Back in September 2021, The Museum of Art and Digital Entertainment in Oakland, California, better known as The MADE, began tweeting about how impossibly difficult it seemed to fund a video game museum.

The MADE’s tweets lamented a total lack of funding support from both federal grants and video game companies. Many potential donors apparently balked at the museum’s lack of an adequate physical space, even as that was exactly what it needed funding for. “We’re beginning to feel like we’ve been stuck in the tutorial for 10 years,” it wrote, “despite gaining 30 levels of experience.”

The tweets pointed to the organization’s 10 years of “working tirelessly” to raise funds, all in an attempt to build out a “bigger and better” space for its mission: preserving our digital heritage in playable form while inspiring the next generation of developers. That’s a tough task when you have little to no money.

Founded in 2011, The MADE got its start on the back of two successful Kickstarter campaigns—one in 2011 that raised $21,329 and another in 2015 that attracted $52,920—that allowed it to rent space in the San Francisco Bay Area. Neither location the nonprofit moved into was ideal. The last spot resembled a LAN party session, library, or retro games store more than an actual museum.

Despite this, The MADE still held events and taught classes to aspiring game developers in these tiny spaces, soon garnering the attention of two big-name Silicon Valley companies, Dolby and Google. Each has since sponsored the organization and supported its mission with generous annual donations of $10,000. But the yearly checks only last so long. The MADE is entirely volunteer-run, and raises the majority of its income through video game tournaments and ticket sales. So, money is critical, but it can be difficult to expand when you’re only ever breaking even.

The ongoing Covid pandemic has upended The MADE these last few years, forcing the nonprofit to close its physical space in Oakland and ask its supporters to appeal to groups like The Kapor Center and EA for sponsorships. Despite the generous donations from the likes of Dolby and Google, The MADE only barely breaks even every year. The seemingly never-ending scramble for funding hasn’t stopped the organization from aspiring to greater heights, but it has resulted in a pretty big change in leadership for the struggling nonprofit.

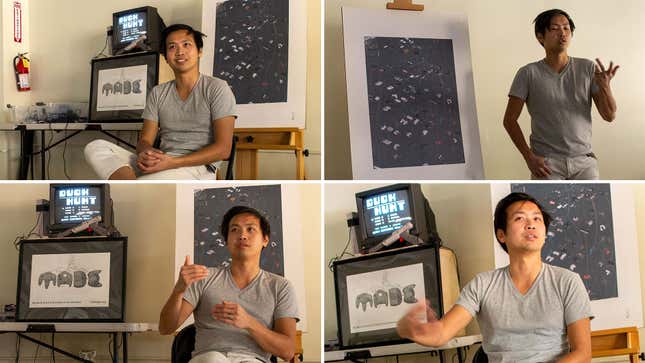

Not long after those frustrated tweets, the MADE’s founder and now former executive director, Alex Handy, handed over the museum’s reins to incoming executive director Shem Nguyen. Kotaku spoke to both about running a nonprofit video game museum, fundraising frustrations, and what the future has in store for The MADE—namely, the new space it’s moving into this June.

Talking to outgoing MADE executive director Alex Handy over video, his intense belief in the cultural importance of video games is evident. At different times he’s impassioned, frustrated, angry, even raises his voice as he recounts the many problems he’s encountered over a decade of trying to keep The MADE afloat.

Handy said he grew tired of “begging for money,” which became something of a “full-time job” for him by 2021. He felt wiped out by working a separate full-time gig on top of spearheading the game-preservation nonprofit, which required an inordinate amount of energy just by itself. But what grinded Handy’s gears most was how risk-averse the games industry had seemingly become, even toward charitable giving.

“As the tweet storm that inspired this story plainly points out, the issue is that everybody makes you do a dog-and-pony show,” Handy told Kotaku. “The rest of the industry [outside of Google and Dolby] has mostly [just] sent ‘stuff.’ We’ll get games. We’ll get old systems and computers. That’s wonderful. We need that stuff. But that’s the only button the industry knows how to push.”

Handy, who has been in the industry for 20 years and previously served as an editor at Computer Gaming World, a now-defunct magazine owned by IGN parent company Ziff Davis, has contacts inside a number of the biggest game companies. He knows people at Activision and EA, but they haven’t been too helpful.

