Tetsuya Takahashi has a story to tell.

It began in 1998, with the release of Xenogears. It began in 2002, with the release of Xenosaga Episode I. It began in 2010, with the release of Xenoblade Chronicles. It ended in 2022, with the release of Xenoblade Chronicles 3.

In all likelihood, it will begin again. Takahashi, like so many artists, compulsively retreads the same ground in nearly everything he creates, and there’s no reason to suspect Xenoblade 3 will be his last project. But the game nevertheless represents a major milestone in the director’s decades-long career—the first time one of his outsized, idiosyncratic, multi-game sci-fi RPG projects was fully realized and brought to its natural, intended conclusion. That’s not just speculation: in a statement made shortly after the game’s release, Takahashi personally described Xenoblade 3 as the end of the overarching narrative that began with the original Xenoblade Chronicles. The series may very well continue, he says, but this particular arc will not.

Crucially, in this same statement, he refers to Xenoblade 3 as a “culmination.” In context, this can be taken to mean a culmination of the ideas and mechanics conceived in Xenoblade and Xenoblade 2, but I see Xenoblade 3 as something much grander. I suspect he does, too.

Read More: From Xenogears To Xenoblade: The History Of Monolith Soft

Every game Takahashi directs for the remainder of his career will inevitably be compared to Xenogears. Chalk this up to a few factors. The first, and most obvious, is that he can’t stop remaking it. Though the 1998 PlayStation game never received any direct sequels or spin-offs, Takahashi has borrowed heavily from it in every game he’s helmed since. The second is that Xenogears is one of the greatest and most ambitious games ever made, far beyond the scope of most JRPGs before or since, with a knotty, complex plot that openly incorporates elements of, among other things, Gnosticism, Jewish mysticism, and 20th-century psychoanalysis.

But most compelling of all—the foremost reason Xenogears has always functioned and will continue functioning as the skeleton key to Takahashi’s work—is the fact that it’s unfinished. The game’s precarious development cycle is, by this point, a legend unto itself, an inextricable meta-framework that clarifies and enriches the unevenness of the text.

In brief: Xenogears was huge. Its team was comparatively small, and lacked experience with 3D modeling and level design (unlike most JRPGs of its era, Xenogears boasted fully three-dimensional environments and a dynamic camera system). Ideas got bigger as deadlines got closer, and the developers faced a choice: release the game on one disc and end on a cliffhanger, or finish the story across two discs, with the second somehow shortened. Takahashi, preferring an imperfectly-told story to a half-told one, chose the latter. As a result, the final ~15 hours of the game are presented in a visual novel-adjacent format. Revelatory plot developments and large-scale conflicts are compressed into a patchwork of text crawls, displayed against sparse backdrops that, at times, resemble a stage. Prior to any of its spiritual successors, prior even to its own conclusion, Xenogears begins adapting itself.

This is all to say that Xenoblade 3, and indeed the entirety of Takahashi’s corpus, cannot exist in a vacuum. His debut project is one that practically begs to be relitigated and reinterpreted. All of his preoccupations are present here, in some form, at ground zero. To really get a handle on what he’s been building toward for the past twenty-odd years—on why Xenoblade 3 is, in its own way, a triumph—we need to perform our due diligence. We need to start with Xenogears.

(This piece contains spoilers for Xenogears and Xenoblade Chronicles 3.)

The First: Xenogears

Luckily, Xenogears isn’t actually that complicated. It’s just about love.

All of Tetsuya Takahashi’s games are about love. Even at their most convoluted, their most esoteric, and, yes, their most cringeworthy (hello, Xenoblade 2), they’re love stories. The man can’t help himself.

I’m being a bit facetious. Of course Xenogears is complicated, sometimes exhaustingly so—while replaying it in preparation for this piece, I frequently found myself tabbing between a Carl Jung study guide and several different passages from the Nag Hammadi codices—but its density is a means to a relatively clear-cut end. It poses a question, philosophically broad but emotionally precise: what does it mean to love something? To love another person, to love humanity, to love God? After about 60 hours, it arrives at something resembling an answer.

