When discussing Nintendo’s rise as a digital dreamsmith in the ‘80s, game designers like Shigeru Miyamoto and Gunpei Yokoi get most of the limelight. But it was the hardware designed by Masayuki Uemura that served up their fantasies to millions around the globe.

I spent 2019 criss-crossing Japan researching my book Pure Invention: How Japan’s Pop Culture Conquered the World, in search of the country’s architects of cool. In March of that year I came face-to-face with a true legend: Masayuki Uemura, the engineer who designed Nintendo’s first cartridge-based game system, the Family Computer, aka the Famicom, aka the Nintendo Entertainment System.

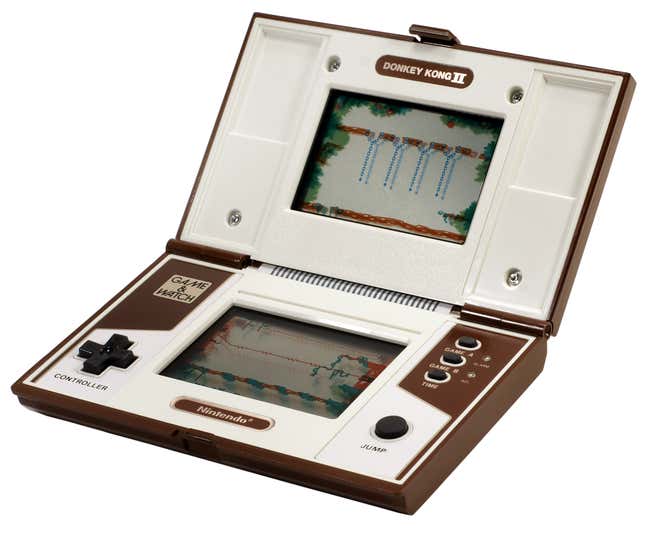

With a design based on the arcade hardware that powered Donkey Kong, the Famicom quickly revolutionized home gaming in Japan when it was released in 1983. As the NES, it revitalized the home video game market in the United States after the Atari market crashed. From then on, it proceeded to deliver a steady stream of Japanese fantasies into the hearts and minds of people around the world. It’s hard to imagine a world today without Uemura’s machine.

Masayuki Uemura joined Nintendo in 1972. Gunpei Yokoi, the inventor and toy designer whose products like the Ultra Hand had transformed Nintendo from a humble maker of hanafuda, Japanese playing cards, into a well-known toy and game company, recruited Uemura away from his previous employer, the electronics company Hayakawa Electric, known today as Sharp. Uemura retired from Nintendo in 2004, and currently serves as the director for the Center for Game Studies at Ritsumeikan University in Kyoto. The university’s leaf-covered Kinugasa campus is a quiet oasis in what is—or was, before COVID-19—a bustling and tourist-packed city. It is also a 10-minute walk from the ancient Zen rock garden of Ryoan-ji temple, whose evocatively arranged boulders and artfully raked gravel seem to me one of Japan’s earliest “virtual realities.”

Departments that teach students how to make video games abound in higher education today, but the Ritsumeikan Center for Game Studies is one of only a handful of academic efforts specifically designed to preserve home video gaming equipment and ephemera. Its archives contain everything from early home versions of Pong to the latest consoles, every controller variation under the sun, and an ever-expanding library of software on tapes, cartridges, and discs. The packed shelves of its climate-controlled storage facility look like something out of a kid’s dream, organized with the obsessive rigor of the Library of Congress. The scent in the air is that paper from countless magazines and strategy guides, tinged with the nostalgic ozone smell of vintage electronics.

Uemura was 75 years old at the time of our interview, but seemed much younger. A benefit of a life spent making playthings for the world? Whatever the case, there is no mistaking the amusement and restless curiosity in Uemura’s eyes as we sit down over a round of Famicom Donkey Kong to talk about the little beige and burgundy machine that touched so many lives.

Kotaku: What was Nintendo like when you joined the company?

Masayuki Uemura: One of the things that surprised me when I moved from Sharp to Nintendo was that, while they didn’t have a development division, they had this kind of development warehouse full of toys, almost all of them American.

Kotaku: What were your impressions of Nintendo’s former president Hiroshi Yamauchi, who ran the firm from 1949 to 2002?