He recalled one fundraising exchange he had in which, after drafting a “terrific intro” detailing how The MADE would utilize the money it was asking for to help preserve the venerable publisher’s heritage, an Activision contact dismissed Handy’s appeal with a curt reply, saying that the company “doesn’t do that.”

Instead what often happens, Handy said, is the large game companies will simply offer volunteers, when what The MADE really needs is tangibles. Money. Handy believes some companies do want to give to charities like this, but there are just too many hoops nonprofits have to jump through.

One of the hoops Handy called out was Benevity, a charitable donation-management start-up he says many companies in Silicon Valley use to dole out funds. It’s not that developers and publishers using the service is wrong or unhelpful, but forcing donations through this proprietary platform creates so many new “hoops” to jump through it would take a new, full-time staffer just to keep everything moving. (In reality, there is no such person.) Handy wishes companies would go back to giving more directly to charitable organizations instead of putting the onus on individual employees choosing (or more commonly, not choosing) to donate through Benevity or similar middleman entities.

It’s for this very reason, Handy said, that chasing grants is a waste of time. They’re helpful in certain specific circumstances, but chasing them requires mounting that constant “dog and pony show” that’s ultimately unsustainable. “Everything we do for grants is stuff we’re not doing to keep the doors open, the lights on, and the systems running,” said Handy. “And if you don’t get the grant, 100% of your time on it was wasted.”

That’s not to say The MADE has never gotten money before. Handy mentioned Dolby a number of times for being “a wonderful financial sponsor” that’s focused on how its money impacts a community. He just wishes game studios would step up and be similarly intentional with their giving, especially considering how many start-ups pop up in Silicon Valley.

“When I look around the Bay Area, dropping a million dollars on a couple of chuckleheads in a basement with an algorithm happens every five minutes,” Handy said. “That’s sort of my frustration here, is that somebody should saddle up and put their name right in front of the [this] museum’s name, right? You could be like, ‘This is the Electronic Arts Museum of Art and Digital Entertainment and we put up the money and we’ve got this big EA section over here.’ It could be Activision or Nintendo or Ubisoft.”

But throughout his decade-long tenure, Handy couldn’t manage to secure a physical space that would’ve allowed The MADE to look like the true museum it aspires to be instead of, as he put it, “looking like somebody’s basement with $100 couches because we replaced the last $100 couches that died two months ago.”

Handy says that the scrappy appearance of The MADE’s incarnations to date has been a major reason many of the biggest video game publishers have ducked out of its fundraising efforts. They wanted to see a “real space.” It didn’t matter that the organization had 10 years of history to its name, that it’s been mostly self-funded through in-house events and game development classes, or even that The MADE has been single-handedly maintaining LucasArts’ Habitat—the first-ever massively multiplayer online role-playing game from the ‘80s, that’s still playable to this day via browser—at no charge.

All of this proved both The MADE’s legitimacy and its seriousness, but without an adequate space, Handy said the opportunities for more substantial funding partnerships never seemed to materialize. It’s unfortunate, because as Handy puts it, “The public needs, wants, and loves to interact with this stuff.” Not to mention the importance of preservation and education.

Despite the many hurdles Handy encountered throughout his 10 years spearheading The MADE, he’s confident the organization will ultimately pull through. In fact, when speaking about the new executive director Shem Nguyen, Handy said no one’s better positioned to lead The MADE toward not just the new space it recently secured, but greater success in the future.

Shem Nguyen’s first encounter with The MADE came through a co-working event it hosted in 2015. A Vietnamese-American who grew up programming in the general-purpose language BASIC, Nguyen told Kotaku he began volunteering his time and teaching classes on game development at the nonprofit after spending time in the game industry himself, first as a Lucasfilm / ILM staffer, then as an indie VR developer.

The project he was working on didn’t pan out, but The MADE served as a source of motivation for him to stay the course of game development. This led to Nguyen collaborating closely with Handy and the rest of the org’s education team to teach classes. Once the pandemic hit, though, Nguyen said he got really involved with The MADE, teaching and volunteering like crazy before Handy asked him to take over the executive director role.

