On March 25, 2015, the weather in Bellevue, Washington was just warming up enough to play hacky sack, a favorite activity of the employees at the game development studio Her Interactive. That morning, they had something more pressing to think about, though: they couldn’t log into their computers. Server problems, some reasoned. They were confused, yet calm. “But Penny [Milliken, CEO] had booked the conference room downstairs, and there was an HR person we’d never seen there before,” said an employee who was there. “One person went down at a time, and every time they came back up, they’d start packing up their boxes.” At the end of the day, 13 employees—over half the company—no longer had jobs.

This came as a shock, since many of Her Interactive’s employees had worked there for a decade or longer. Since its founding in 1995, Her Interactive had released 38 games, most of them based on the mega-popular mystery series Nancy Drew. The games featured Nancy herself solving puzzles and untangling mysteries by finding clues and investigating suspects. Since 2001, the studio had stuck to a strict production schedule, releasing two Nancy Drew games per year, and a couple months later, the studio was due to release its next one, Sea of Darkness. The Nancy Drew mystery titles had become a constant in the lives of both the developers and the fans. “We were all very invested in the game and in our fans,” said another staff member who was laid off. “[Her Interactive] really did feel like a family.”

But March 25, 2015 marked the moment that the once-predictable studio began to grind to a halt. Over three years later, Her Interactive still hasn’t released its long-delayed next game, Midnight in Salem, despite the studio’s repeated promises. The company’s relationships with the fans has deteriorated. The staff has dwindled even further.

This account is based on interviews with six former Her Interactive employees, some of whom spoke anonymously in the interest of protecting their careers, as well as an interview with Lani Minella, the longtime voice of Nancy Drew in the games.

The story of Her Interactive is that of a warning. It’s about a company that hit on an exciting game concept and rode that concept for nearly two decades, but then realized that its games were no longer as sharp and inviting as they’d been in 1999. Financial hardship paired with apparent mismanagement whittled away at Her Interactive until it became what it is today: a studio that is, at best, a shell of its former self.

When reached by Kotaku for comment on this story, Her Interactive provided its director of marketing, Jared Nieuwenhuis, for a phone interview. Nieuwenhuis said Midnight in Salem was still in development and still scheduled for release in 2019. He also explained the company’s silence over the past three years. “It’s not our intention to withhold information or become less communicative with our fans,” he said. “It’s just that when everything’s on the table and you’re reevaluating development of games and games in the past, it becomes very difficult to share certain things that might not become reality farther down the line.”

But for those of us who grew up playing the Nancy Drew games, Her Interactive’s disappearing act wasn’t just confusing. It was unnerving.

When I was about eight years old and my sister was seven, our parents got us a Nancy Drew game.

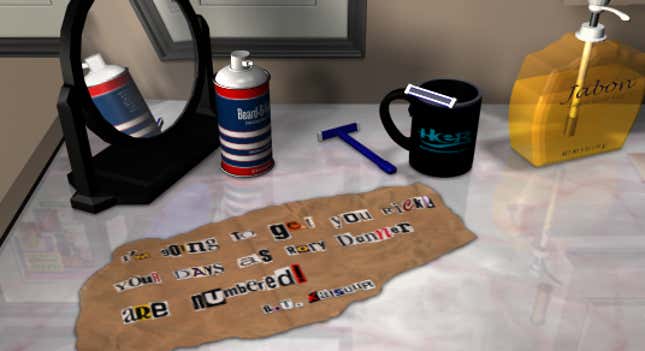

I’d been tearing through the library’s collection of Nancy Drew books, and I couldn’t get enough of the “titian-haired sleuth.” I wasn’t the only one. The first book to tell the story of the teenage detective, The Secret of the Old Clock, came out in 1930. Over the next 73 years, the 175 books in the core Nancy Drew series entranced generations of young women. My mother and grandmother had also grown up reading about clever, capable Nancy; her best friends, Bess and George; her boyfriend Ned; and Nancy’s hometown of River Heights, which was beset by more crimes than New York City in the 1980s. The PC game Stay Tuned for Danger, which my parents brought home around 2001, updated Nancy for the new millennium by placing her on the set of a soap opera, where the star was getting death threats.

My sister and I played Stay Tuned for Danger over and over. We were entranced by Nancy, who could solve any problem she encountered. Nancy was also a girl, and the other series we played (Mario, Pokémon, Spyro, and so on) were specifically, clearly, constantly about boys.

