As a kid, I never liked Pikachu much, preferring the softer and squishier Jigglypuff or the catlike Eevee. I didn’t see the point in capturing a Pikachu. Pikachu was the mascot. Everyone loved Pikachu. I could save my love for someone else.

20 years later, I decided to try the “Nuzlocke Challenge” in Pokémon X. Pokémon is, generally speaking, not meant to make you anxious or upset, but long-time fans have always looked for ways to change things up. Enter the Nuzlocke Challenge. Originating from a comic of the same name, the challenge entails, most importantly, that every time a Pokémon faints, it ‘dies’ and you have to release it. To add more difficulty, other rules stipulate that you can only catch the first Pokémon you encounter in any area, and that you have to nickname every Pokémon, so you become attached to them. But it’s the idea that Pokémon can die at all suddenly raises the stakes.

When I first discovered the Challenge in 2010, it was through the comics from Pokémon fan artist Petty.

“Six years ago I was in my senior year of college when a friend of mine said we should try playing Pokémon, but with rules to make it harder,” Petty told me over email.

“I ended up reading a bunch of the comics done by users like Notepad, Robot7, Hale, Medody and Nuzlocke himself,” Petty said. “After reading them I thought, ‘This looks like fun! I should try doing one of these comics too.’”

She crafted a humorous, sometimes heartbreaking tale about their journey to the Elite Four. Every time one of her party members died, she’d make them a loving memorial.

As the challenge is emotionally and mechanically demanding, nuzlockers care about their Pokémon in a way that other players don’t. “As I played, I began to really care about whether Pokémon got hurt in battle and I got more and more nervous as they took damage or if I was going into a battle where I didn’t have type advantage,” Petty explained to me. The challenge is less about if you can beat the game, than if you can stand to watch the Pokémon you’ve grown to love leave you. When I started my Nuzlocke run, that was the experience I wanted in on.

Truthfully, even without Nuzlocke, I still found it easy to get attached to my party. I’d coo at the screen gently when my team did a good job, or curse them out when they did a bad one. Introducing the aspect of loss on top of that was guaranteed to make my brain short circuit, though I didn’t know it at the time.

When I started my journey, I picked Fennekin as my starter and named him Frank. The early game turned out to be easy, especially since I would sit in front of the TV to grind levels. Low-level wild Pokemon didn’t pose a problem.

I caught a Fletchling and called him Mark, and a Pidgey I named Ronald. They were the first two Pokémon I caught in the game, and they were a bit disappointing. Mark and Ronald, I am sorry to say, were redundant. You don’t need that many birds on your team, but I was stuck with them because of Nuzlocke’s iron-clad rules.

I was still fond of my team—especially Frank, who I’d always loved for being a cute little fox and a beastly a fire/psychic type—but in a normal game of Pokémon, I always end up trading up these early creatures for better, more exciting ones. In typical games, I would keep that Pidgey for when I needed to use Fly, sure, but otherwise? These guys were goners. There was a dark part of me that was already writing the narrative around their eventual deaths. Who would go first? Who would they lose to? Would I even care? I got bored with grinding fast and I was already leaning towards sacrificing Fletchling if I had to. Mark would have served me well, I’m sure, but getting the badge mattered more to me than the sparrow’s livelihood. To paraphrase an America’s Next Top Model contestant, this was not America’s Next Top Best Friend. I was there to win.