“[Nguyen] came to The MADE through education as a teacher, so he has exactly the perspective on the MADE that I wanted,” said Handy. “Shem knows that The MADE is about preservation and most importantly, about education. That’s super important to me. I know he will always focus on education, always keep the classes free, and above all, he’ll be way better at running this thing than I ever was.”

Speaking to Kotaku, Nguyen agreed with his predecessor that “fundraising for [a video game museum] is extremely hard,” but added that he doesn’t think The MADE has done a good enough job at selling prospective donors on the value of its 10-years-and-counting of archival and community-based work.

“It’s really on me to prove that this money you’re putting into the nonprofit, as either an Oakland resident or a person who believes games are an art form, will be used to do a good job,” said Nguyen. “I think that any museum should always feel like you’re walking into a gift full of history that’s been passed down to you or knowledge bestowed upon you in a classroom. Now it’s my job to kind of show people [who are giving us money] this history. So, it’s like, ‘How do I expand upon that gift?’”

Alongside the more technical side of running a nonprofit, including honing his grant-writing skills, Nguyen said he wants to help show how The MADE provides value for Oakland residents. He’s already partnered with local organizations, such as the Oakland Vietnamese Chamber of Commerce, to host events and teach classes. He’s also immersed himself in the nonprofit sector, befriending social justice activists like Dr. Jennifer K. Tran, an assistant professor at CSU East Bay and executive director of the Oakland Vietnamese Chamber of Commerce. All of this, Nguyen hopes, will help the games industry see The MADE as a serious organization worth giving money to.

“We would like some support from technology companies and from people who work in [the games industry],” Nguyen said. “Companies that really pride themselves on being part of this heritage. If there’s some way they could help out financially, then we could do the work our institution is meant to do, which is preservation.”

Despite the many challenges, Nguyen continues to believe in The MADE’s “superpowers,” pointing to achievements like its ongoing stewardship of LucasArts’ Habitat as a demonstration of his small nonprofit’s ability to punch above its weight.

Nguyen’s confidence wasn’t unfounded. After The MADE’s long, multi-year struggle to secure a new location, it finally succeeded. On April 26 a tweet revealed that The MADE is moving into an approximately 4200-square-foot spot in Swan’s Market at 921 Washington Street in Old Oakland. A grand opening celebration is planned for June 10.

The space originally belonged to biotechnology company Ginkgo Bioworks, which moved earlier this year. Thanks to Nguyen’s contacts in the nonprofit sector, he was able to scoop it up as the new home base for The MADE. There was a mix of emotions when signing the lease, Nguyen said, but he’s “really thankful” for all the organizations and volunteers who’ve donated their money and time.

One of the biggest donors was, once again, Dolby. Nguyen didn’t specify how much the audio technology giant gave to The MADE this time around, but he said it’s consistently been “one of the only companies to really step up” and show support. You can expect to see Dolby’s name around the museum when it reopens in June because of “the impact its gift is making,” Nguyen said. At the end of the day, though, whether the organization has a physical space or not, the real challenge for The MADE will always be money.

“We need money to reopen,” Nguyen said. “We currently have zero paid employees. Everyone’s here because we believe digital history should not be the exclusive domain of those with money or with parents who worked in technology. We’re driven by the understanding that this heritage belongs to all of us. The MADE needs the funds to do the history of video games justice, hire employees to keep the place running, and pay for the space and the associated utilities. […] If we are to understand the future, we must all have a place to go to understand the past, and this is precisely what The MADE has been for the past 10 years and will continue to be for decades into the future.”

Former executive director Handy echoed the sentiment, saying he’ll support Nguyen however he can—including “going out and getting money.” But whether the dollars are there for the museum to expand with “nice furniture and quality installations” or not, Handy said The MADE’s game preservation work won’t end that easily.

“I don’t want to sound like we’re angry or bitter,” Handy said. “[It’s just that] the system isn’t really set up to deal with something like us and has never seen anything like us. We’re never going to close. We’re never going to stop. We’re always going to be here no matter what happens.”

You can give money directly to The MADE via its donation portal or, if you work at a tech company, through Benevity. You can also volunteer at The MADE or ask about sponsorship opportunities, becoming a partner, and corporate memberships.