Shigeru Miyamoto, esteemed creator of Mario, Donkey Kong and Zelda, usually does interviews to hype big new Nintendo game releases. A new Mario game is coming out? He’ll talk about that. New Star Fox? He’s down to talk Star Fox. But when most of Nintendo’s games upcoming games are secret? That was the situation last month. Thankfully, he was game for a different kind of talk.

I talked to Miyamoto last month in a meeting room in Nintendo’s E3 booth at the Los Angeles Convention Center. A demo copy of the new Zelda, Breath of the Wild, was set up nearby and was clearly on his mind, but we didn’t discuss it much. Instead, we talked about how Nintendo makes games, the advice he gives to people who work for him and the difficulties of designing good game controls, among other things.

I asked my questions in English, and he replied in Japanese. As is the norm, Miyamoto didn’t need my questions translated. Sitting nearby Miyamoto was Nintendo of America director of product marketing Bill Trinen, who has translated for Miyamoto for many years, but, this time, chimed in with some of his own thoughts to expand our conversation.

At one point, the 63-year-old Miyamoto laughed off the implication that he wasn’t a young man anymore. “I personally don’t feel like I’ve gotten old,” he said. He doesn’t act it either. Lively as ever, he seemed full of energy and was intriguing to talk to.

(The transcript has been lightly edited for clarity.)

Kotaku: What goes into making a Nintendo game special? How do you know when a game is good?

Shigeru Miyamoto: Ultimately I want a lot of people to enjoy the game, but the initial barometer and gauge is whether I enjoy it or not. Another thing is whether the uniqueness is maintained in a game as a Nintendo game, compared to [games from] other companies.

Kotaku: What do you mean by uniqueness? What do you think sets a great Nintendo game apart from other games?

Miyamoto: It could be how to play the game or some of the techniques or technology being used. There’s always a limited amount of things that we can use, so it’s how we use that and in what combination. So it’s really–instead of creating–a little more like editing, in a sense.

This becomes a little bit of a conceptual talk, but I think what’s really important is that there is a core [to the game]. And, based on that core, we use technology ... to develop the game. I think what a lot of people see as unique is using different technology or different techniques [to make games], but I feel like, as long as you have a core that’s unlike others, that’s what ‘unique’ is. So we can be using the same kind of technology, the same kind of techniques, but when we use it, we get something different.

Kotaku: What is that core of a game? Is that, for you, something you actually feel with your hands, because it is about interactivity?

Miyamoto: I think it comes down to the experience of the customer or people playing the game. It’s something we do with the Wii U. You can only experience playing a game with two screens on the Wii U, and it’s really about using the past techniques and technology that we’ve used before. We keep at it, and at the end of that we discover something new.

So even with a Zelda world that is about swords and magic, if we were to make it 3D and really realistic, and render the player realistic, you’d run into games that are just like that all over the place.

And so Zelda is really about exploring and adventuring [through] the land. And you’re kind of fighting against the land as if you were hiking in real life, and that’s how this game works. And the player has to think for themselves and has to put their ideas into practice. That’s what this game is.

Kotaku: With this game, Breath of the Wild in particular, Bill [Trinen] and Nintendo localizer Nate Bihldorff talked about how it harkens back to that original NES Zelda which you obviously were greatly involved in. And that seems to have a similar core to what you’re talking about here. It’s a similar theme. It’s you, the wild nature around you, and having to engage with that. Is that concept of Zelda something you’ve always carried with you with every Zelda game you worked on? And did you feel a desire to more strongly get back to it here?

Miyamoto: I think we definitely, as a development team, felt that is something that should be the core. That is something we discussed as a staff. But as we progressed in the Zelda franchise, a lot of how to implement it became very important. So dungeons became bigger and more complex. As it becomes bigger and more complex, the order that you navigate them becomes more necessary. The tutorial becomes bigger. We always felt that core is very important and crucial, but what resulted kind of strayed from it. And that’s the dilemma we were kind of fighting for. When we implemented the physics engine in this game and were able to explore the land freely, it resulted in going back to the roots and core of what Zelda is. And that’s something we’re happy about.

Kotaku: Does that in some way make you feel like you’ve come full circle? Back to your youth in some way? As a younger designer, I mean.

Miyamoto: I personally don’t feel like I’ve gotten old, so it’s not like I’m going back. But I really do feel like we were able to create something where the player is able to enjoy all of that.

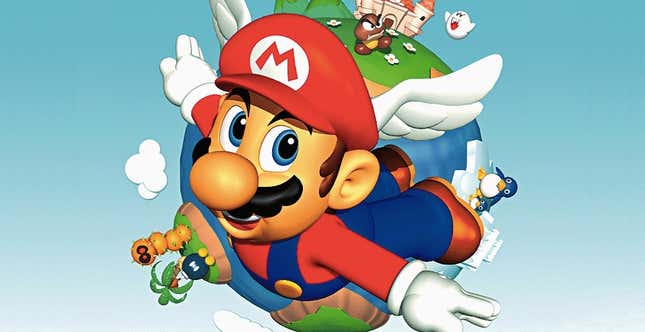

Kotaku: When I’m thinking about what sets a Nintendo game apart, often it’s the feel of it. It’s the controls. It’s how Mario jumps in Super Mario 64, which just feels so good. I can’t explain in words why that is. And I feel that in the better Nintendo games. I assume you feel it, too. How important are controls, and how hard is it to get them to feel as good as they feel?