Uemura: He loved hanafuda and card games. I remember once, early on, a birthday party for an employee and he showed up and got right into hanafuda with everyone.

He was a Kyotoite. It’s a city with a lot of long-running businesses, some maybe five or even six hundred years old. In the hierarchy of the city, traditional craftspeople rank at the top. Nintendo, as a purveyor of playthings like hanafuda or Western playing cards, originally ranked down at the very bottom. Doing business in that environment made him very open to new ventures. He wasn’t interested in specializing. He was keenly interested in new trends.

Here’s an example of what I mean. In 1978, he bought around 10 tabletop versions of Space Invaders and placed them in headquarters and our factory. The idea was that we’d playtest them as a form of research. But what ended up happening was the entire company got so obsessed playing it that we couldn’t get a turn in. It was like a fever. Everyone abandoned their posts and stopped working. I was just bummed out that we hadn’t made it ourselves. Shocked and annoyed [laughs].

Kotaku: Did you feel behind the curve compared to other game companies back then?

Uemura: In the 70s, we had no idea what was going on with companies like Namco or Atari because we were here in Kyoto. If you lived in Tokyo, you’d probably pick up lots of things about companies like Taito or Sega or Namco or even what was happening in America. But none of that filtered down to Kyoto at all. That’s Kyoto for you—a little standoffish, going its own way, and proud of it. To a certain degree, not even caring about the outside world. A little conservative when it comes to new things. When I worked for Sharp, I took many business trips to Tokyo. But when I started working for Nintendo, that completely stopped. It’s pretty shocking when I think back on it, but Kyoto has always been kind of closed off that way. So no, there wasn’t any sense of us being behind.

Kotaku: I’ve heard that the atmosphere inside the company was very competitive, with a big rivalry between Nintendo’s two R&D divisions.

Uemura: There wasn’t really any R&D 1 and 2! It was just Yokoi and Uemura. There wasn’t any rivalry! Yokoi found me and recruited me to Nintendo; he was my senpai. It was Yamauchi who set us up as rivals. It was symbolic, which is important in any corporate organization. That’s why he created R&D 1 and 2.

Kotaku: How did the Famicom project come about?

Uemura: It started with a phone call in 1981. President Yamauchi told me to make a video game system, one that could play games on cartridges. He always liked to call me after he’d had a few drinks, so I didn’t think much of it. I just said, “Sure thing, boss,” and hung up. It wasn’t until the next morning when he came up to me, sober, and said, “That thing we talked about—you’re on it?” that it hit me: He was serious.

Kotaku: Were you influenced by other companies’ machines?

Uemura: No. I mean, after I got the order I bought every single one, took them apart, analyzed them piece by piece. I looked at the chipsets, saw what CPUs they used, checked out the patents, all of it. That took about six months. Most of it I did myself, but I did have some help from outside resources, people who worked at semiconductor companies. I looked into Atari’s [2600] machine, of course—it was the biggest—and the Magnavox machine. Because those two were the biggest hits, and Atari’s biggest of all.

Kotaku: How did you analyze rivals’ game consoles?

Uemura: I had a semiconductor manufacturer dissolve the plastic covering on the chips to expose the wiring underneath. I took pictures, blew them up, and looked at the circuitry to understand it. I had some experience with arcade games, and right away I knew that none of what I was looking at would be any help in designing a new home system. They simply didn’t have expressive enough graphics. They had a monopoly on patents for them, circuit structures and features such as scrolling. And they were simply old-fashioned. That’s why I couldn’t use anything from them.

Kotaku: Did America’s game industry crash scare you?

Uemura: Japan didn’t really experience a video game industry crash like America did. What we had was an LCD game crash. They stopped selling at right around the same time—Christmas of 1983.

Kotaku: In US the crash made the very concept of games taboo in the industry for a while. What about Japan?

Uemura: In Japan, the issue was that toy stores didn’t know how to carry them. Toy stores didn’t carry televisions. So they didn’t see game systems as things they should carry, either. That’s why a lot of companies tried positioning their products as educational products, with keyboards, more like PCs than game systems. The thinking in the industry was that was the only way to go, back then. The only way to sell a video game was showing it on a screen, and it was a big ask of toy stores, making them purchase TVs. LCD games had their own screens; you could just put them out and they’d sell themselves.