“[Nancy] broke the mold,” said Cathy Roiter, who designed Nancy Drew games at Her Interactive from 2008 until she left in 2016. “She was smart, she was independent, but that didn’t mean she didn’t rely on her friends and family. She was able to do whatever she put her mind to.”

My sister and I weren’t the only ones who loved seeing girls like us star in an adventure. Most of our friends had Nancy Drew games, too. For years, we swapped the boxes we’d bought from the Target or Best Buy shelves with our allowance money.

Even girls who didn’t identify as gamers knew this incarnation of Nancy. My roommate Josephine told me that she’d never really played video games. But as I was writing this article, she recognized the voice from the YouTube game footage clips I was watching. “That’s Nancy Drew!” she said. I asked her, surprised, how she recognized Nancy’s calm, clear voice acting.

“I played the games when I was little,” Josephine said. “I’d forgotten until now. The games just seemed like good stories, you know?”

Good stories for young women were Her Interactive’s goal from the beginning. In 1995, laserdisc arcade game developer American Laser Games created Her Interactive as a subdivision that would target an untapped market for video games: girls. In 1995, the biggest effort to make games for girls had been Mattel’s Barbie titles, which were almost all fashion and makeup-based.

Her Interactive’s first game, McKenzie & Co., was about a group of high schoolers trying to find a date to prom. Although McKenzie & Co. feinted at empowering girls (“McKenzie” turns out to be an acronym in which the second “e” literally stands for “empowered”), it also focused on the same traditionally feminine activities, like fashion and romance, that showed up in the Barbie games.

But McKenzie & Co. did well enough for Her Interactive to take a risk and pivot to more cerebral mystery games. The company changed its slogan to “For Girls Who Aren’t Afraid of a Mouse” and released the first Nancy Drew PC title, Secrets Can Kill, in 1998. Secrets Can Kill was a point-and-click mystery adventure with graphics that suggested three-dimensionality, which, in 1998, was impressive enough to net the game an audience. Soon, Her Interactive released another Nancy Drew mystery, and then another, and another. In 1999, it absorbed its parent company, American Laser Games. By 2000 the series was popular enough to warrant write-ups in the New York Times, where writer Charles Herold dubbed Her Interactive’s vision of Nancy “the un-Barbie.”

Between 1998 and 2015, Her Interactive published thirty-two flagship Nancy Drew games for the PC, as well as a handful of games for other platforms. The company’s incredible output was the result of a production schedule that pushed out two new games each year. Like clockwork, the studio would release one game in the summer and the other right before the holiday season.

“The fact that we could knock these games out every six months still blows my mind,” said one former employee. “We had a schedule, and once you get the deadlines understood… It’s incredible what we were able to produce.”

Despite the demanding schedule, Her Interactive never grew beyond a single office. The company averaged thirty to thirty-five employees in the 2000s, though that number sometimes swelled to fifty when Her Interactive tried new ideas that required contract work. Her Interactive used contractors infrequently, which was yet another unusual practice in an industry that often keeps workers for the length of a single project.

Instead, the company kept all its art and design in-house, according to former employees. Employees racked up year after year at Her Interactive’s Bellevue office, and everyone I talked to emphasized how much that office felt like a second home. “It was a great culture. We got along and enjoyed what we did,” said Roiter.

“Her Interactive was not the most competitive salary out there in the video game industry, especially with Microsoft and Amazon [nearby]. But there were a lot of different benefits that you don’t find in bigger studios,” said a former employee.

Fans developed the same kind of attachment to the Nancy Drew games. When each new mystery came out, hardcore fans would rush to big-box stores so that they could complete their jewel case collection. The fans, who dubbed themselves the Clue Crew, investigated every corner of every game, mailed fan art to Her Interactive’s office, and volleyed posts back and forth for hours on Her Interactive’s online forums.

Outside of Her Interactive, the game industry was changing dramatically. But from 1999 until 2015, Her Interactive’s formula stayed the same: Nancy as unseen player character, voiced by the same actress, inhabiting aesthetically similar worlds, solving two mysteries a year, never aging.

For a long time, it seemed like Her Interactive was somehow immune to the risks that had tanked so many other video game studios. Then things changed.

Stuart Moulder knew it was going to be a challenge to turn Her Interactive’s finances around when he assumed the position of CEO in May of 2011. “They were running at a loss,” Moulder said of the company. “They weren’t quite covering their costs.”

The game studio had been in the red for some time before he arrived to take the place of Megan Gaiser, who had been CEO for the previous 12 years. Gaiser had established Her Interactive’s reputation and production schedule, but even she hadn’t been able to successfully adapt the Nancy Drew games to the next big platform: mobile. (Gaiser declined to comment for this story.)

