When I was a child, I excitedly anticipated the commute my mom and I took every Sunday to our humble Black Lutheran church in Cabrini Green. But what excited me wasn’t hearing the children’s sermons from our youth pastor or the potluck lunches that followed morning service. My excitement came from pulling out my Dragon Ball Z action figures, showing them off to my cousin Jordan, and if I could get away with it, playing with them during the service.

I adored Dragon Ball. I would book it toward the anime section of Blockbuster to habitually rent out its films and color inside the manga I twisted my mom’s arm to buy from the also very-out-of-business Borders. But of all the characters in the DBZ ensemble of otherworldly warriors, Piccolo, the series’ introverted villain-turned-Z-fighter, was who I felt the closest kinship to.

After scrounging up enough of my allowance to purchase a Piccolo keychain for my mom (I didn’t have a set of keys of my own at the time) from my school’s book fair, my mom asked why I got Piccolo instead of Goku or Vegeta, the heroes of the series.

“Because he’s Black,” I answered plainly.

If you were to ask any DBZ fan what race Piccolo is, they’d likely say he’s a Namekian, a green slug-like alien from the planet Namek. But when put in context, with him usually serving as the sole representation of an “other” (outside of Mr. Popo but I don’t have the energy to get into that) among a cast of white-presenting characters, Piccolo was my representation.

My ability to identify Black-coded characters like Piccolo became second nature as I matured in a world infused with cartoons and anime. Black-coded characters are not technically “Black,” typically because the race system we’ve constructed is not mirrored in the worlds they exist in. They are instead “coded” as Black in how their stories or representations often mirror the Black experience in America. Whether it be in the face of adversity from villains or allies alike, these characters stand by their convictions and make sure their voices are heard. Other examples include Naruto’s Rock Lee, Goliath from Gargoyles, and Knuckles from Sonic X.

This isn’t to say that there weren’t Black characters for me to identify with growing up, either. But they were few and far between, which is partially why coded characters, be they Black-coded, queer-coded, or otherwise, are popular among those who share that identity.

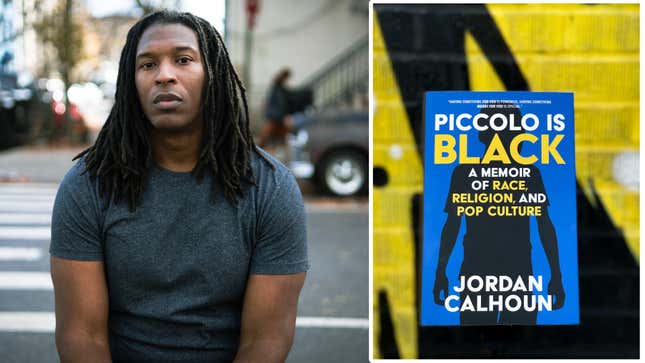

I wasn’t alone in this experience. Jordan Calhoun, the editor-in-chief of Lifehacker and The Takeout, recently published a memoir titled Piccolo Is Black: A Memoir of Race, Religion, and Pop Culture that explores this very idea.

I spoke with Calhoun about Black-coded characters and how their prevalence in popular media helped shape the person he is today.

This interview has been lightly edited for clarity and brevity.

What was your ‘ah-ha moment’ about Black-coded characters’ existence in media like anime and cartoons?

I think I knew it on an emotional level as a kid, but I didn’t understand it on an academic intellectual level until I was an adult. As a kid, me and all my friends thought it was pretty obvious characters like Piccolo or characters that had a Black voice actor just seemed intentionally Black. They had a story that mirrored what we recognized as the Black experience in the United States. But it wasn’t until becoming an adult that I was able to look at that within the context of the history of animation and a broader cultural picture where animation was really racist in the ‘50s and ‘60s. There was a transition period where Black audiences weren’t really considered as a marketable audience so we wouldn’t get much representation. We just got errant tokenism.

The ratio that I describe in the book is a one-to-five ratio. You would have a group like the Power Rangers, and there would be one Black person and sometimes there would be one Asian person and the rest would be white. That was largely because there was a transition happening where Black people were seen as like, ‘Let’s throw them a bone, let’s have some diversity, let’s have some representation. But let’s not focus too much on them because then we won’t be able to sell these toys. We won’t be able to sell these comics. We won’t be able to sell this merchandise.’

You mention in the preface that Piccolo Is Black wasn’t initially written as a memoir. What made you change your mind?

