In the wake of the international success of Persona 5 and Dragon Quest XI, perhaps it’s time for publishers to take a look at some of their long-dormant JRPG series. Capcom’s Breath of Fire, which is packed with strong ideas and still in the hands of a financially healthy publisher, is the perfect place to start.

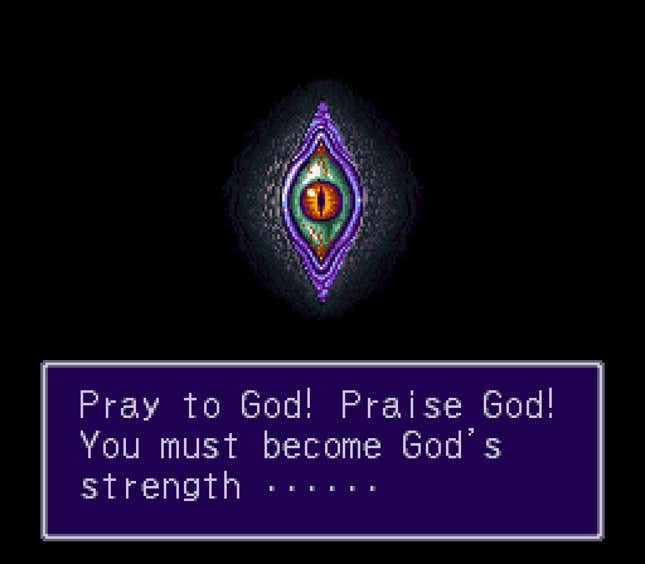

In December, Nintendo updated the Super Nintendo library for its Nintendo Switch Online service to include a few new games. Among them was Breath of Fire II, a Japanese role-playing game from 1995 that opens with an image of a dragon’s eyeball imploring you to become god’s strength.

Breath of Fire II is full of more deliciously weird moments like this, and it’s solidly designed, but it’s legacy isn’t as strong as other JRPGs on the system like Final Fantasy VI or EarthBound. You could say the same about the whole Breath of Fire series: It was always fascinating, but never quite felt essential. Just as the series began to find a more unique voice by daring to lean into pricklier roguelite mechanics with 2003’s Breath of Fire V: Dragon Quarter, it went silent.

It wasn’t the only one. In the 90s, JRPGs were vast in number and varied in concept. It helped that games were cheaper and quicker to produce. Over the last two decades, as development costs have risen, lots of smaller Japanese studios closed or were bought out. A few major players kept JRPGs alive by embracing a model of large, mechanically conservative entries every few years.

There are still new ideas. I love the way indies like Undertale, Indivisible, and CrossCode have kept the innovative spirit of the genre alive, but they lack the sheer spectacle that bigger budgets and studios can provide. The days when a JRPG would regularly contain both extravagance and experimentation in one game are likely gone for good.

Breath of Fire is the series that could bridge the gap. To be honest, I’d rather have other classic franchises like Suikoden or Lufia return. But, almost all of those classics were made by studios that are currently either asleep or dead. Breath of Fire is one of the only dormant JRPG franchises left in the hands of an active, profitable company. Capcom’s recent successes should mean they have capital and reputation to spare. They should spend some of it doing something big and weird, like resurrecting Breath of Fire.

I understand it may seem cynical or myopic to argue that we in any way need the critical middle child of JRPGs to return. Yet, Breath of Fire’s average reputation belies its colorful, varied approach to the genre.

The SNES entries, 1994’s Breath of Fire and 1995’s Breath of Fire II, show that the series always had a grasp on the lively world and feeling of adventure so key to the genre. These games are from the JRPG-as-anime style of design, where you get to know a core cast over a series of trials and adventures. They do live in the inescapable shadow of Final Fantasy and Dragon Quest, but they aim to build on that legacy by painting a new vision in technicolor. The first game lacks polish, but the second’s goofy, dark world and vibrant cast really shine—if you ignore the notoriously terrible localization. The second game also steps up the quality of animation, often looking every bit as gorgeous as some of the best games on the SNES. The focus on visual quality is a trend that continued through the rest of the series.

The series made the jump to PlayStation with 1997’s Breath of Fire III. It’s an energetic game, full of gorgeous 2D pixel animation in a 3D world. It’s ambitious—to a fault. It can’t present its new ideas cleanly enough, or get far enough away from frustrating old ones (Iike the interminable encounter rate common in older JRPGs), to coalesce into the classic it so clearly wants to be.

It wouldn’t be until 2000’s Breath of Fire IV, also on the PlayStation 1, that the series would find that correct blend of all its strengths so far. It’s a rock-solid RPG and the most gorgeous in the series, pushing the PlayStation to its limits to create characters as evocative and meticulously animated as those of Capcom’s fighting games. The moody, contemplative narrative, boosted by finally receiving a decent localization, explores the personal and national consequences of war and introduces more Eastern mythological influences to the lore. It’s the ultimate realization of the series’ traditionalist ambitions.

This is what makes 2003’s Breath of Fire: Dragon Quarter, the series’ only PlayStation 2 entry, such an exciting heel turn. It shifts the setting to a post-apocalyptic underground society with a deep class divide where the sky itself is treated as myth. In Dragon Quarter, every normal JRPG system is tuned like a survival horror game to highlight the desperation of your climb to the surface. Failure is not only an option, it’s expected: You’re meant to start the game over from the beginning, with your accumulated items and character progress intact, multiple times before you can become powerful enough to finish it. Dragon Quarter was a clever twist on the JRPG formula that pointed to an intriguing future for the series, but it turned out to be its death knell.

No other Breath of Fire games were released until 2013, when Capcom released Breath of Fire VI. Unfortunately, it was a free-to-play online multiplayer game for PC and mobile that never left Japan. Videos of gameplay indicate that it’s the worst version of what you’d expect, microtransactions and all, when an established series goes free-to-play. It garnered an extremely low average rating of 1.5 out of 5 on the Google Play Store and shut down permanently in 2017, about a year and a half after release.

That shouldn’t be where Breath of Fire ends. Capcom recently figured out how to get Monster Hunter’s formula in front of a wide audience, and resurrected Resident Evil from action-movie hell, so it’s not out of the question that it could do the same by locating Breath of Fire’s core strengths. Dragon Quarter’s mechanics were read as hostile by players at the time, but in a post-Souls world where Darkest Dungeon’s brutal combat thrives, those same decisions would seem brilliant. The recent success of Octopath Traveler proves there’s an appetite for older JRPG systems, and the type of 3D-2D visual synthesis that Breath of Fire IV refined. The series’ thematic focus—on the fallout from war, distrust of authority, and how those living in the center of the consequences attempt to correct the sins of the past—certainly hasn’t gone out of style.

I know it’s a longshot. I know that if it were possible to write about a dragon-focused Capcom game enough that a new one would magically appear, we’d have several more Dragon’s Dogma games. Still, I can’t help myself. I’m calling for another resurrection in this era of remakes and reboots, but not because I just so desperately need the dead to live again. It’s because I see something that used to spark, and I think it could still become a fire.

Ben Morgan is a freelance writer and game designer living in Portland, OR. He loves cats, JRPGs, and movies where Michelle Yeoh kicks ass. You can find him on Twitter @benji_ray.