There have always been slight regional differences between consoles, but when the Nintendo Entertainment System hit store shelves in the fall of 1985 it had been stripped of nearly all the form and charm of its Japanese counterpart. It was clear that Nintendo didn’t want the NES to be seen as a cheery “family computer,” but rather a hulking grey gaming VCR from the not-so-distant future.

The Famicom was significantly smaller than the NES, as were its colorful cartridges. The curvy crimson and white gaming machine came bundled with two controllers, both of which were permanently tethered to the back of the system via short black cords. The attached controllers could even be stored on the Famicom itself, wedging snugly into shallow grooves on either side of the console deck. It was here, cradled to the right of the cartridge slot, that Japanese players could find the most unique feature the Famicom had to offer: a tiny, built-in microphone.

The Famicom microphone, which replaced the start and select buttons on the console’s second controller, is a classic example of Nintendo’s long running reputation for introducing gaming gimmicks that are simultaneously innovative and absurd. During the NES era it was accessories like R.O.B. the Robot and the infamous Power Glove, and today it’s titles like Nintendo Labo and Ring Fit Adventure.

Added by Nintendo research and development head Masayuki Uemura, the second player microphone was hardly the console’s main draw. The Famicom was Nintendo’s second home console in Japan (following the Color TV-Game line) and the company’s introduction of first- and third-party swap-and-play cartridges was easily the system’s biggest selling point. Nintendo wasn’t trying to hide the existence of their quirky new sound receiver, but it was rarely mentioned in early print and TV advertisements.

Despite its availability to developers at launch, the second player microphone was only implemented in a dozen or so of the 1,000+ games released during the Famicom’s staggering 20-year lifespan. Even more surprising was the fact that when the microphone was put to good use it was rarely to benefit players in a secondary role. Instead, the microphone usually took on the form of a gateway to easter eggs in single player games. Most times this information could be found within a game’s manual, where it would subtly allude to attacks and secrets that could only be triggered by sound.

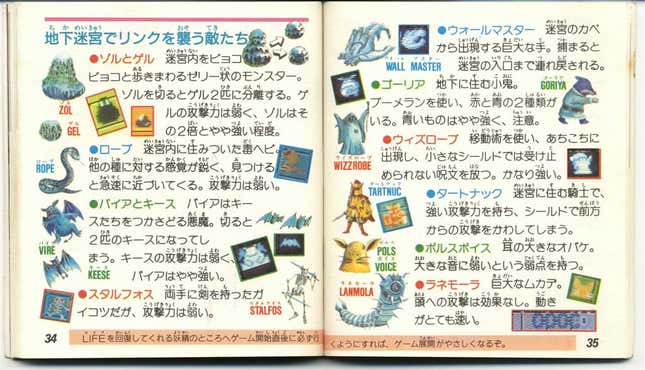

The most well-known of these easter eggs (it’s a secret to everyone) involves the enemy Pols Voice from the original Zelda no Densetsu - The Hyrule Fantasy, released in Japan for the Famicom’s Disk System add-on in 1986. In the game, Pols Voice are depicted as ghostly rodents with enormous ears, usually found scurrying about dungeons in packs of three to five. The Japanese instruction manual for Zelda, which detailed many of the game’s enemies, mentioned that the creatures “hate loud noises.”

I’m sure you can guess the rest.

With a mighty roar into the second player microphone, adventurers could eradicate any Pols Voice on screen. This method was much preferred to attacking with normal weapons, as each Pols Voice took multiple hits to defeat.

Oddly, this hint about Pols Voice aversion to noise was also added to the instruction manual for the NES version of The Legend of Zelda. Knowing international players couldn’t rely on a microphone, designers had tweaked the game to make Pols Voice weak against arrows, but it seems they forgot to pass this bit of important information on to the localization team handling the manual.

Another classic secret hidden behind the Famicom’s microphone could be found within Hikari Shinwa - Palutena no Kagami, better known in the western world as Kid Icarus. While perusing the wares in one of the game’s many shops, players could hold down the A button on the second controller and speak into the microphone to haggle with the shopkeeper.

As it turns out, Palutena no Kagami didn’t actually know what players had murmured into their controller, just that something had been said at all. With this in mind, it was soon discovered that players could finagle rock-bottom prices by simply blowing as hard as possible into the microphone, as the shopkeeper seemed to very much enjoy the excessive amount of sound involved.

I highly recommend trying this method of bargaining the next time you visit your local farmers market. If you’re not completely satisfied with the price of your items, trying leaning in and blowing on the seller’s face. They’re sure to drop their prices immediately. Or pop you in the chops. You’ll just have to find out.

Of course, it’s nearly impossible to bring up the Famicom’s microphone without mentioning the notorious Takeshi no Chōsenjō, otherwise known as Takeshi’s Challenge. This bizarrely dark and painstakingly difficult game allowed players to drink themselves silly, divorce their wife, and brawl with everyday townsfolk. Takeshi’s Challenge also produced a pair of commercials featuring the titular comedian sitting glumly amidst piles of broken electronics. In the commercials Takeshi can be seen yelling into the Famicom microphone to bring up a map, as well as singing a snippet of karaoke to raise his spirits. Both verbal cues were intended to be hints for those brave or foolish enough to embark on Takeshi’s convoluted adventure.

As many know, Nintendo’s wacky microphone legacy didn’t end with the Famicom, or stay contained to Japan. Games like Hey You, Pikachu! for the Nintendo 64 and Odama for the GameCube reintroduced the concept of shouting one’s way to victory to new generations of mildly confused children. Microphones were added to Nintendo handhelds such as the DS and 3DS, where they played important roles in series such as WarioWare, Brain Age, and Nintendogs. Pols Voice even made their triumphant return in The Legend of Zelda: Phantom Hourglass, where international players could finally destroy the whiskered blobs as intended—with a deafening shriek.

With the announcement of the wildly popular Nintendo Classic Mini: Family Computer in 2018, many speculated as to whether the retro console would go so far as to include the iconic microphone. Sadly, the miniature system forwent the real deal, settling instead for a convincing sticker. Though, to be fair, the Classic Mini only featured one game (Zelda) that could have used the microphone at all.

Most recently, the Famicom controllers have been featured as special edition Joy-Cons, sold in limited quantities to Nintendo Switch Online subscribers in Japan. This time around Nintendo didn’t cut any corners, imbuing the second controller with a legitimate microphone for use with the Switch’s online library of Famicom titles. It seems a bit backwards that the only official controller for the Switch with a working microphone is the one modeled after a design from 1983, but hey, that’s Nintendo for you.

We may never know why Masayuki Uemura felt a microphone was a worthwhile addition to the Famicom, or why it was deemed unfit for audiences outside Japan, but it will forever stand as a funny footnote in gaming history, one that truly embodies the unique silliness of the Nintendo brand.

If you’d like to hear more about the Famicom’s built-in microphone, as well as some other interesting bits of gaming history, I invite you to check out the newest episode of the Memory Card podcast.