In 2011, the year the first iPad came out, games like Infinity Blade II, Tiny Wings, and Tiny Tower were captivating iPhone and Android gamers. These games were action-packed and easy to put down and pick up again. The Nancy Drew games, which required intense focus and could only be played on the PC, were the opposite.

Her Interactive had occasionally tried making games for other platforms, like the Game Boy Advance (Message in a Haunted Mansion), the DVD player (Curse of Blackmoor Manor), and the Wii (The White Wolf of Icicle Creek). None had been financially or critically successful. A few months before Moulder arrived, Her Interactive had released a mobile port of an earlier game, Shadow Ranch, that had been adapted into a more casual, hidden-object-style title. But the Shadow Ranch port went in the wrong direction. It wasn’t interactive or exciting enough. “Shadow Ranch didn’t achieve much in sales,” said Moulder, “and it didn’t make back its costs.”

Moulder, who had gotten his start as a manager at Microsoft, was an experienced businessman in the software field. From 2011 to 2014, he said he tried to pick up more investors for Her Interactive, as well as create a successful mobile Nancy Drew game.

The bulk of Her Interactive’s funding had always come from a venture capitalist who helped found some immensely profitable biotech companies. The venture capitalist supported Her Interactive not because he thought the company would net him another billion, according to Moulder, but because he thought that making logic puzzle games for girls was the right thing to do. “If you think of games as food, we were definitely more in the vegetable category than the sinful dessert category,” said Moulder.

But if Her Interactive was going to make a mobile game work, it needed a bigger marketing budget—and that meant more investors. Moulder pitched the company to investor after investor, but nobody bit. There were two reasons for that, he thought. First, Her Interactive had been around for over a decade. It wasn’t a scrappy startup filled with college dropouts, but rather a known quantity.

Second, Her Interactive didn’t own the Nancy Drew intellectual property. Book publisher Simon and Schuster did, and not only did Her Interactive have to pay Simon & Schuster royalties for each game, but the publisher wasn’t actively promoting the Nancy Drew series. Her Interactive had to generate its own publicity.

“Yes, we do have other investors,” said Her Interactive’s Jared Nieuwenhuis, when I asked whether the investment situation had changed since Moulder’s time. “That’s private information. We’re a private company.”

One day in mid-2014, according to three former Her Interactive employees, Moulder didn’t show up at the office. People started to worry, and even panic, as they realized he wasn’t at work. Was he sick? Had something horrible happened?

It would take over a week for the rest of the office would learn that their CEO had abruptly decided to quit. “His departure was very sudden and unexpected. It was not a thing that we knew about, or had any hint of,” said one former employee.

Stuart Moulder does not mince words or shy away from past snafus. When I asked him about his departure, he paused only briefly before saying, “What I tried to do hadn’t been successful.” It was emotional, he said, to leave knowing he hadn’t done what he’d come to Her Interactive to do. “I didn’t handle my departure well. I was embarrassed. It was just-” He sighed. “Ugh.”

Outside the Her Interactive offices, everything seemed normal. The Clue Crew didn’t know about the odd circumstances of Moulder’s departure. Another game, Labyrinth of Lies, came out in October of 2014, just as expected.

Even the staff wasn’t that shaken by Moulder’s disappearance. “Once Stuart left, we were all a little weirded out, but nobody took that as a sign to get out of there,” said a former employee. “We really wanted to finish our next project.”

For the next month, as the Her Interactive board searched for a new CEO, the developers kept working with no CEO at all. “We were such a self-reliant studio that we just kept plugging,” said one person.

Then a new CEO came on board, and the fans started to get mad.

Penny Milliken had been a former Disney marketing director, as well as a member of Her Interactive’s board, before she took Moulder’s place in 2014. She had plenty of experience, but not in the games industry.

Shortly after Milliken began her tenure, in November of 2014, the company made a decision that incensed fans: It let Lani Minella go. Minella had voiced the character of Nancy Drew since the very first game, but her last would be Sea of Darkness, which came out in the spring of 2015. For the next game, Midnight in Salem, Her Interactive planned to find a Seattle-area actress who sounded younger. The decision may have made sense financially, but it angered the Clue Crew and disappointed Minella. “I never realized what a fan base I had until I started going on some of the forums and seeing some of the reactions to me being let go,” Minella told me.

