My kids have started playing Wind Waker recently—for the record, my favourite game of all time—and it’s been a joy seeing them encounter everything for the first time. Gasping at Aryll’s abduction, laughing at the Killer Bees, screaming “this stealth level is the worst I hate it”. I wonder, though, what they’ll make of the game’s ending, if they ever get there.

Time is a funny thing. It’s almost a historical footnote by now, lost to the sands of time, but it’s worth pointing out that when Wind Waker was first released back in 2003, lots of people—some of them in influential positions in what was back then “the press”—hated it. The game’s seemingly childish visuals were seen as a betrayal of a maturing medium, a deviation from Zelda’s GameCube demo, a step backwards from the critical and commercial highs the series had enjoyed on the Nintendo 64.

Hahaha, whatever, dorks.

We’ve all but forgotten this by 2020, because the game’s actual strengths—its timeless visuals, elegant combat controls and pioneering open world design—have carried it to a storied place in not just series, but video game history.

One of the things I loved most about Wind Waker was that, despite its cheery visuals and outward innocence, there was some dark shit lurking deeper in its storyline. While the game’s early chapters were all about traversing the deep blue sea, the wind in your hair, getting sails for a talking red boat and doing some sight-seeing with little talking leaves, as you progress deeper in the main storyline you start to find that Wind Waker’s heart is a lot darker than its wardrobe.

It’s Mad Max set in Hyrule.

The entire premise for your tropical island getaway is that Hyrule eventually lost one of its generational struggles, Ganon emerged triumphant and the entire kingdom was sunk beneath the waves in a Hylian Ragnarok. Everything you’d fought for in previous Zelda games was gone. The people you encounter, clinging to life on the few remaining spots of dry land, aren’t nautical by choice. They’re post-apocalyptic survivors.

And yeah, while Breath of the Wild also takes place after a cataclysm, it’s a societal one, a once-mighty Kingdom reduced to ruins. At least the land itself is still there.

Despite this grim setting, the game is actually (for something so dependent on combat, at least) very light on violence. Sure you kill a bunch of things, but the consequences of this are softened by the cheery musical notes playing with each swordstroke, and the fact enemy corpses disappear in clouds of gorgeous, swirling smoke. You may be committing wholesale homicide, but it’s as gentle and PG as wholesale homicide gets.

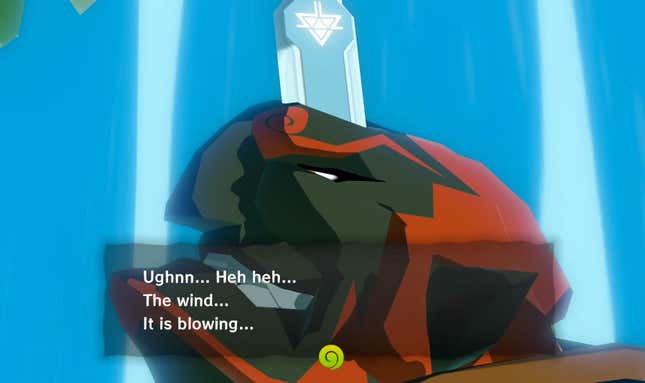

Until the end. After enduring a fairly disappointing final fight against Ganon, the killing blow is delivered via cutscene, where Link vaults up into the air, brings his sword down and wait what?

He drives his sword deep into Ganon’s fucking skull?

And the camera just lingers there, forever, dwelling on it?

And Ganon is STILL TALKING, WITH THE MASTER SWORD COMING OUT OF HIS FACE?

AHHHHHHHH

So much for keeping things PG. The cartoonish restraint of the preceding hours only serves to emphasise the brutality of the game’s final blow. Every other kill you’ve made has been a jolly little victory. Here, it is murder, and it’s stark, and memorable.

I remember playing this for the first time at release, huddled around a GameCube with the friends I’d been couch co-opping with, and just losing my damn mind. While the fight itself was a let-down (and, really the last few hours leading up to it), its conclusion is easily the most satisfying dispatch of Ganon in the entire series.

Partly because of the graphic nature of the kill, sure, but it’s also a surprisingly tragic scene. This is my favourite Ganon in all of Zelda. His appearance is just right, his size and posture fittingly menacing, but he’s a more sympathetic and rounded character here than we’re used to. As an unstoppable force of evil (like he is in, say, Breath of the Wild) he’s just a narrative fixation, an obstacle with a name, but here, as a ruler who only had the interests of his people at heart, and coveted that which his neighbour enjoyed, he’s a relatable character, one we can empathise with for his motivations while simultaneously revelling in his demise for his actions.

Wind Waker’s conclusion is a wonderful case of Nintendo reminding us all never to judge a book, or a game, by its cover. The game’s visuals and even opening sections had put a lot of people off at the time, dismissing this as child’s play. Those so swift to write the game off were missing out, though, on one of the most rounded and mature Zelda storylines the series has managed, one where sacrifice and failure are as prominent as heroism.

And nowhere is this more evident than at the very end. As smoke-filled combat gives way to grisly murder, as Ganon’s final words slip out of his still-twitching body, there’s even sadness to be found in your ultimate victory. Defeating Ganon doesn’t somehow save Hyrule, or restore the fallen kingdom to its place above the waves. You’re simply returned to the surface, and told to get on with it.

I can’t keep count of the moments from this game that have stuck with me 17 years, from Dragon Roost’s theme to catching runaway pigs, but its Wind Waker’s grisly finale that haunts me more than any other.