I didn’t want it to be a memoir. I wanted it to be an approach to all of these same themes and topics, but from a more distant, safe academic context. It would be talking about the history of animation, racial coding, [and] the mental adaptations that Black kids made in the ‘80s and ‘90s during the transition of animation from being super racist to less racist. But my publisher and a few editors who read the early manuscript of the book told me that readers are going to care most about how it affected me as a person.

How did you decide what to share and what not to share?

The decision that I made was that honesty would be my North Star. Whatever experience I felt, whether I was excited or ashamed of it, whether I look good or bad, or whether other people in my life look good or bad I decided I’m just gonna write things as they happened.

The funniest example is that the entire first draft of the book did not include my dad. [laughs] I just didn’t mention him at all. And it wasn’t that I was intentionally trying to write my dad out of it. It was that I just didn’t didn’t think about it. It ended up being probably the first heavy story in the book. It wasn’t until an editor pointed out that a reader’s gonna wonder where your dad is. ‘You have to either write him outta the book intentionally and explain that he wasn’t in the picture, or you have to explain something of his involvement in your life.’ Is this a comfortable story to tell? Absolutely not. Is this a story that I wanna tell? Nope, but this was definitely formative in my life and helped move my life in certain directions.

One of the things that offered me a little bit of comfort in writing the challenging things is that I wrote the entire book from the perspective of whatever age I was at the time. The reader can say, “This is happening to a kid? Oh, that’s perfectly fine.” Or “This happening to a kid is absolutely not okay.” I’ll just say the things that it made me think, feel, or do, and readers can decide whether that’s appropriate for adults to have taught that to a kid and if that was a normal response for me as a kid.

How were Black-coded characters like Piccolo from Dragon Ball Z, Goliath from Gargoyles, and Optimus Prime from Transformers significant to you as a child and as the writer you are today?

They taught me a degree of confidence. Being confident in a place where you are not well represented, being confident in a place where you are outnumbered and you are sticking to your own morals, ethics or opinion. Not to say that you’re close-minded about things. One of my favorite things about Azeem from Robin Hood: Prince of Thieves, Goliath, or Dinobot from Transformers: Beast Wars was that, in the face of a dominant culture, they did not give a shit. They had a strong sense of who they were and they were gonna be unwavering in what they knew they were right about. That was the trait that I wanted to adopt. I wanted to say, “This is what I think is right,” or, “This is who I am,” without trying to bend to the majority.

The thing that sticks with me even to this day is that, if I’m in an editorial meeting, I am one of two or three people of color in that room. And I’m still gonna use my voice. I’m still going to stand by what I think is right and not be intimidated, even though there’s a ratio worse than one-to-five. Your point of view can be not well-represented in a room by volume, but you could still have a voice in that room. That was always my favorite thing as a kid: watching characters who had a strong sense of self in the face of a dominant culture that wanted them to change or be silent.

What are the biggest changes you’ve seen in pop culture when it comes to its depictions of Black-coded characters?

My childhood experience obviously resonates with me because it was what I had, but that’s not ideal. The thing that I would want for today and for the future is for us to not need to be coded as Black to be palatable for white people or for them to be able to connect with our experiences and to see us as meaningful characters.

The racial coding was a segue into a better future. It was a segue in the way that Black people weren’t seen as a viable audience that would actually buy things or carry a TV show or a movie. It wasn’t until very recently in Black Panther that it was proven with an exclamation point that a predominantly Black cast could sell very, very well.

When I think about the connections I made when I was a kid, I look at it in both good and bad ways. On the one hand, it’s really shitty that it was necessary for me to learn racial coding because I had such poor representation of people who look like me. On the other hand, the thing that I celebrate and shine a light on in the book is that we did it. We were able to adapt to that underrepresentation. We found ways to see ourselves as powerful characters.

What advice do you have for other Black nerds who felt or still feel seen through Black-coded characters that you wish you’d gotten as a kid?

Embrace the fandom. The opportunities to embrace the fandom and to find like-minded people are far broader today than they were when I was a kid, obviously, thanks to the internet. When I was a kid, being a nerd was about knowing something that’s niche, something that popular culture does not accept as cool. The definition now of being a nerd, for me, is having things that you love enough to want to share with other people. If you have something that you love, whatever it is, that you’re sharing with other people and you’re being inclusive, that is beautiful. That’s the nerd future that I want.