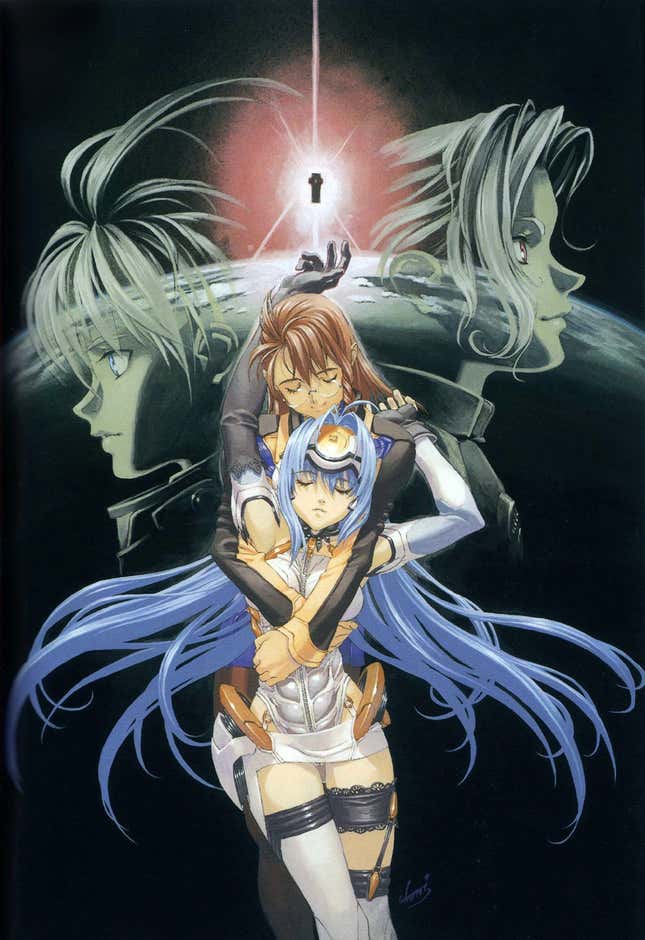

The circuitous path to that answer begins in the remote pastoral town of Lahan, in the country of Aveh, which has been at war with neighboring country Kislev for 500 years. The scales have tipped in Aveh’s favor due to its widespread usage of “Gears”: giant fighting robots excavated from the ruins beneath the country’s desert. After an Aveh-led black op gone awry embroils unwitting Lahan resident Fei Fong Wong—an amnesiac painter—in this conflict, he eventually stumbles into the discovery that both sides are being puppeteered by a third, far more powerful political entity called Solaris. Elhaym Van Houten (Elly for short), a high-ranking Solarian soldier, repeatedly crosses paths with Fei, and together they learn of a covert plot to resurrect an ancient biological WMD called “Deus” by supplying it with mutated human flesh. More importantly, though, they fall in love.

These ideas were not Takahashi’s alone. In the early ‘90s, while working at Squaresoft as a graphics artist, he became acquainted with fellow employee Kaori Tanaka (who now works under the pseudonym Soraya Saga). He and Saga shared a number of interests: science fiction, history, literature, religion, philosophy, psychology. Together, they began drafting a story. That story became Xenogears, and their friendship became a marriage.

Saga’s contribution to Xenogears cannot be overstated. By all accounts, she was responsible for the two ideas that would eventually form the narrative bedrock of the game proper, those being Fei’s struggles with multiple personality disorder and antagonist Miang Hawwa’s role as a feminine AI. Saga and Takahashi collaborated closely on both outlining and scriptwriting, and though she doesn’t share her husband’s director credit, it would not be an exaggeration to say that, conceptually and ideologically, half of Xenogears belongs to her.

Once again, it becomes impossible to decouple the circumstances of the game’s production from how it operates as a work of fiction. A story about love, written by two people in love, packed end to end with their mutual obsessions. Its philosophizing takes on an almost conversational quality: the more Xenogears breathlessly divulges its ideas, the easier it is to imagine it as a match of intellectual ping-pong between its creators, the result of years of discussion and debate and scrutiny and affection. The game’s unrelenting determination to see itself through to the end despite its concessions illuminates the compulsion behind it. Takahashi and Saga needed Xenogears to exist; it was their love made manifest. If it resonated with even a single person, that would be more than enough.

Thankfully, it resonated with plenty of people, because it’s a compelling, provocative game. Xenogears’ cult status is unsurprising: even on the most superficial level, it’s catnip for proper noun recognizers, pulling unabashedly and without hesitation from every imaginable creative stratum and allowing high, low, and pop culture to collide violently in the shifting currents of its ocean-vast design. This is a work as inspired by Jung as it is by Super Dimension Fortress Macross, as evocative of Arthur C. Clarke’s poignant novel Childhood’s End as it is of the Apocryphon of John. Government-operated facilities that turn people into food are called “Soylent Systems,” the quantum supercomputer overseeing all life on the planet is called “Zohar,” one of Fei’s former incarnations is literally named “Lacan.”