“No one can replace the character you gave Nancy for all these years. They’re making a mistake,” wrote one Twitter user in response to Minella’s announcement. Petitions popped up on Her Interactive’s forums asking the company to rehire Minella.

“I thank [Minella] profusely for her many years of service to the company and being the voice of Nancy Drew,” said Her Interactive’s Nieuwenhuis, who would not elaborate on why the company cut ties with Minella. “But that’s in the past, and we’re looking forward. Lani is a tremendous talent, one of the best voices in the industry. We wish her the best going forward.”

Meanwhile, Milliken was figuring out what it would take to switch the Her Interactive team to another game engine. A game engine is a code framework that can be used from game to game in order to expedite the development process, and the Nancy Drew games had always been made on a proprietary engine, one that was developed by Her Interactive itself. By 2015, this engine had not received many modern updates and felt clunky to use, according to people who worked on it. Milliken began looking into the popular game engine Unity.

“It was a nice pipe dream that everyone could learn to use Unity in a month and then we’d all ride off into the sunset and make games for mobile and PC in Unity… but how was that actually going to happen? And nobody really had a good answer because nobody had the expertise,” said one former staffer.

When asked about this transition—and Milliken’s lack of expertise in game development—Her Interactive’s Nieuwenhuis defended his company’s boss. “Penny is the CEO,” he said. “She’s not writing code for us. Penny sets the direction and strategy for the company, and she does a great job of that. Thinking that you need a CEO who understands every nuance of Unity is just incorrect. Penny has a long and illustrious career in the entertainment industry with stops at Disney, amongst others. She’s got an incredible track record of success. To think that she needs to understand every facet of the game development process is, I think, flawed. Like any good leader, she sets the strategy and then lets people who understand the program well, understand game development well, go forward.”

While both those conflicts steered Her Interactive off-course, a different issue threatened the company’s finances: where to sell the games. Her Interactive had always made money selling physical copies in big-box stores like Target or Best Buy, where parents shopping with their kids could pick up the latest mystery game. As online platforms like Steam and GOG started to explode in the late 2000s and early 2010s, in-store sales of PC games plummeted. Across the video game industry, physical sales decreased from 80% in 2008 to 31% in 2015.

Her Interactive didn’t want to sell its new releases on Steam, however. While the company added part of its back catalog to the digital gaming giant, it waited years to make other titles available. (Sea of Darkness came out in 2015, for example, but wasn’t available on Steam until February 2017.) Upper management felt that Steam took too large of a percentage for new sales on the platform to be profitable, according to two former employees, so Her Interactive relied on its own online store. But this store was plagued with problems and bad design decisions. Games disappeared from owners’ digital libraries without warning, and the store would force players to buy an “extended download” add-on for $6 if they wanted to download a game more than once. This was a problem before Milliken took over, and it wasn’t until recent years, under Milliken, that Her Interactive shifted course.

“We have our entire library available on Steam now,” said Nieuwenhuis. “As far as I’ve been here, it’s always been a priority to get our games on Steam as quickly as possible.”

In late March 2015, the layoffs happened. At least two other employees ended up quitting in the following months, bringing the company’s headcount down even further. Cathy Roiter, the lead designer, had kept her job through the layoffs but ultimately quit in 2016, frustrated by the lack of development progress. “I was looking to be part of a team that was actually creating products again,” she said.

In August 2015, Her Interactive publicly announced its plans to move to the Unity engine and said that the next Nancy Drew game, Midnight in Salem, would be out the following year. Baffled fans reached out to Her Interactive to figure out how such a small studio, especially one that had lost many of its creative staff, was going to finish the game. Suddenly, the company’s communication started getting weird. Though Her Interactive kept tweeting, posting on Facebook, and publishing blog posts nearly every day, mentions of Midnight in Salem disappeared unless fans asked outright. Threads criticizing the communication shift somehow vanished from the Her Interactive forums, according to irritated fans. Some fans suspected that they had been banned for asking questions about the game.

When asked about this, Nieuwenhuis said that the speculation was incorrect. “We don’t do that at all, and this is something I directly manage,” he said. “We have a very liberal social media policy, and we’re fine with criticism. The only time we ban people is when they use certain language or make personal attacks against employees. Things of that nature we will not put up with, and then we would ban them, or ban them for a short period of time.”

In October 2016, some particularly dedicated fans created a megathread containing every response from Little Jackalope, Her Interactive’s community manager, relating to Midnight in Salem. The responses all sound similar: “We can’t confirm an exact launch date,” “I can’t give a specific launch date on Nancy Drew: Midnight in Salem,” “[Midnight in Salem] is not declared “shelved,” we just don’t have any new updates to share about it.”

