little more than property. She’s of two worlds and has abilities that let her move through them.

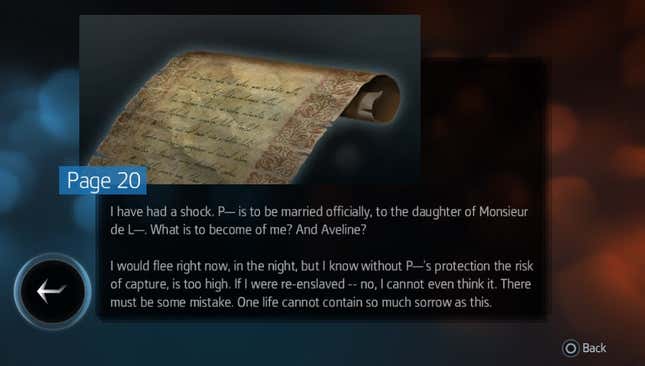

Players can discover pages from Aveline’s mother’s diary in Liberation. As you collect them, you see her command of the written word increase as she learns to read and write in secret defiance of the real-life laws that denied slaves the power of literacy. Collectible items like this are a well-trod element in many video games but the historical insight woven into the mechanic here creates unexpected poignancy. You don’t see it happen but reading these pages lets players feel Jeanne transform from someone else’s property into her own person.

More than a year after Liberation’s release, Assassin’s Creed: Freedom Cry came out as downloadable add-on for Assassin’s Creed IV: Black Flag. The main game featured pirate hero Edward Kenway, seeking his fortune while dodging the armadas of the French, Spanish and British. His first mate Adewale was a former slave who kept Kenway’s crew in line and his vessel seaworthy. The Freedom Cry add-on focused on Adewale decades after his time with Kenway, with a ship and crew of his own.

Adewale’s time on the roiling seas of the Caribbean wasn’t about getting rich, though. After a fateful ship battle leaves him stranded on Saint-Domingue—the island that’s home to the countries now known as Haiti and the Dominican Republic—players controlled him as he sought to liberate slaves and help foment uprisings. I’m a Haitian-American child of immigrants and, personally, Freedom Cry felt like a deeply resonant fictionalization of the history my ancestors came from. Hearing passers-by discuss the sub-humanity of the slaves doing backbreaking labor and giving chase to the slave catchers pursuing runaways trying to escape to freedom gave me motivations I never had before in playing video games. One of Freedom Cry’s last sections takes place in a sinking slave ship, with Adewale trying to escape a watery grave. All the while, you’re surrounded by hundreds of kidnapped Africans you know you won’t be able to save.

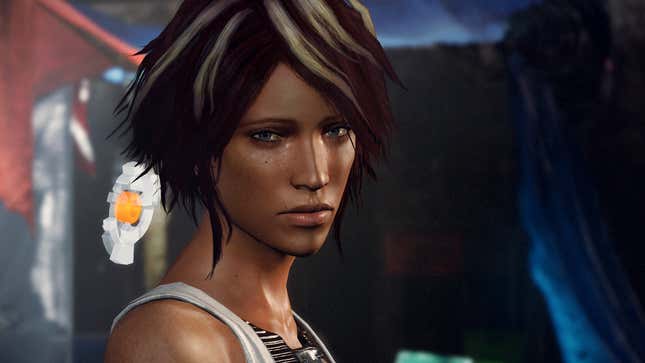

Those Assassin’s Creed games have tapped into the historical circumstances of black people in the Western world for inspiration. But another recent game did none of that and still delivered an interesting character. Remember Me, a sci-fi video game, is like hit British television cop drama Luther: meaningful because it’s not a protest document centered on race. The blackness of their lead characters is incidental and they don’t serve as signifiers for any attitudes in their fictional universes. Detective Chief Inspector Luther isn’t tortured because of racism; he’s tortured because he walks the line between legal punishment of serial killer horrors and the temptation of outside-the-law vengeance. In Remember Me, Nilin is a memory hunter, a special operative who invades the psyches of targets to reshape or eliminate remembrances. She doesn’t manipulate people’s memories because she’s descended from a people who’ve suffered horrific erasures. Her motivations for being a memory hunter come from her family history, not her racial background. Yet, by their mere presence and well-executed dramatic arcs, she and John Luther make for strong evolutionary leaps in their respective media.