The weight of all these allusions threatens, at times, to break the bank. In isolation, they mean little. A story serving up a mile-high layer cake of intertextuality does not automatically render it intelligent or insightful. Xenogears certainly isn’t lacking in ham-handedness, but its influences are, by and large, only scaffolding, and invoked with utmost sincerity. They’re deftly channeled into our understanding of the world and characters, existing primarily to generate drama. The game is not smart because it references psychoanalytic theory and Gnostic doctrine. It’s smart because it understands how these concepts could meaningfully inform the identities and beliefs of human beings.

Fei’s splintered personalities and incarnations are an oft-referenced example, and for good reason: they’re patterned after a widely-known psychoanalytic schema (that being Freud’s theory of the id, ego, and superego), and lend themselves well to straightforward interpretation (Fei’s most antagonistic alternate personality is named “Id,” and much of the rest can be inferred). By the game’s end, this configuration has transcended metaphor and become a catalyst for an exceptional character study, realistically curdling Fei’s relationships with others and himself while drawing the curtain back on his most deeply held personal apprehensions. It’s telling that he doesn’t map precisely onto any particular model–these models are not, ultimately, the point.

This ethos is just as apparent in the game’s broader strokes. There’s a moment relatively early on in Xenogears when one of its major characters, Margie, gives the rest of the party a guided tour through a cathedral in her hometown. Margie is a spiritual leader by blood, and acts as something of a foil to her more literal-minded companions. She draws their attention to two enormous statues near the cathedral’s altar, each depicting an angel with only one wing. This blemish, she says, is by design. “God could have created humans perfectly, but then, humans would not have helped each other,” she explains. “So that is what these great single-winged angels symbolize… in order to fly, they are dependent on one another.”

Here the game generously offers us its thesis, and the thesis of more or less every Xeno game, on a silver platter. It suggests that divinity and weakness coexist symbiotically in human beings, and bridges that gap with a call to mutual aid. It asserts that people can find God in their own mortal lives, that helping and loving one another is the strongest possible application of faith.

That Xenogears has such a defined thesis at all is indicative of its thoughtfulness. The game is in active conversation with its influences; its conclusions are its own. Its primary antagonist, Krelian, is a pure Gnostic, regarding humans as deficient and taking drastic action in service of transcending the Demiurge (the aforementioned Deus, which functions as a conduit to a higher plane of existence). Fei rejects this. He knows he doesn’t need God to feel whole. He just needs Elly.

Fei and Elly are the beginning and the end. Their love is the grounding force behind every arcane reference, every serpentine plot thread. An artist and a soldier, adrift on opposite sides of a centuries-long war, find one another, and in doing so, find providence. The majority of Xenogears’ grandest thematic gestures—most of which would become Takahashi staples—orbit this relationship in some form. Spirituality, class warfare, familial trauma, systems of control, cycles of rebirth, lives as a resource, desire for community—all are addressed, explored, and embodied on an intimate, human level. It feels honest. Occasionally, it even feels adult.

It’s equally exciting and frustrating that most of these ideas only really hit full tilt in the game’s truncated final third. Disc 2 of Xenogears is one of the most texturally bewildering stretches of any video game I’ve ever played, lofty in its aims and deeply moving in its dedication but so clearly a mere trace of all it was originally conceived to be. As incredible as it often is, it aches to be more. Fans and detractors alike have opined that the game would be a paradigm-shattering masterpiece had it been fully realized, lamenting all the quests they’d never get to see and dungeons they’d never get to explore. Personally, I’m not so sure. Xenogears left me wanting, yes, but would filling in its gaps dilute the white-hot nitro burst of creative energy fueling its final hours? Would a “complete” Xenogears feel as raw, as authentic? Would Takahashi still be remaking it?