Kotaku: Is that why you chose to style the Famicom more like a toy?

Uemura: It was less of a choice and more that this was the way it had to be.

Kotaku: Why is that?

Uemura: Because that was the cheapest way to do it [laughs]. The colors were based on a scarf Yamauchi liked. True story. There was also a product from a company called DX Antenna, a set-top TV antenna, that used the color scheme. I recall riding with Yamauchi on the Hanshin expressway outside of Osaka and seeing a billboard for it, and Yamauchi saying, “That’s it! Those are our colors!” Just like the scarf. We’d struggled with the color scheme. We knew what the shape would be, but couldn’t figure out what colors to make it. Then the DX Antenna’s colors decided it. So while it ended up looking very toy-like, that wasn’t the intent. The idea was making it stand out.

Kotaku: And it did. Were you surprised when it became a societal phenomenon?

Uemura: I didn’t have time to be surprised! When it really took off, I was totally focused on making the NES for the American market, and also on making the Disk System. I had my hands full. And we were swamped with defective returns. At first we had a very high percentage of defective machines being returned to us. We were just getting so many returns, far more than anything we’d ever seen before. That’s when I realized just how many people out there were playing with them; there hadn’t ever been a system this popular before. That was about the time Super Mario Bros. came out, 1985. Everyone in the company realized we were going to be swamped. Super Mario was fuel on the fire of the fad.

Kotaku: Mario arguably became even more of a phenomenon than the Famicom itself.

Uemura: Super Mario Bros. was the first to really bring a kawaii perspective to game characters. Actually, Donkey Kong was first to do it, in the arcades, and it established that unique sense of design. Until that point, most games followed the arcade style of shooting game design. Super Mario is often cited as the very first game to connect that style of cute character and cute music together. I’m not sure who specifically on Miyamoto’s team connected the dots, but that’s what happened. Probably Miyamoto himself.

Kotaku: After Nintendo went from 3rd or 4th place to 1st in the ‘80s, was there a sense things changed, among people inside the company?

Uemura: No! We’re in Kyoto [laughs].

Well, my salary went up. That’s a fact. So I was getting paid more, but the flip side was my job got a lot harder. President Yamauchi’s attitude played a big part in this, but my feeling was one of “seize the day.” Just go for it. You have to remember, there was a time, after Donkey Kong, that we really didn’t make another game for about two years. Well, not exactly, but pretty much. That’s the period Super Mario Bros. was being developed. That game basically ended up including everything and the kitchen sink, gameplay-wise.

Kotaku: What led to the decision to export the Famicom abroad?

Uemura: There’s a rule in the game industry that fads last for three years. That’s why President Yamauchi targeted America—to get around that. The prevailing sense at the time was that television games would fade into history as they were replaced by personal computers. So we were shocked that the fad kept going. It was Kudo-san, the president of a company named Hudson, one of the Famicom’s first licensees, who said to Yamauchi, “this is a culture.” Yamauchi was like, “What are you talking about?”

Kotaku: Japanese games swept the globe starting in the late 70s: Space Invaders, Pac-Man, Donkey Kong. Why do you think this made-in-Japan culture resonated with people all over the world?

Uemura: Actually, that’s what I want to ask you [laughs].

Super Mario Bros. isn’t set in Japan, but the character’s Japanese. The name Mario sounds Italian, but he isn’t Italian. They were really able to capture that ambiguity. The number of dots you could use to draw the characters was extremely limited, so Miyamoto was forced to use colors to differentiate them. He spent a lot of time working on the colors. In the end, it became the template for how a designer might express themselves through a game. It was a whole new world.

Until video games became able to portray characters, they were nothing more than strategy games like shogi or chess. Once hardware developed to the point where you could actually draw characters, designers had to figure out what to make. Subconsciously they turned to things they’d absorbed from anime and manga. We were sort of blessed in the sense that foreigners hadn’t seen the things we were basing our ideas on.

Matt Alt (@Matt_Alt) is a Tokyo-based writer, translator, and game localizer. He is the author of Pure Invention: How Japan’s Pop Culture Conquered the World, coming 2020 from Crown Publishing.