Lee Everett doesn’t have a great natural. You can tell that he’s supposed to but it…it’s just not right. Nevertheless, the lead character of the first season of a series of games based on The Walking Dead is one of the best black personas ever created for a game. Though he’s an escaped ex-con, his soulful regret and concern for a little girl named Clementine humanize him out of the bounds of any facile stereotype. He’s not quick to violence or emotionally inarticulate. Indeed, the very nature of the game has players steering Lee through an uneasy leadership of zombie apocalypse survivors with agonizing life-or-death decisions at every turn. He is more empathetic and well-rounded than most other game protagonists, whether black or white. He never feels like an exoticized curiosity. With a few horrifically bad decisions and waves of undead swarming all over me, he feels like someone I could be.

In the Assassin’s Creed games, Aveline and Adewale’s motivations come in direct response to historical racial oppressions they lived under. Luther and Nilin represent another strategy of creating a black character for popular consumption, where race never gets explicitly addressed. They’re black but not centered by any definition of blackness. The strategy is more subtle in Lee Everett’s particular character construction in The Walking Dead. The institutions that doled out prejudice have largely crumbled in the game’s undead-infested world but Lee is still written in the context of blackness in the American south. The game’s characters mostly hail from Atlanta and Lee engages with folks who have different sorts of beliefs about him because of his blackness. Fellow survivor Kenny thinks that he can pick locks “because he’s urban.” Another character distrusts Lee’s potential romantic involvement with his daughter. It’s never explicitly tied to race, but the echoes of interracial romance dramas like Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner can still be felt in these scenes. And then there’s the question of Lee’s young charge Clementine. They’re both brown, which leaves some folks unable to tell if they’re biologically related or not, regardless of whether they actually look like father and daughter.

The most hopeful thing about Lee, Nilin, Aveline and Adewale is that they all come across as different from each other and from what’s come before. If video games are really to be the prime creative vessel of the coming century, then there should be room for blackness—or, more aptly, the myriad forms of it—inside of the medium. Not just the haircuts or poses that communicate a fascination with the Other—”Let’s spice up our game with a brown-colored person!”—but ones that reflect an understanding of what it’s like to be a regular black person. It’s reasonable to want more of each strategy mentioned above: games that directly address race as central (like the Assassin’s Creed ones do), games which treat race as purely aesthetic (or at least don’t address it in the text, allowing audiences to draw their own conclusions, like Luther & Remember Me), and games that address race, but don’t make it central, like Walking Dead). This is how the skeleton of a continuum of portrayals get built. Right now, there’s a clavicle and a tailbone, maybe, but nothing capable of supporting much weight.

A few years ago, I wrote an article about my frustrations. I called it “Come On, Video Games, Let’s See Some Black People I’m Not Embarrassed By” and the main thesis was about how the medium needs to tap into the phenomenon of black cool. This is part of what I wrote:

“What I want, basically, is Black Cool. It’s a kind of cool that improvises around all the random stereotypes and facile understandings of black people that have accrued over centuries and subverts them. Black Cool says “I know what you might think about me, but I’m going to flip it.” Dave Chappelle’s comedy is Black Cool. Donald Glover is Black Cool. Aisha Tyler is Black Cool. Marvel Comics’s Black Panther character is Black Cool. Their creativity is the energy I want video games to tap into.”

And more:

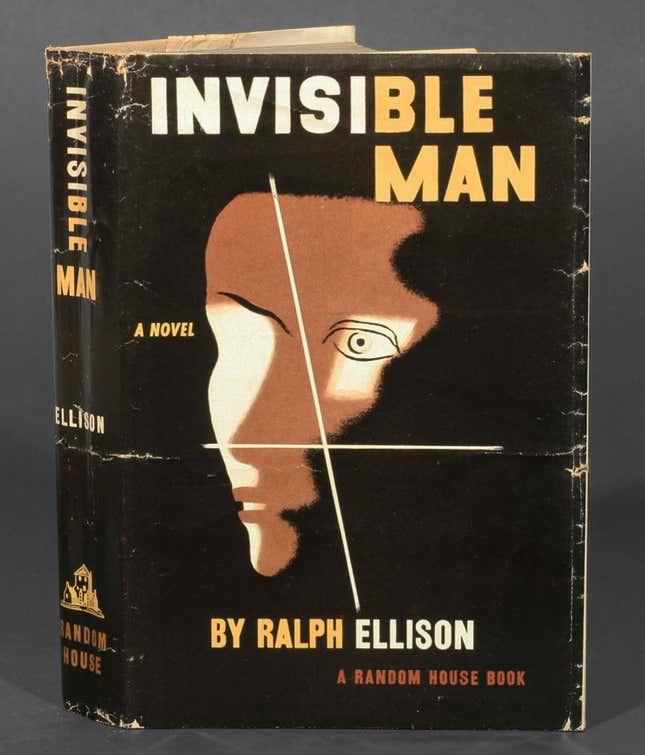

“In other mediums and creative pursuits, there’ve been the black people who pivoted the conversations, expanded the possibilities and deepened the portrayals about what black people are. In jazz, it was Charlie Parker. In literature, it was Ralph Ellison. In comics, I’d argue that it was Christopher Priest, followed by Dwayne McDuffie. For me, the work of the deceased McDuffie managed to create characters that communicated an easily approachable vein of black cool.

Video games need this kind of paradigm-shifting figure. Not an exec, mind you—sorry, Reggie—but a creative face who steers the ethos of a game. For example, you know what kind of game a Warren Spector or a Jenova Chen is going to deliver. With Spector, it’s a game that’ll spawn consequences from player action. With Chen, you’ll get experiences that try to expand the emotional palette of the video game medium. I want someone to carry that flag for blackness, to tap into it as a well of ideas.”

Since then, I occasionally get responses from people who’ve read the article, asking if such-and-such character from Video Game X passes muster. “He’s not so bad,” the yearning goes. But there’s an addendum I haven’t written for that years-old essay, which is that black cool isn’t enough.

Black Cool isn’t an end, understand; it’s a means to one. It’s a coping mechanism for existing in a world that’s denigrated and dehumanized you. It’s a way to freeze off the small slights and mega-disenfranchisements. You can break them off to keep on keeping on but doing so still breaks off a little flesh with it, like freezing off a wart.

Black Cool is a response to being denied a more complete humanity. “Choose not to acknowledge me in my fullness?,” it says, “Then all you get is the chill.” The thing that too often goes unsaid is that Black Cool is cold comfort for the practitioner, too. It doesn’t make up for lost opportunities. If you’re cool and broke, you’re still broke. If you’re cool and two-dimensional, you’re just a different kind of caricature.

For all the progress of late, I’ve grown tired of playing video games with black characters that feel they were brokered into existence. My eyes can pick out the seams of compromise as I play through them: the not-good-enough hair, the broken speech patterns, the trope-laden backstories.

I’ve heard firsthand from both black and white video game designers who’ve had to walk their corporate employers back from the cliff’s edge of truly rank embarrassment when it comes to crafting tertiary characters of African descent. I’ve also indirectly heard stories of black marketing and public relations representatives who tried to warn their higher-ups that the games they were pushing out the door had discomfiting echoes of centuries-old propaganda that portrayed black people as subhuman. Those games went out unchanged. In each case, the black folk involved weren’t high enough on the ladder to command the requisite levels of control needed to make substantive changes.

Even black-protagonist video games that I like have their flaws. In Freedom Cry, there was the messy stumble where the game’s mechanics turned the same slaves you fought to free into currency to get more deadly weapons. It was essentially something like “Liberate 300 more slaves to get access to this cool machete.” Wait, isn’t that the same commoditization that I just worked to end inside the game’s narrative? I played through that and wondered if that blunder would have happened if a majority of the people who worked on the game were black or from other people-of-color backgrounds.

When I think about what excites me about video games and what excites me most about being black, it doesn’t seem like such a weird impossibility that the two should intersect. What excites me about video games—at their best anyway— is when the conglomeration of mechanical systems, music and art congeal into result that’s capable of being deeply expressive about the human experience. A video game like Jason Rohrer’s Passage can make me melancholy about my own mortality. Brothers: A Tale of Two Sons—made by filmmaker Josef Fares and game development studio Starbreeze—is a playable fable about the strengths we get from siblings, life partners or other meaningful relationships.