On one hand, maybe Xenogears needs its abridged disc 2. Its flaws dovetail rather poetically with what the game is trying to say about the virtues of human imperfection. On the other hand, it mostly stops being a video game, which is a shame because Xenogears is a video game for very specific reasons. The aforementioned 3D maps are crucial: this is a world built for tactility, for depth in the most literal sense. World immersion, it would eventually become clear, is one of Takahashi’s guiding principles as a game designer:

In terms of my own personal goal - my vision of an ideal game - I’d honestly have to say that [Xenoblade Chronicles] is barely 5% of the way there. My goal is to recreate the world itself. I think it’s valuable to develop projects with such lofty goals in mind. [...] I know this is a pretty radical idea, but I think the future of [the RPG genre] is world creation that is good enough to be the equivalent of reality.

-Tetsuya Takahashi, Nintendo Power (March 2012)

We can see this mentality germinating all the way back in 1998. Xenogears, for all its loquaciousness, wants us to play it. Its environments are beautiful, meticulously constructed dollhouse dioramas that encourage viewing from every angle, and its dungeons, for better or worse, have platforming. This floors me. In an era when even 3D platformers were still figuring out 3D platforming, Takahashi and co. plunked it right in the middle of their madcap anime role-playing game, taking extra care to consider how the areas interlocked in 3D space and what that could communicate about the world to the player. The quality of the platforming (not great) is beside the point. It’s the gesture that counts, and it counts for a lot. It brings us closer to that world. It brings us closer to the characters. We are participants in Xenogears, not observers. Welcome to interactive storytelling.

So we play the video game. We explore the world. We kill the monsters. We pilot the robot. We get the girl. We watch the cutscenes. We fight God (sort of). We win; roll credits. Finished at last, we breathe a deep sigh and begin mulling it all over. Then one final morsel of text fades onto the screen. “XENOGEARS EPISODE V: THE END.”

What the fuck. V as in 5?

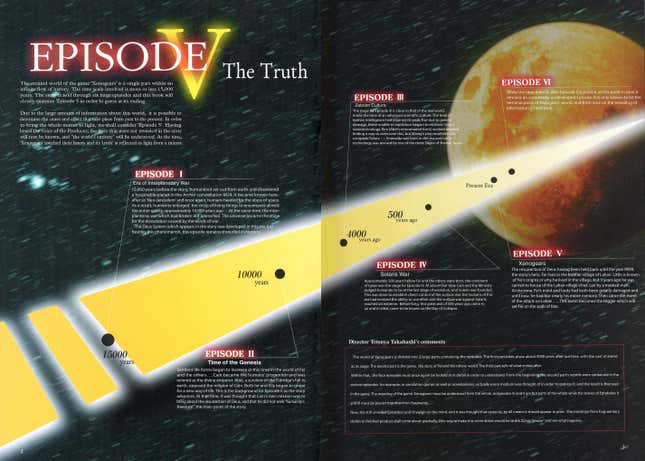

Xenogears, as it turns out, is even bigger. During the initial planning phase, Takahashi and Saga conceptualized a 6-part timeline stretching from the beginning of the game’s continuity to its end. Part 5 constitutes Xenogears’ “present day”–in other words, the game itself. Parts 2-4, though not playable, are discussed in great detail. Parts 1 and 6 are practically untouched. At no point are any of these demarcations established in-game. It wouldn’t be clear what “Episode V” meant until the official Xenogears art book, titled Perfect Works, laid it all out two years later.

Perfect Works—which, even in name, suggests a mythic, tantalizing vision, a towering opus that has yet to be realized—quickly became shorthand for Takahashi’s creative aims. When people realized just how much story he and Saga had wanted to tell, they began applying Perfect Works as a blueprint, wondering aloud if any of his new projects would finally convey it in full. As recently as Xenoblade 3, the speculation persisted: “Is this it? Is he finally doing Perfect Works?”

The answer is complicated.

Interlude: Xenosaga and Xenoblade Chronicles

In 1999, Takahashi and several members of the Xenogears development staff split from Square and formed their own studio, Monolith Software, Inc. Their first project, published by Namco and released in 2002, was Xenosaga Episode I: Der Wille zur Macht.

If the brazen Nietzsche reference in the subtitle wasn’t an obvious enough tip-off, Xenosaga Episode I is every bit as philosophically dense as its predecessor. Another collaboration between Takahashi and Saga, it lifted numerous concepts very directly from Xenogears—most notably the Zohar, and its connection to the “upper domain” of the universe—and recalibrated them for an epic space opera. As a story, it’s intricate, absurd, emotional, and only occasionally dull. As a game, it’s dull slightly more often. I played it some years ago, and was fascinated by it. I have not played its two sequels, Xenosaga Episode II: Jenseits von Gut und Böse (2004) and Xenosaga Episode III: Also sprach Zarathustra (2006). Someday I will, and I’ll be fascinated by them, too.

