It’s hard to overstate the importance of Sir Clive Sinclair’s role in the world of computing. His inventing the ZX Spectrum home computer in 1980 radically changed the masses’ perception of, and access to, computers. His work created the path to not only gaming, but also the creation of games, by regular people. He died yesterday at the age of 81.

Born in Surrey, England in 1940, Sinclair found success in the 1970s, inventing and developing electronic calculators, through his company Sinclair Radionics. He later formed Science Of Cambridge (later Sinclair Computers, then Sinclair Research), where in 1979 he set out to revolutionize home computing by making an affordable product to rival the expensive personal computers that existed at the time.

The Commodore PET cost £700 (or $795 in the US, equating to approximately $4,000 today). Sinclair’s ZX80 launched in 1980 at £79.95 ($182 by 1980 conversion rates) for a home kit, or £99.95 ($228) pre-built. It was so much cheaper that it became an instant success, allowing computers to become something available to ordinary people. But it was in 1981, with the release of the ZX81, that Sinclair became a true household name.

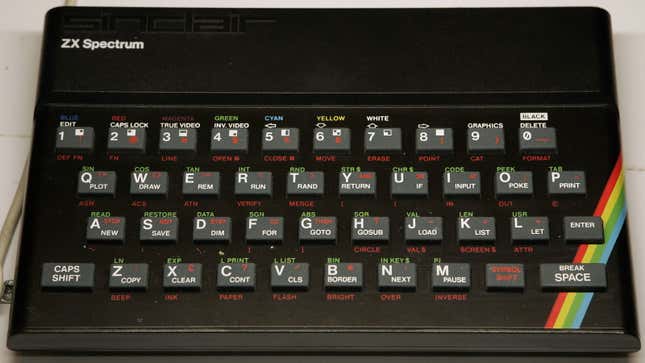

That machine cost an extraordinary £49.95 as a kit, and £69.95 pre-built, and went on to be the biggest selling home computer in both the UK and the US, along with Japanese sales via Mitsui. (US readers may well know it better by the rebranded Timex Sinclair name.) Then came the iconic ZX Spectrum, most popular in its 48K and 128K forms.

It’s impossible to overstate the impact this had on all of computing as we know it today, making home computers a normal, affordable product, giving families access to the tools needed to not just use software, but create their own. While the Atari gaming systems and their many mimics were popular in the late ‘70s, they were closed boxes, one-way streets. Via the BASIC programming language on the ZX machines, homebrew development boomed, leading to the formation of many of the most popular developers of the ‘80s.

Via the cottage industry of Spectrum development, you can draw a direct line to GTA. DMA Design was a group of amateur Spectrum developers meeting at a computing club, eventually creating Lemmings, then later Grand Theft Auto. They became Rockstar North, and you know the rest.

Or how about Rare? They began as Ultimate Play The Game, post-arcades primarily developing for the ZX Spectrum. Or Ocean Software, begun by Jon Woods and David Ward as Spectrum Games. They were mimicking the success of Bug-Byte and Imagine (who led to Psygnosis). Codemasters, who got started on the VIC-20, found their success working on the Spectrum. Or Infogrames... You get the idea.

Speaking personally, the ZX machines were such a pivotal part of my life. My father, a dentist (NHS, not private), bought the ZX81 on launch at enormous cost to our pretty broke household. He started figuring out BASIC, and began coding ideas for it, and got involved in the community that surrounded. This led to his somehow being sent a pre-release ZX Spectrum 48K to review (I wish I knew who for, but never asked before he died in 2016). He started writing for fanzines, while I (aged 4 in ‘81) started caring about reading so I could play the text adventures he was buying.

Dad went on to get a game published as a type-in in a magazine (Warlock, 1984, which I contend was the first rogue-lite, and you can play it here), and I went on to write some BASIC that made the borders of the screen flash while it printed the word “BOTTOMS” in an infinite scroll. But I also started writing about games, getting first printed in a fanzine called Adventure Probe, and now it’s now.

The Spectrum (or Speccy to its affectionate fans), was a huge part of British computing, a crucial step toward the Atari, Amiga, and then home PC. A magazine industry sprung up around it, leading to the greatest ever print magazine, Your Sinclair, that was the most important publication of my childhood. (I would sell my house for a “Your Sinclair: IT’S CRAP!” t-shirt.)

Far too many obituaries of Sir Clive are obsessing on his later failures, most especially his wonderfully ambitious ideas for electric vehicles, decades ahead of the rest of the world. Sneering at the C5 is a woeful distraction from the world-changing effect of the Speccy, and undermines his successful drive to make computing accessible to people, not just industry. The world of gaming in which we revel would be so woefully less without Sinclair.

Sinclair died at home in London, yesterday, having lived with cancer for more than ten years. He’s survived by his three children, five grandchildren and two great-grandchildren. RIP.