What excites me about being black is being connected to a history of resistance, innovation and improvisation, a history extruded out from under the most inhumane physical, psychological and systemic oppressions in human history. Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Man is only trenchant, angry and darkly funny because it rebelliously gives voice to an existence that defied all the forces that tried to suppress it. Of course, I don’t have to live inside any of that understanding if I don’t want. I can take from it as I want or need to. Canadian poet Dionne Brand once remarked that “To live in the Black diaspora is I think to live as a fiction—a creation of empires, & also self-creation.”

Yes, the empires of the video game landscape—big publishers like EA, Ubisoft and Activision—are making their slow, stumbly tentative progress. But it’s really the self-creation of black video game characters and universes that I hold out the most hope for.

When I initiated a series of back-and-forth letters about black people and video games on Kotaku, my correspondent David Brothers and I talked about Blazing Saddles, the classically impolite cowboy comedy by Mel Brooks about a black sheriff in the Old West. An embrace of satire would help game makers work touchy subjects like race into their games, I argued:

“…People don’t want to be taken the wrong way, especially if they want to make games that somehow touch on race.

That’s why satire—and its ability to lower defense with laughter—seems like a much more attractive option. What I really want is a video game equivalent to Blazing Saddles. Mel Brooks’ classic Western comedy homes in on the anxieties of its time—a post-segregation moment when black and white people are still warily integrating in various social spheres—to fuel its jokes. There are tropes in black arts traditions that game designers can use, too. The film’s sheriff, played by Cleavon Little has a bit of the trickster in him; he reorders society by going against the grain. The whole movie runs up and tongue-kisses every stereotype it can find. It’s entirely possible that people watching can use them to reinforce really nasty world views but that’s clearly not the film’s aim.

And, yeah, Blazing Saddles is absurd slapstick. But so is the root of most prejudices, right?

I want a game that pokes fun at the fact that 99.9% of game protagonists look like cousins. I want a game that clowns the thinking that noble savages are still a good plot point in 2012. I want a game that doesn’t feel the need to turn its black characters into thuggish stereotypes just because it’s an easy shorthand for being a bad-ass.”

Brothers responded:

“Here’s something else to think about: You mention Blazing Saddles being a good goal for games. I agree, and would actually include Friday, the near-perfect 1995 film starring Ice Cube and Chris Tucker, in that category. But Blazing Saddles had Cleavon Little in front of the camera, Richard Pryor on the script, and a booming black presence in Hollywood to balance it out. Friday had black culture exploding into the mainstream, rap beginning the process of absorbing every other genre, and a string of realistic black condition-type movies like Rosewood, New Jack City, Boyz n the Hood, and Menace II Society to play off of. If you weren’t into Blazing Saddles or Friday, if they offended you or just weren’t your bag, you could easily find an alternative.”

In video games, those alternatives are almost non-existent. New York City-based game designer Shawn Allen turned to Kickstarter to crowdfund Treachery in Beatdown City, a throwback action game happening in a rapidly gentrifying analogue to Manhattan. The game features a multi-racial trio of heroes and a unique blend of strategy and virtual fisticuffs. It’s the sense that this in-development game—whether good or bad—will be the product of the undiluted vision of Allen and his co-creators. The fact that you’re beating up wave after wave of thugs to save a black President? That’s his decision. Same for the music, art style and side stories that the game will have. This isn’t a game that will have been focus-tested into blandness.

However, while I’m champing at the bit for a black grassroots sensibility to spontaneously generate in video games, I’m also conflicted that it will ever come about. In my worst moments, I’m actually quite pessimistic that video games will ever experience the emergence of a Black Arts movement analogue. Structurally, it seems like the elements that allowed writers, filmmakers, playwrights and poets to organize around a desire to their own black histories, comedies and tragedies won’t ever congeal in a similar way for video games. The small-team/indie stratum of modern game-making is one of the most exciting sectors of the medium right now. Huge swells of support surround the creators trying to bootstrap or crowdfund their visions into being. But the number of black people in those circles is minimal.

The mix of patronage, mentorship and wanton risk-taking doesn’t feel manifest in video game creation right now. Leaving aside any questions about personal and individual courage, the most blatant reality is that diversifying the pool of people who star in and make games is too big a distraction. The profit margins are so thin, the struggle for relevance so fraught that it feels like most captains of industry are constantly trying not to run their vessels aground. So, the pipelines that feed talent into the game-making ecosystem—where, as elsewhere, people hire in their own image and based on social proximity—seem fated to remain homogenous. The would-be black creators never start out paying dues in corporate careers that they would then leave to go indie and create more personal visions.