Xenosaga’s fate was much the same as Xenogears’, this time stretched out over several installments. It was first envisioned as a six-game arc—as good an indication as any that, yes, this was Perfect Works 2.0—but complications stemming from Episode I’s rushed development resulted in that number being halved. Takahashi and Saga wrote the script for Episode I. For Episode II, they wrote a draft, which was then drastically altered by the rest of the team to accommodate a tighter scope. By Episode III, Takahashi was only working on the series in a supervisory capacity, while Saga had stepped down altogether. To date, Episode II remains her last scriptwriting contribution to a mainline Xeno game. (She would, however, help write the 2004 mobile spinoff Xenosaga: Pied Piper and the unrelated 2008 Monolith Soft game Soma Bringer. She also contributed to Xenoblade 2 as a guest artist, designing the character Yuuou (which, for some reason, was translated into English as “Gorg”).) Though Episode III was critically well-received, its lackluster sales left Monolith Soft’s future uncertain.

There’s a great deal to be said and written about Xenosaga’s own status as a compromised work, and how it applies its uniquely heady, off-the-wall ideas (Jesus Christ—as in Of Nazareth—is an actual character in these games, chunky PS2 graphics and all). For now, these considerations fall outside my purview. Just know that it’s big, messy, beautiful, and at least 60% Xenogears.

Monolith Soft was bought by Nintendo in 2007. Xenoblade Chronicles, Takahashi’s next major project, released in 2010. At that time, it was by far the most “complete” game he’d ever directed: a sprawling JRPG with a self-contained story, polished to a high sheen from start to finish, featuring colorful, well-rounded characters and an energetic real-time battle system. Everything about its design and presentation straddled the line between old and new. Originally, it was localized only in Europe, in 2011. Thousands of people, me included, wrote letters to Nintendo urging them to release it in North America. In April of 2012, they did. It’s my favorite game of all time.

Over the following five years Xenoblade spawned two sequels, the first one spiritual. Xenoblade Chronicles X, released in 2014, is perhaps the best example yet of Takahashi’s interest in world design, purposefully eliding much of its story in favor of giving players nearly unrestricted access to a gargantuan map. It’s the only Xenoblade game thus far to feature controllable mechs, and for that alone, it gets the gold star.

Xenoblade Chronicles 2 (2017) would be one of the worst games in history if it wasn’t one of the best. Its design is a queasy fractal of systems within systems; its aesthetics simultaneously evoke the imaginative whimsy of SNES JRPGs and the screaming-loud numerical bacchanalia of contemporary mobile gachas. At times, it’s agonizing. At others, it’s delightful. Eventually, it trips headfirst into saying something really interesting. I like it, because I like weird stuff. Your mileage may vary.

It also marked the series’ transition to something unexpectedly complex. Prior to its release, Takahashi said that the game, as with X, would be a separate continuity, à la new mainline Final Fantasy entries. This was a bald-faced and hilarious lie. The final act of Xenoblade 2 established a cosmic, millennia-spanning throughline between itself and the original Xenoblade, jettisoning lore fragments in a thousand different directions and leaving the series wide open to further exploration.

Xenoblade was never meant to be a multi-game project. It wasn’t meant to be Perfect Works. And then, suddenly, it seemingly was. One can only assume that Takahashi used the first game’s success as an excuse to dig his heels in. This was to be his new outlet. Maybe, this time, he could finally bring it home.

On February 9th, 2022, Nintendo announced Xenoblade Chronicles 3.

The Last: Xenoblade Chronicles 3

Immediately, the game looked familiar.

There were the designs, for one. Xenoblade 3’s ponytailed protagonist Noah bore a not-not-striking resemblance to Fei, and one of the first revealed villains, Consul D, was nearly the spitting image of Xenogears’ Grahf.

But these similarities were only skin deep. The game’s story, even with the scant information provided in the reveal trailer, was far more enticing. It supposedly concerned two nations, Agnus and Keves, locked in an eons-long war for reasons long forgotten. (Pop quiz: what other Takahashi game features two warring countries whose names begin with the letters A and K? You have five minutes.) Its central party was to be composed of two groups of three characters each—three from Agnus and three from Keves. Noah would lead the Kevesi group. The Agnian group would be led by a girl named Mio. It didn’t take an accredited Takahashi scholar to predict that Noah and Mio were probably going to fall in love.

