Though HBO’s The Last of Us largely preserves the story and lore of the original game, it rarely seems interested in adapting the actual things most players spend time doing when playing The Last of Us. In prioritizing the game’s narrative over depicting specific gameplay mechanics, there’s a tension told through the original’s button-actuated action that feels unrealized in the show. Television is non-interactive and it very much seems that the creative goals of this show were to focus strictly on the characters and general plot, avoiding what might’ve been seen as gimmicks in order to achieve a more culturally acceptable “prestige” kind of storytelling. But without recreations of certain scenes and an unwillingness to try and adapt the story the game tells through the objects in its world and the gritty, brutal resourcefulness its characters must rely on to survive, an entire side of The Last of Us just isn’t present. The story was adapted, but not necessarily the game.

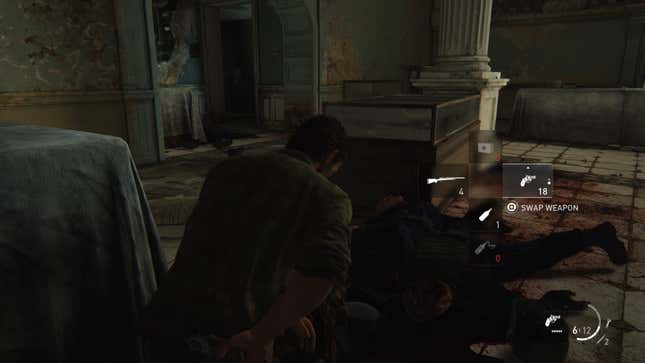

The Last of Us video game certainly falls under the category of “action game,” but does so through a survival-horror lens which dramatically slows that action to a crawl. When the tension is high, particularly during combat encounters, every footstep traveled, bullet loaded, and decision made is done under threat of death and failure. The Last of Us requires players to not only think quickly with what items and weapons they have on hand, but what they could hypothetically acquire by means of a relatively quick, in-the-moment crafting system that sees Joel and Ellie make use of bottles, rags, gunpowder, sharp objects, and the like.

But unlike other adaptations of video games, such as Paramount’s Halo TV show, The Last of Us seems very uninterested in the story the original told through its gritty gameplay. Maybe that’s its secret sauce so far, but maybe it’s also a missed opportunity: Games tell entire stories through what you do, not just what you see and hear.

It wasn’t until the second episode that something on screen triggered a reaction I was very familiar with from countless hours spent playing The Last of Us: The pressure and anxiety of painfully reloading a revolver, one damn bullet at a time while a murderous creature is breathing down your neck. And still, it was fleeting, and the show doesn’t feel like it wants to dwell there too long.

Read More: The Last Of Us’ Second Episode Ends In Tragedy

This happens in a scene that directly parallels events in the game: Ellie, Joel, and Tess must move through an old, abandoned museum filled with clickers. As in the game’s lore, these are humans in an advanced stage of infection who can no longer see but instead roam about while making, you guessed it, clicking sounds that provide some kind of echolocation.

In this scene, Joel hides out of direct view of a clicker, holding a flashlight between his head and left shoulder. He cautiously empties the spent bullets into his hand. Given that we just observed a clicker take notice of the group after a quiet gasp from Ellie, it’s clear that one dropped piece of metal would be a lethal mistake. Joel slips the empty bullets into his left pocket before fishing out new bullets from his right. It feels clunky, dangerous, tense. And to anyone who’s played the game, it feels familiar.

As I watched, I caught myself saying—as I do when playing the game and am out of ammo—“Christ, load the fucking gun, please.” The tension I felt here was nearly tactile, because I’ve been trained to respond to, not just watch, this kind of tension with a similar awkward struggle that Joel has on screen both times. But I’m sure this moment translated to those who haven’t played the game, either. You likely felt the “reload, reload, please reload” urge in your very soul.

In the game, your character (usually Joel) navigates their inventory with presses of the directional pad and different face buttons depending on what you’re trying to do. This abstracts what it’s like to dig through your backpack or pockets. Though you can improve the speed at which you craft or equip weapons, this tension is pretty central to the horror and action, and it’s hard to imagine the game without it. Aside from the scene I just mentioned, and one moment in a later episode when it seems like the camera moves to a quasi over-the-shoulder perspective while Joel fires a weapon, the show usually sticks to standard prestige TV framing of its action and zombie drama.