The last straw for the fandom had come a little earlier that year, when Her Interactive released a mobile app for kids called Codes and Clues. Not only was Codes and Clues for a different audience (it re-imagined Nancy as an elementary school student searching for a missing science fair project), but it was an educational game that taught basic programming skills, not a story-focused mystery. Since Her Interactive had laid off its creative team, Codes and Clues was developed by F84, a mobile app development studio in California.

“I’m being petty and I refuse to play it because I’m pissed about Midnight in Salem :)” wrote one fan on the Nancy Drew subreddit, which has around 6,000 subscribers.

Despite fans’ anger, and despite the silence from Her Interactive, the Clue Crew hangs on. They’re still hoping that the long-awaited Midnight in Salem is just an announcement away from becoming reality.

The question remains: will it?

For a studio that has been so secretive for the past few years, Her Interactive has set Midnight in Salem expectations high. In the company’s October 2016 letter to fans, the studio said that it had made “significant progress” on the game’s art and programming assets. In a December 2017 letter, Her Interactive teased the possibility of an AR/VR title.

The idea of another Nancy Drew video game—produced internally by Her Interactive, at least—seems improbable. After years of delays, Her Interactive said in that December 2017 letter that it was targeting a release of spring 2019. If Midnight in Salem does come out then, it will have been four years since the 2015 layoffs and three-and-a-half years since the originally announced release date.

I can’t say for sure what Her Interactive is doing, since the company wouldn’t give me any precise information. When I spoke to Nieuwenhuis, I asked if Her Interactive had any creative staff at this point, as I had only been able to verify a handful of people as current employees. He said yes, but would not say how many people they’d hired since the 2015 layoffs. Nieuwenhuis said those new hires were working on Midnight in Salem in Her Interactive’s Bellevue office, but wouldn’t say what parts of the game they were tackling. He said that Her Interactive was outsourcing parts of the game’s development, but wouldn’t say what, or to whom. He said that Midnight in Salem will indeed have an AR/VR component, but wouldn’t estimate when he’d be able to share more information about it.

“I hope you can understand my position in questioning whether the game is going to come out in spring of 2019. Without concrete information about who’s making the game, it’s a little hard to know what to say,” I told Nieuwenhuis.

“Okay,” he said. When asked for other reasons the game had been delayed, he added: “We took a real holistic, 360-degree view of the entire franchise as well. When we decided to move away from our proprietary engine and look to Unity as the platform we want to build on going forward, that was the perfect time to re-examine everything we’d done in the past and really take a look at what we’ve done best, what we want to do better, what we want to improve. This is more than just jumping to a new game engine. It’s bigger than that. Sometimes that gets lost in the message when all our fans want to know is when it’s coming out. But it’s much bigger.”

Former Her Interactive employees said they were skeptical of the game’s progress. “I don’t think Her Interactive is salvageable at this point,” said one. “I really just want the story to be told so that fans have some closure. It’s like a missing child case. They’re waiting for little Billy to come home. And I’m like, ‘I’m sorry, but Midnight in Salem is never, ever going to come out.’”

Whether or not we see Midnight in Salem, the long hiatus of Her Interactive has been a major loss for the world of video games, which, in 2018, needs a heroine like Nancy Drew more than ever. According to Feminist Frequency’s yearly E3 breakdown of protagonist gender, only 8% of games previewed at E3 2018 featured a protagonist who was specifically designed as a woman. (50% of games allowed the player to choose between male or female protagonists.) This is not an improvement from the past few years.

Nancy Drew is an imperfect feminist character—she’s straight, white, and eternally good-looking—but her status as a pop culture icon is indisputable. She never wavers, never gives up, never allows fear or intimidation to get the best of her. She solves the case, over and over again.

“I still believe that Nancy Drew is timeless,” said Cathy Roiter when I asked her if Nancy Drew had a place in the current games landscape. “There is always a place for women in gaming.”

These days, Her Interactive is like an old mansion that Nancy might investigate. It’s a home that used to hold grand parties in the ballroom and spirited debates on the veranda, but the doors have been shut and locked for years now. Someone still lives inside, but nobody knows what they’re doing, or why they’re still there. Maybe one day soon they’ll emerge carrying something beautiful, the product of years of work. But they’ve been gone for far too long.

Elizabeth Ballou is a writer and MFA candidate in game design at NYU’s Game Center. Her Gwent deck brings all the innkeeps to the yard.