They did, of course. I just wasn’t prepared for how much.

Not unlike Xenogears, Xenoblade 3 features an early scene that defines its goals more succinctly than I ever could. In the aftermath of an intense battle, the two groups of characters—still enemies at this point in the story—sit down and, understanding that they’re bound by circumstance and have no choice but to cooperate, introduce themselves to one another. They go around in a circle, say their names, and talk about their interests. It’s so sweet and so remarkably simple, and the simplicity feels like the point. Here are six people whose lives have been defined, in every imaginable way, by conflict. When the stakes suddenly change, words are all that are left. Aggression yields almost immediately to emotional honesty.

Emotional honesty is vital in Xenoblade 3, which takes place in a deeply dishonest world. Every facet of it is designed to disallow growth and discourage connection. People aren’t born, they’re made. They live ten years at most, fighting the entire time. If they don’t fight, they die. After they die, their physical forms are reconstituted and their memories are wiped, and then they do it all over again. All in service of a war that, it’s soon revealed, is a farce orchestrated by an organization called Moebius, members of which draw sustenance from the bodies of dead soldiers and preside over human encampments like petty tyrants. They do this so they can live forever, because to be mortal is to invite change, and nothing is more frightening than change.

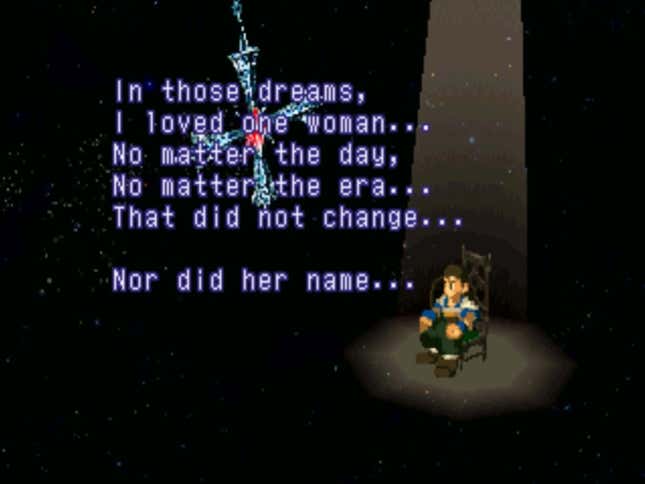

As always, love is the antidote. The operatic, time-transcending romance between Noah and Mio, echoing that of Fei and Elly, functions as a microcosmic distillation of the plot’s overarching conflicts. As “off-seers”—soldiers tasked with mourning the lives of their fallen comrades—they’re acutely attuned to cultural memory, or lack thereof. Together, they realize that uncertainty is preferable to stagnation, and that imperfection begets improvement. They see a hideous, mangled variation of their relationship in the characters N and M, who relinquished their humanity in favor of eternity, and decide to do better. Indifference becomes their greatest enemy. If the world prevents their union, then so be it: they’ll remake the world. Why wouldn’t they? Their love is stronger. Any system obfuscating it has no reason to exist.

The game’s definition of “love” extends far beyond just this central couple. Xenoblade 3 distributes dialogue fairly evenly among its main cast, and exhibits on average the highest quality of character writing in the series—a considerable improvement over the already wonderfully grounded Xenoblade. (Xenoblade 2 is Xenoblade 2.) A great deal of thought is put into particular frictions of even minor conversations, and before long, a friend group organically takes shape. Having painted a vivid picture of its unjust, overbearing world, Xenoblade 3 contends that nothing is more restorative than companionship. X-ray its story and you’ll find the skeleton of a road movie.

Companionship is, in fact, what much of the game’s design is predicated on. Its quest structure is boldly, confidently ridiculous: instead of simply talking to NPCs to get sidequests, players instead need to “overhear” NPCs voicing concerns, and then convene at a “rest spot” (usually either a campsite or a restaurant) so that the party can talk these concerns over at length, each member offering a distinct perspective. Only upon completion of this entire process, which often takes several minutes, is the quest made available. From a utilitarian standpoint, this is cumbersome. It adds several unnecessary steps to what should be a rudimentary and straightforward action. From a chilling-with-your-homies standpoint, it’s perfect. It speaks to Xenoblade 3’s desire to cram as much characterization as possible into every square inch of both playable and non-playable space. The game desperately wants us to understand these people, given what limited time they have.