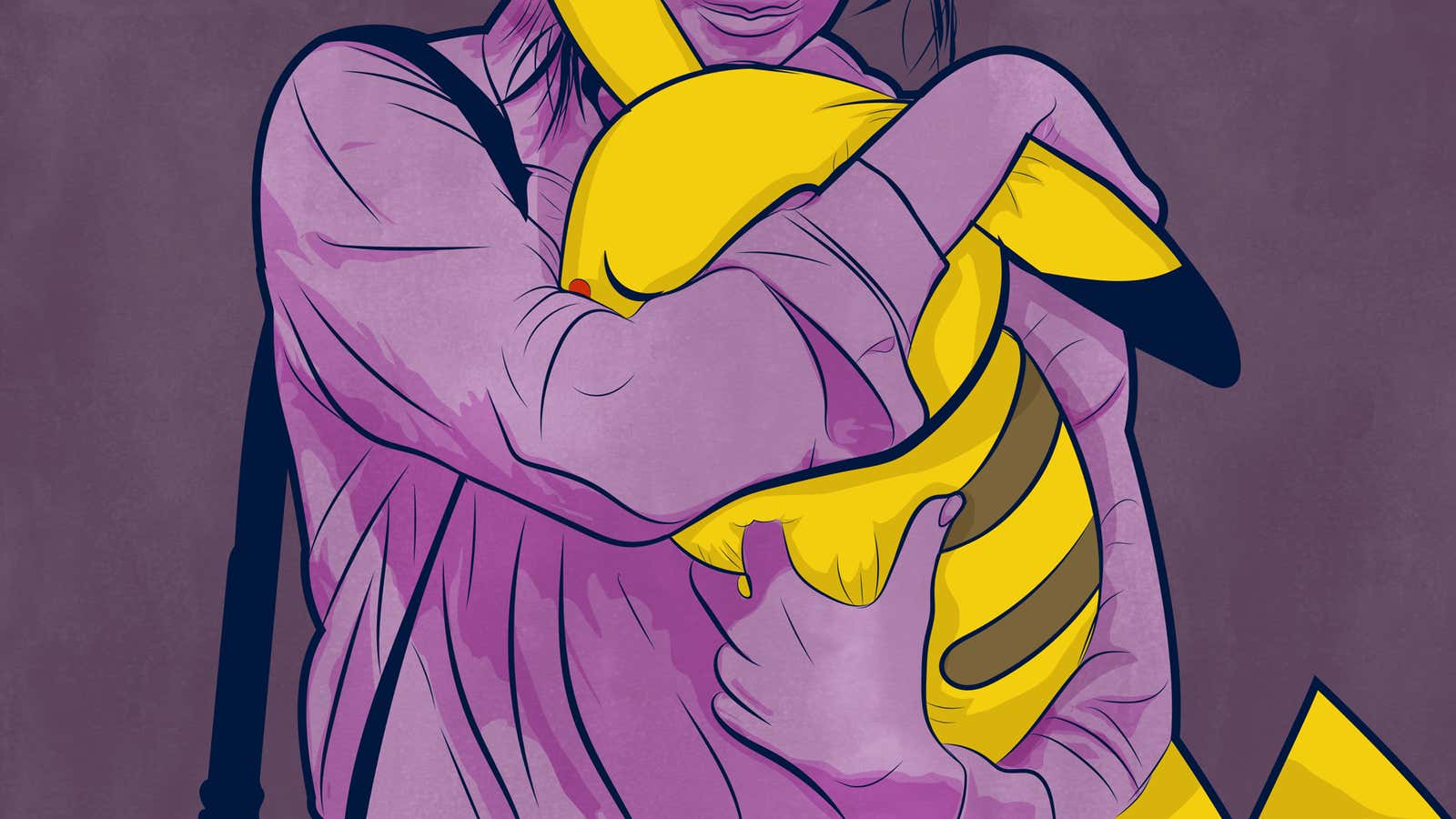

Mere minutes later, when I made it to Santalune Forest, I found a Pikachu. My stomach fluttered with excitement when I caught her, only to then fill with dread. I finally had a Pikachu of my own, and it was so adorable, so sweet, and so useful. Finally I had found something that wasn’t a dang bird and she could shoot lightning bolts to boot! I had to take her home. I named her Veronica, and I loved her very much.

When you play with a Pikachu in Pokémon-Amie, a minigame where you can pet, feed, and play with your Pokémon, they say, “Pika pika!” in the exact same intonation as the cartoon I watched as a child. If you pet them on the red patches on their cheeks, they’ll electrocute you briefly, grinning like a puppy. When I fed Veronica ‘Poke Puffs,’ I’d let them hover above her mouth, and she’d look up at them eagerly, lovingly. This was the game doing its job. Even as a person who never had pets, I felt a Pikachu-shaped twinge in my heart.

Veronica’s characteristic, as dictated by the game is “impetuous and silly.” She had standard moves like Thunderbolt, but also appropriately-named moves like ‘Nuzzle.’ Not only has Nuzzle been really useful in battle, but the idea of her snuggling up to the enemy warms my heart. I’ve kept Veronica as the active Pokémon in Pokémon-Amie, even though some of my monsters need affection too. It’s shameful, but every parent has their favorite kid.

Nuzlocke runs are hard because Pokémon are your precious children, and you’re supposed to protect them. Could I let Veronica take a hit in a battle where she didn’t have a type advantage? Would I allow her to sacrifice herself so I could get a precious gym badge? Could I even watch her get to low health?

Thanks to Veronica, the Nuzlocke challenge became a task for stronger hearts than mine.

Other trainers will go on to beat the Elite 4, but I am content to have my own Pikachu. And she’s never going to leave me.