Consider the way action was portrayed in the television adaptation of the first-person shooter Halo. (Let’s ignore all dramatic departures that series makes from its lore and the very, uh, weird things that happened narratively; they’re not the point right now. I want to explicitly highlight how the show adapts the story told through Halo’s gameplay.) Not only does the camera sometimes literally pivot to a first-person perspective, but even the action we see on-screen matches what we do in the game.

This made for some of Halo the show’s best moments: Characters toss grenades before running into a foe, bouncing it into enemies to lower their shields and finish the job just as we do in the game. Fall damage isn’t a thing, as we see Master Chief and other spartans jump down to a planet from orbit with no issue; pulling this off in a Halo game often feels very empowering, and so too do these action scenes. Even the relatively high jump height of Halo game characters is communicated during these action sequences. The show often looks how the game plays, when it could’ve just offered standard TV gun action.

Even if you’ve never played a Halo game, the super-soldier fantasy of the action is likely communicated well on-screen. And if you have played any of the games, it feels familiar. Halo the TV show was interested in telling a very different sequence of events with its world and lore, but it was quite committed to translating the action we know from the games into the new medium.

In The Last of Us, the absence of similar scenes changes the tension present in the source material. The classic “mash the square button to break the glass” sequence early on in the game after Joel and Tommy’s pickup truck flips during the outbreak is one such example. The dilemma of needing to get out but also not necessarily wanting to get out there with all the zombies is central to that scene. With repeated hits of the glass as the transitory moment, the impending rupture of violence into more violence, we’re on the edge of our seats, often mashing the button. The show doesn’t replicate this feeling, it doesn’t adapt this feeling. In the show, Joel just grabs Sarah and leaves the truck. Similar moments of intense gameplay, which require the mashing of buttons or accurate aim, are a matter of life or death; but this isn’t totally translated into the TV show. A later action scene that provides one of the game’s most striking and desperate images is also strangely absent from the series.

But it’s not only the action that’s being portrayed in a different way. The very objects used to craft things, the act of crafting, and the level of resourcefulness these characters have had to develop in this fallen world aren’t really represented or conveyed in the TV show. The Last of Us’s game objects, in their crude, crafted, out-of-time place and use, are important to the tone of the game.

Just as the show’s and game’s infected human beings bear a warped resemblance to their former selves, so too does the environment of The Last of Us feel like a sad echo of the world that once was. Objects once designed for other purposes must now be reconsidered, used in crafting, or moved to navigate a terrain that was once open to humans, but now presents obstacles. Objects once made for a completely different use must be repurposed for last-minute survival. A brick in The Last of Us goes from being an object and symbol of construction to one of destruction as you use it to smash open a clicker’s head, the brick crumbling to dust as you do.

Desperation might be conveyed in the show by a character grabbing a random pipe to wield, but the barbarism and complete out-of-time feeling of wielding a baseball bat with scissors tapped around it—a standard crafted weapon in the game—never happens here. No one grabs a used cola bottle and some rags to make a serviceable-yet-flawed silencer. The jarring reality of seeing objects torn from their pre-outbreak use and how people have had to develop radically different relationships with the physical world just isn’t in the show. Beyond the characters’ emotional states, this was a key component to conveying the desperation, brutality, and need for survival in The Last of Us’ world. Players develop an instinctive reflex to “look for supplies” when entering a room. The need to quickly adapt, deploy various MacGyverisms, and survive is a part of the story of The Last of Us, though the TV show largely ignores this.

The Last of Us is a pretty good, entertaining TV show that has genuine moments of greatness. But given how cinematic the game already was, and how the show largely just revises those scenes, it almost feels as impressive as an acoustic rendition of Metallica’s “Nothing Else Matters;” worthy of note if done particularly well, but it was halfway there in the original already. The Last of Us wants to claim the prize as finally breaking the curse of video game adaptations, but if it gets there, it will have done so without adapting the actual game part of the video game.