Zoom out a bit and you’ll see this philosophy applied everywhere. The battle system functions as its own sort of interaction, with each character having the option to use any other character’s class at any time–a mechanic introduced following a scene where the entire party trades compliments. The brilliant “affinity chart,” which tracks every named character in the game and their relationships with one another, returns from the first Xenoblade. And many of these characters are folded into the main cast via “hero quests,” extended side stories focusing on notable NPCs with uniquely fraught connections to the war. Free them from Moebius’ control and they’ll join your party as optional seventh members, opening the floodgates to yet more conversation and further deepening the player characters’ involvement in the communities—and world—they inhabit.

That world (called “Aionios,” derived from Greek “aionioß,” meaning “without beginning or end”) is especially noteworthy, because worlds are Takahashi’s bread and butter, and ever since the original Xenoblade he’s taken a particular interest in their decline. Even sans impending doomsday scenarios, the settings of all three games in the series exist in varying states of sustained putrefaction. Xenoblade and Xenoblade 2 both take place on the bodies of massive living creatures that, due either to inadequate sustenance or resource mismanagement, are dying. 3, which merges the settings of its two predecessors, is a colossal graveyard, its landscapes littered with these creatures’ ancient, petrified remains. Strange explosions dubbed “annihilation events’’ frequently atomize large swaths of terrain without warning, gradually eating away at what little is left. Aionios’s denizens all intuitively understand that it’s dying, if not already dead. They’ve just been conditioned to accept it.

It seems only natural that climate anxiety would eventually take root in Takahashi’s fiction, preoccupied as he is with notions of environmental hostility. His worlds are in active contention with their populations, usually as a result of humanity’s severe technological overreach. In Xenogears, this comes as a shock. In the Xenoblade series, it’s a given. Even when characters know little about their respective world histories, they know these worlds are impermanent and that their decay is accelerating. The challenge, then, is one of overcoming apathy.

Apathy as moral failure, and the subsequent effects of failure on the human psyche, were embodied in Grahf, one of Xenogears’ recurring villains (and yet another incarnation of Fei). Grahf’s inability to protect his loved ones resulted in a despair so overwhelming that he elected to be its agent rather than its victim. Xenoblade 3 iterates on this with the character N, a former incarnation of Noah, whose cruel disposition stems from his reluctance to acknowledge the impermanence of life–his own, and that of his partner. He fought back against Moebius, failed, and then sided with them, because in his cowardice he couldn’t bear failing again. For N, love is a corrupting force, not a healing one; it can be weaponized like anything else. He’s the most emotionally resonant antagonist the Xenoblade series has yet seen, and the dialectic between him and Noah—who tells him, to his face, that he’s full of shit—is a tidy summation of ideas Takahashi has toyed with for decades.

Xenoblade 3 is chock full of familiar gestures, taken to their logical extremes and amplified to a fever pitch. It’s loud, bright, and relentlessly earnest, and it packs more than a little revolutionary spirit. Closely examine even its gloomiest moments and you’ll find traces of celebration, of both its forebears and of itself. Gameplay is sharpened to a keen edge, level geometry is beautifully constructed, the plot is meaty, and the romance hits like a freight train. Seeing it all unfold with so much verve, knowing about all the curtailed projects that preceded it, is moving. Xenoblade Chronicles came more or less out of nowhere; Monolith Soft’s post-Xenosaga future was anyone’s guess, given Episode III’s underwhelming performance. Twelve years later, Xenoblade is a distinguished franchise, its ambition budding with each installment. Takahashi, with the aid of his peers, finally pulled it off.

And so, as is tradition, that timeworn rallying cry: “Perfect Works?”

Xenoblade 3 is superb. It is not, however, Perfect Works.

At least, it isn’t Xenogears. This seems to be the underlying assumption behind every piece of Perfect Works-related speculation: at the end of the day, people just want Xenogears, or at least something narratively identical but with all the names switched around. I can’t blame them, especially when Xenoblade 3 very intentionally teases out these reactions. Thematically, the two games overlap quite a bit, and Xenoblade 3 is indeed a culmination in a more general—and, I’d argue, more meaningful—sense. But it can’t be Xenogears. It doesn’t have enough ideas, and the ideas it does have aren’t interesting enough.

In all fairness, the same can be said for most games that aren’t Xenogears.

