Within 15 minutes of opening the package containing the Oculus Quest, Facebook’s new standalone virtual reality headset, I was playing a game. I wasn’t playing some watered-down mobile phone app or preinstalled demo, but a full-featured, console-quality VR game. This is great.

The Quest is Oculus’ first all-in-one gaming headset. It requires no PC connection, unlike the original Oculus Rift and its recent upgrade, the Rift S. Like last year’s Oculus Go headset, the Quest is completely wireless. But the Go was virtual reality at its most basic, just a headset with a pair of monitors inside. The Quest has all the VR bells and whistles. It can track head and hand movement and room-scale body positioning without the use of external sensors. It’s the full virtual reality experience in one box. Bear in mind the price. It starts at $399 with 64 gigabytes of storage, with a 128 GB version available for $499 (I’ve got 16 games and apps loaded on my 64 GB unit and am only using half the space).

There’s not a lot inside the Oculus Quest box. There’s the headset, an understated design wrapped in textured cloth. The front is matte black plastic with four cameras in the faceplate’s four corners, which are used for the headset’s inside-out tracking. There are a pair of redesigned Oculus touch controllers. The original controllers had rings on the underside to be tracked by external sensors, where the new ones have rings on top so the headset cameras can track them. There’s a pair of batteries for the controllers, a face spacer for users with glasses, and a single wire—a USB type-C charging cable.

All one needs to set up the Oculus Quest is an iOS or Android device running the Oculus app. The app is used for the initial hardware setup, connecting the unit to Wi-Fi and such. A quick setup sequence will pair the controllers (mine were paired right out of the box) and walk the user through adjusting headset position and lens spacing. The user defines a safe play area by tracing empty space with their Touch controller. From there they are free to browse the store, play games, fiddle with apps and explore the Oculus VR environment.

Once the Oculus Quest is configured, entering virtual reality is as simple as slipping on the headset. I can’t overstate how amazingly simple and worry-free the process is. I’ve used the original Oculus Rift and the HTC Vive, and the biggest obstacle to my enjoyment is the initial set up. I’d have to plug and unplug HDMI cables to and from the back of my PC, set up satellites and sensors, make sure those sensors could see my headset, and keep my headset tethered to my computer via thick cables—tethered to normal reality. The Quest cuts all those cords. It’s full-featured virtual reality that’s easy to transport and easy to share.

Last month I attended the Atlanta anime and gaming convention Momocon as one of the judges of its annual indie game awards. My fellow judge, Vlambeer’s Rami Ismail, broke out his Oculus Quest in the judging suite late on Friday evening. A group of us had a blast playing Keep Talking And Nobody Explodes, Rami manipulating a virtual explosive device while myself, Destructoid’s Chris Carter and IGN’s Janet Garcia walked him through the defusing process. It was spontaneous virtual reality fun that’s just not possible with a device that needs to be wired to a PC and depends on external sensors.

Freedom from cords is very important to me these days. Last year I found myself paralyzed from the chest down. My days are spent either in bed or in a 470-pound electric wheelchair. Getting tangled up in wires was bad enough when I could walk. If wires get caught up in my wheels, the hardware is going to die. With no wires save the power cord, the Oculus Quest leaves me free to spin about my office with abandon. The defined safe play area lets me know if I am getting too close to obstacles. Should I stray outside of it, the external cameras on the headset automatically kick in to show me where I am and what I am about to destroy. It’s actually quite a bit of fun, being in virtual reality in a wheelchair. All I need now is a Doctor Who game that lets me play as a Dalek, and I am set for life.

Being a self-contained piece of hardware has another benefit. Games and apps made for the Quest can be specifically tailored to its specifications. Developers don’t have to account for an endless array of PC hardware configurations and can focus on delivering the best experience possible. Oculus is curating the Quest store to ensure apps and games for the device are the best they can be. According to the official submission guidelines, Quest apps must be intuitive and polished. They must run at 72 frames per second a majority of the time, matching the headset’s 72hz refresh rate.

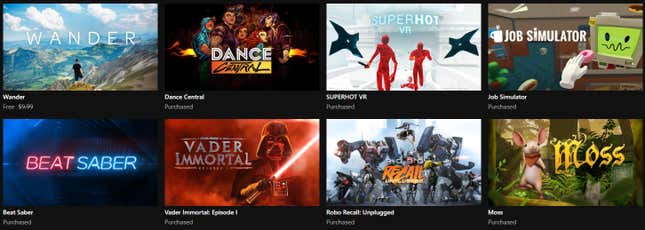

This means that Quest games, while not as robust as those for PC-powered headsets, run smoothly and comfortably. My time with Polyarc’s mouse adventure game Moss on the Quest has been much more satisfying that it was on the original Rift. It’s crisper, clearer and more stable. Playing Beat Saber (ducking and dodging obstacles as best one can in a wheelchair) is a joy, blazing fast and fluid. I’ve spent a ridiculous amount of time playing Angry Birds VR: Isle of Pigs, warping about each level to get the best angle with my bird slingshot to take out those porcine bastards

The same goes for more experiential virtual reality apps. National Geographic Explore VR, a launch title for the Quest, is one of the more impressive virtual reality learning experiences I’ve come across. Navigating Antarctica on foot or in a canoe, climbing the ice shelf, getting lost in a blizzard—it’s so good.

The downside to a curated store is that some popular virtual reality apps won’t make it to the Quest as readily as they do other VR platforms. I’m bummed I have to wait until August for virtual community AltspaceVR while the developers work to polish the program and bring it in line with Quest standards. But it also means I will be getting the best, most stable version of AltspaceVR. I won’t have to worry about purchasing a game or app only to find it’s a quick-and-dirty VR cash-in with little substance or sub-par technology implementation.

It feels like all hardware leading up to the Oculus Quest has been virtual reality’s beta testing stage, as engineers tried to figure out how best to deliver enjoyable simulated environments and experiences to the end user. Speaking to Stephen Totilo back in 2012, gaming wise man, Doom co-creator and current Oculus Chief Technical Officer John Carmark predicted that in a few years we’d see a wireless headset powered by mobile phone hardware that uses camera for optical positioning. This is exactly that. They lost the wires, stripped away the need for external cameras and got rid of the dependency on external hardware. Now all anyone needs to experience full-featured virtual reality is a bit of space and the Oculus Quest.