The decade is coming to a close, year and years of forward progress in design and production having transformed games as we know them. Professional actors fill video game casts and look so realistic that they might as well be right there. It’s a remarkable change, but I’ve gotta say, I miss the hammy voice acting of old Japanese role-playing games.

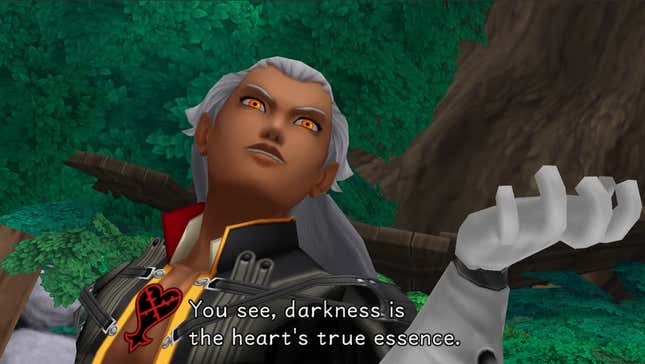

Take Kingdom Hearts, for example. The original game, released in 2002, was a mishmash of established voice actors and a celebrity-laden cast that didn’t always feel up to the task. Some of the decisions were baffling, and most were recast in later games. David Boreanaz made for a stilted and odd Squall Leonheart. Mandy Moore had some quiet charm as Aerith but there was a sense that her lore-laden lines prevented her from offering a stronger performance. Hell, Lance Bass from NSYNC cameoed as Final Fantasy VII’s villain Sephiroth! One voice stood above them all: BIlly Zane, known for films like Titanic and The Phantom, played the villainous Ansem and damn he was amazing.

Zane’s performance is a combination of rocky growlings and deep bass utterances. He chews scenery into dust, spits it back out, and chews again. Ansem is intimidating, excessive, and absolutely dangerous. No one talks like this, save for the mad villain who yearns to bring darkness to all worlds. In isolation, it’s silly. In context, it is terrifying. Kingdom Hearts is a broad game about good and evil; for its sweeping story to make sense it requires grand villains.

This has been the case, particularly in role-playing games, for a long time. There’s a lineage of hammy overlords that, almost excessive by today’s standards, breathe considerable life into simple stories of good and evil. Realism is often compelling, too. Seeing Joel and Ellie believably react to horrible situations and people in The Last of Us can be gut-wrenching. But there’s something to be said for excess. For the moments a villain flicks their cape and laughs maliciously.

Cliche villainy can be a hallmark of a genre or even a game-defining performance if done well. Among the best examples is John Truitt’s turn as the scheming Lord Ghaleon in Lunar: Silver Star Story Complete. Released on the PlayStation in 1998, Lunar was a remake of a classic Saturn game. Its North American publisher Working Designs is best remembered for the intricate packages that games would come in, but they also incorporated voice acting into their remakes. Truitt plays Ghaleon with a sort of fey indifference before turning truly pompous once revealed, midway through the story, to be the game’s villain. It’s not good acting by today’s standards but it works for the game. It also works for a JRPG, tapping into a wider lineage of television and even stage performance that can often be found in their romantic narratives.

Even today, the occasional video game acknowledges that villainous performances deserve a certain level of harm. They require a clumsy but cheesy sense of self or else they lose their identity. Resident Evil would not be the same without D. C. Douglas’ strangely staccato take on Albert Wesker. Final Fantasy XIV villain Emet-Selch would be less endearing without René Zagger’s theatrical twists and turns. Even Red Dead Redemption 2, a watershed moment for realistic visuals and performances, would lose something if not for Benjamin Byron Davis’ caterwauling turn as Dutch Van der Linde.

These performances come in bursts, covering our increasingly photoreal world with a happy helping of cheese. In the best cases, they continue a tradition of bombastic theatrical performances, rounding out a genre to its best possible form. Horror, adventure. Like stories told by a campfire, they’re sometimes best with silly voices and too much effort.

All of this is a long way of saying: Wow, I wish Billy Zane had been in the other Kingdom Hearts games.