Speaking to Satoru Iwata in 2010 about the first Xenoblade, Takahashi said the following:

When you’re young, you’re brimming with creative energy after all, and it is a path everyone goes through. Among young game creators today, there is no shortage of people with the same approach I had, making games solely for those players who will understand what you are trying to achieve. I think that this sort of game is necessary in the video game industry.

But now, when I ask myself if I still have that drive, which was in a sense rash and reckless, the answer is of course that I don’t. At the same time, I now have a better view of the overall shape of things, and I feel that my creative range has increased. Recently, especially since becoming a father of two, I’ve been thinking more and more about how to make a game that will be enjoyed by a large number of players and that will strike a chord with them.

-Tetsuya Takahashi, “Iwata Asks: Xenoblade Chronicles”

Admittedly, this gnaws at me. Takahashi’s overt admission that his new work lacks the hyperspecificity and unchecked passion of Xenogears and Xenosaga calls into question the value of Xenoblade as a product of personal expression. It also prompts me to re-evaluate my own relationship with it. Again: Xenoblade Chronicles is my favorite game. My love for it was (and is) owed in no small part to my perception of it as a thoughtful artistic gesture, in addition to its merits as both a video game and a work of fiction. It affected me in a very particular way at a very particular point in my life; maybe, if it were released now, my feelings would differ. In any case, putting it in conversation with its progenitor, I’m confronted with the realization that it may itself be compromised. Not in the literal, conspicuous way that Xenogears is, but in the subtler, more cynical way that so much art beholden to capital is. Mass appeal, tempering of difficult ideas, and diminished creative breadth.

To an extent, I’m sure this is true, because this is how creating in corporatized spaces works. With video games’ maturation into a lucrative global enterprise, risk-taking projects with the ideological heft of Xenogears have become rarer, at least from developers as high-profile as Square. Xenoblade and its sequels are bankrolled by Nintendo, one of the most recognizable corporate media entities in the world. Conclusions vis-à-vis limited artistic freedom are easy to draw.

But Tetsuya Takahashi is also a human being. Human beings change. At the time of the above quote, Xenogears was over a decade old. This year, it turned 24. Takahashi notes that since its release, he’d become a father, and consequently viewed the shift in his priorities as liberating. Retooling his interests for a wider audience was, in his view, a new and refreshing way to approach game development. If I’m being charitable, it sounds like a personal choice. And I want to be charitable, because I love these games, and because I believe this interpretation is supported by the text.

Though the series may lack Xenogears’ rougher edges, Takahashi’s fingerprints are still here, and they’re not particularly hard to find. The weapon wielded by Xenoblade’s protagonist explicitly references Leibniz’s Monadology; Xenoblade 2 is a frenzied riff on Plato’s allegory of the cave; all three organize their heroes and villains around Gnostic concepts. More importantly, though, they are—as with Xenogears—anchored by the thoughts and actions of people, and are concerned chiefly with the importance of community amid systems that discourage it.

Xenoblade 3 is a culmination because it’s Takahashi’s most potent love story yet. Its sincerity is all-encompassing. As I played it, three things became clear: one, that it’s a game written by a real human being with real human interests, not an automaton who has dedicated his career to clinical self-imitation. Takahashi understands better than anyone that truly “remaking” Xenogears means excavating the pathos from its core and refining it even further. (Fittingly, the most formally congruent scenes between Xenogears and Xenoblade 3 are montages in which two lovers repeatedly reconnect throughout thousands of years of history.) Two, that he is thinking very candidly about death, and what it really means to surrender oneself—and one’s family—to the future’s unknowns. And three, that this is, on a purely emotional level, the game he’s always wanted to make. Perfect Works, which largely fails to account for the emotional underpinnings of Takahashi’s work, is not a sufficient blueprint. Xenoblade 3 is similar in the ways that matter most, and different only inasmuch as its creator has changed.

In its final moments, the game pulls a crafty narrative trick. Having asserted that overinvestment in the present stymies acceptance of the future, it implicitly incriminates players who don’t want its story to end. The broader connotations of this, intentional or not, are not lost on me. Tetsuya Takahashi will probably never make another Xenogears. If he does, it may not even be on purpose. Instead, he’s making something new, something informed by but not derivative of his past. Xenoblade 3 is a culmination, not a retread. It looks forward, not backward.

It is, as with everything Takahashi has made, a creation myth.