Miyamoto: So you know programming is all about numbers. The challenge is getting this kind of feeling into numbers. So there’s a lot of back and forth between the programmer and myself and the director. We really go in deep about how to create this feeling. We do a lot of back and forth.

Bill Trinen: It actually goes back to the way they designed the original Super Mario Bros., where when they tested it, originally, there was no Mario and there was no person. It was just a block. And you would press the button and see the block move. There’s actually a word in Japanese that describes what you’re talking about–the feeling–which there is no word for in English. In Japanese it’s called tegotae...

Miyamoto: ... tegotae...

Trinen: ...which if you were to translate directly sort of means ‘hand response.’ There’s also hagotae, which is the sense that you get on your teeth when you’re eating food. Tegotae is the word that you’re describing when you talk about that feel of a Nintendo game and it goes back to the focus on the notion of pressing a button and what happens on screen and how do you feel.

Miyamoto: So the next one is weight. It’s really important to make the player feel as if they are there. There are many different ways to create the idea of weight. So, for example, if someone jumps from a high place, how long that character stays there.

I think the other thing is response. If we really wanted to make something look pretty, we would just have animator create it and you would just replay it. But there’s no sense of control there. If a character is in front of a wall and they start moving like they’re not in front of a wall, it creates that disconnect. And it becomes unnatural. So it’s really about taking what the animator does and polishing it up and making it so it’s interactive.

Kotaku: The sound effects also seem to me like a signature. They often feel related to the controls. I think I read in an interview that you gave many years ago where you talked about the sound effects–weight might be the wrong way of putting it–but there’s a substance to the sound effects. Is that a priority of yours as well?

Miyamoto: So especially in Breath of the Wild, the ground is really there. The player is walking on it. The player sees the grass and the rocks, but program-wise it’s obviously not really grass and rocks. But it’s really how we use the sound. So when you’re in a forest, we try to play sound effects that really remind you of a forest. So if a player goes into that forest, they’re reminded of a forest that they know.

Really, a game is about helping the player remember what they know. And that creates the illusion that they are there. In that sense, sound effects are necessary, and I think Nintendo always taken the time to create the sound effects. For example, checking the ground that the character is running on and making sure it matches that. We use a combination of the skills that we’ve had and what’s available now to create this.

Trinen: That’s why I love this game so much. When I lived in Japan I used to do a lot of hiking. I used to hike by myself a lot. And it’s amazing kind of tapping into the visuals and the sound effects and how they remind me of how I used to go out into the mountains on my own, trying to follow these trails and climb up these peaks and get that breathtaking view. It’s really just resonates with me.

Kotaku: Yeah, sound can definitely bring you back.

Miyamoto: And I think when you’re hearing the sound, the wind or when you go underground you hear this echo, coming up with ideas and throwing around ideas is really, really fun. He might have said if you hear this sound of falling rocks it might trigger this kind of memory. Throwing around ideas like this is a lot of fun.

Kotaku: At this point, a lot of the sound in newer Nintendo games, of course, reminds me of the sounds of older Nintendo games. Bill was talking about references and memory as it related to real life. But also now the newer games you make are also reminding people of the older games that they played.

Miyamoto: There’s also things like melody or music that does that. Now, these days, people play with headphones. I think playing on the headphones is also a really great experience.

Kotaku: When you’re working with younger game designers, whether it’s on this game or other games, what advice do you find yourself often giving them? Do you see them making mistakes that you made as a younger designer and find yourself giving certain key pieces of advice to people?

Miyamoto: I think, in terms of directors, they are sometimes vague. They might tell the programmer, ‘Alright, the enemy chases the player.’ That’s kind of vague. So, a lot of times, it’s up to the programmer to have to kind of figure out how that happens and how they make that into a reality. It’s about: How exact or vague are you being? When you say: the enemy checks the player every 10 seconds, is that vague? Or it does every 10 seconds, five out of those 10 times they make a mistake. Those are the details, and I try to tell everybody to make sure that they include those details when they talk to the programmers.

And not just directors, but any kind of person in a management role: leaders should be more specific, I tell them. [laughs]

Kotaku: It’s a tricky balance, though, right? You don’t want to feel like you’re micromanaging somebody and telling them everything to do.You want to give them some freedom. But if you’re not specific, as you’re saying, they may not do anything.

Miyamoto: But it’s not like I’m trying to force them to do this. If you give them specific instructions you get specific feedback. What happens is the discussion that gets born from there is really important, too.

And just like that, the Nintendo PR rep nearby told me we had time for one last question. So I asked him about the experience of delaying games, something I’d also discussed with longtime Zelda producer Eiji Aouma. You can read about that here.

The interview came to an abrupt end, but, as always, it’s to be continued, the next time Miyamoto wants to talk.