And, if we’re honest, there was an element of ego-stroking cultural tourism motivating some of the non-black people who championed black creators in previous decades where institutional racism stymied entrée to creative professions. I’m talking about people like Carl Van Vechten, the white writer who helped black authors like Langston Hughes get their work put out by big publishing houses during the Harlem Renaissance. “Look, Beauregard, not only did I venture forth into Deepest Darkest, but I’ve returned with one that can actually write!” It seems exploitative in hindsight but that kind of relationship still opened doors that would be closed otherwise. Let’s compare it to the world of film. Before, say, Spike Lee directed his first big feature film, some film professor of his had to believe in him enough or be egotistical enough to introduce him to the people who’d eventually put him in the director’s chair. Even that tortured dynamic seems to be missing from the video game business.

Part of it is because there’s a stripe of player and creator who want games to be apolitical and ahistorical. They don’t understand why it’s important that my particular kind of black hair is pretty much missing from video games. We’re living in a post-racial meritocracy, right?

If we were really post-racial, then putting a black lead character in a game wouldn’t matter, right? Nary a second thought would be given. But every time the issue comes up, an ugly response meets it. I work in a position that lets me see these responses up close, and there’s nothing post-racial about them. They’re filled with a dismissiveness about the past injustices that black people have borne. “That stuff is in the past, black people. Quit your complaining and make your own video games.” Comedian Louis CK famously took out that mode of thinking on an episode of The Tonight Show With Jay Leno, saying: “Every year, white people add a hundred years to how long ago slavery was. I’ve heard educated white people say that slavery was 400 years ago. No it very wasn’t. It was a 140 years ago. That’s two 70 year old ladies living and dying back to back. That’s how recently you could buy a guy.”

Institutional racism doesn’t fall away that quickly and neither does its various consequences and implements, especially when candid discussion about any of those things is so sparse. It’s not as easy as that trollish retort would make it seem. Video games, like all pop culture, exist in an ecosystem. It’s a web of interconnected entities that are constantly trying to harness ideas, manpower and energy for creative and competitive advantage. And, still, the huge untapped black audience ready to see and create themselves in today’s games remain an invisible elephant in corporate boardrooms.

Look, I don’t like Tyler Perry’s movies. But I’m not so blind as to not see that Perry’s work as a producer/director/actor succeeds because he’s able to give a starving audience images of themselves. Not as growly fetish objects, but as hard-working, church-going everyfolk. You never have to worry about the one black guy in his movies being less than upstanding, because it’s never just one black guy. A Tyler Perry movie will have enough black women in it for him to sprinkle different personality traits around. His power and influence come as a result of the simplest supply/demand/power-in-numbers arithmetic in the world. But, somehow, that math does not compute to the movers and shakers in the video game business. They’ll go with what looks exotic and foreign vis-à-vis their construction of black characters in games, ignorant all the while of the fact that their potential black audience can see the chicanery from miles away.

In the real world, I tried to rock a different look for a while. My flirtation with a bald head came in college. The rap group Onyx, made up of a cluster of rowdy, hyperactive rappers, was enjoying its short window of popularity then. Me and a crew of friends emulated their clean-shaven pates when “Slam” was all over the airwaves. But putting my scalp on display fell away after a few months. In that particular moment, rocking a baldie may have been what was deemed cool but, deep down, it didn’t feel like me. After all, what was it that countered the self-consciousness I had throughout the years about my narrow oval head shape and ears that stuck out wide? What was it that the white boys in my Catholic high school tried to insult without ever understanding, in the showers after gym class? It was my natural.

Call it self-indulgent but I’ve come to believe that maintaining a natural is a work of art. Sometimes, I compare combing and shaping my hair to sculpting clay. The most important part happens when it’s wet, but the shape it takes when dry is all people will see during the course of a given day. I wonder what I keep doing it all for, too. My hairline’s receded a damnable amount and there’s only so much longer that I’ll be able to hide the thinning patches at the top of my head. But, for now, I’m not going to shave it all off. I’m going to keep maintaining my natural, in the probably delusional hope that video game creators large and small will learn how to import it—and the humanity lived by people who wear it—into their works.

illustration by Jim Cooke.

Contact the author at evan@kotaku.com.