For the first two hours I spent with it, Photographs came close to being one of my favorite puzzle games of the year. It was everything I could want: Aesthetically beguiling, with a surprising story and puzzles that offered the perfect amount of challenge. Then the story took a turn that was so fucked up that it soured me on the entire game in seconds.

Photographs is a collection of five short stories to be played through in order, each with their own kind of puzzle game elegantly themed to match the corresponding narrative. “The Alchemist” tells a story about a man who lives alone with his daughter in the woods, selling cures out of his home. You guide figures representing the Alchemist and his daughter through a garden that becomes more dangerous as the little girl falls ill. In “The Preventer,” a young woman at a school for wizards who toys with time to prevent disaster falls in love, and in her story you play match-3 puzzles as she learns the work—and danger—of using magic to save people.

Another story, “The Journalist,” tells a generational tale of a man who started a newspaper, and his grandson’s efforts to keep it afloat. For this story, the puzzles are all mazes that require the player to trace a path from one point to another. As the story progresses, the puzzles get harder as more hazards get introduced, like erasers that follow preset routes and will erase the line you’re drawing, forcing you to go back.

Details big and small give these puzzles character. To continue using “The Journalist” as an example, the mazes are all styled to look like the front page of a newspaper, and the line you are drawing is traced by an on-screen ballpoint pen. As you move your line through the maze, the date on the front page ticks up rapidly, conveying the passage of time.

The visual economy and spare storytelling at work in Photographs is tremendous, and extends through the narrative parts of its short stories, which are conveyed in first-person narration by their protagonists while an ever-changing diorama appears on-screen. So, in our example level, you see the modest newspaper building as desks are added, floors are rented out, and technology changes with the times.

Paying attention to the diorama is also how you advance the story: In the narrative portions of Photographs, you have a camera that you peer through by touching or clicking on the screen; across the bottom of the viewfinder you’ll see a clue indicating where you should focus in order to snap a photo and continue the story with another puzzle.

When all of this comes together, Photographs feels really special—like in its first story, about a man’s desperate struggle to save his daughter from an unknown illness. There’s so much to appreciate: the lovely art, the tender score, the clever twists in the puzzles, which involve navigating a garden with increasingly complex hazards. It all feels considered, like there isn’t a single extraneous pixel.

Were it not for what happened at the end of “The Journalist,” I would have recommended Photographs to anyone expecting something unusual and sad with an aesthetic largely used for what you might call “indie game whimsy.” But in its final two hours, Photographs became something else entirely to me—misguided in its ambition, and perhaps even reckless. It wanted to tell me a tragedy, but I doubt the one I walked away with was what it intended. It’s a shame that the stories Photographs tells take such an alarming left turn that’s hard to get past.

“The Journalist” is a straightforward enough tale at first, but this is a game about details, and the details in this story might make you raise an eyebrow. The grandfather names his paper The Uplift and the narrator, his grandson, talks about the paper’s mission to tell “good news”. Since “The Journalist” is the fourth of the game’s five stories, at this point in the game you’ll have a solid grasp of the game’s dramatic leanings, and guess where it’s going.

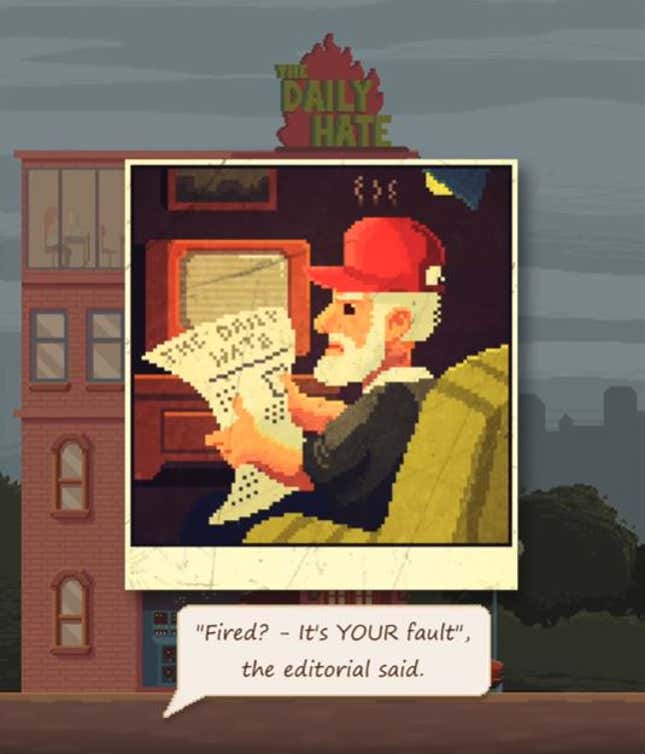

As the years go by, readers start to lose interest in The Uplift, and instead are drawn to a new paper, The Daily Hate, which shamelessly chases readers with mean-spirited bad news and vapid gossip. The Daily Hate is so successful that The Uplift cannot compete, and the journalist has to fire some employees. Later, “tired of firing people,” he sells Uplift to Daily Hate. “I wasn’t thinking about the effect we were having on the world,” he says. Later, we see a picture of one of the fired employees, a man wearing a prominent red baseball cap, reading Daily Hate and getting angry. Shortly afterwards, the man visits The Uplift’s office, which now belongs to The Daily Hate, and sets off two bombs inside it.

The static diorama immediately before this moment suggests the office is nearly empty, although the narration is dire. From what we can see, there’s a woman on the very top floor working. Below that, the protagonist seems to be alone with the bomber, after retreating to contemplate his regrets. “I made the world a worse place,” he laments as the bomber comes up to confront him after placing the explosives one floor down. “I doomed all my employees,” he says, just before the bombs go off.

This is all, Photographs unambiguously argues, the journalist’s fault for selling his paper to The Daily Hate, and the Daily Hate’s fault for publishing mean news.

You might think that this is nitpicking at a story that offends me because I am a journalist and predisposed to finding this kind of story offensive. The problem, however, isn’t just with “The Journalist” but the way its ending brings the central worldview of all of its stories into sharper focus. The chief lament of all the characters in Photographs seems to be “if only.” If only they had been more careful, or not looked somewhere they shouldn’t have been looking, or paid more attention to the impact they were having on the world around them.

On their face, stories that advocate for empathy and personal responsibility—even stories that use uncomfortable and arresting means to do so—are a good thing. But they’re only as good as the context they’re placed in, and the narrow scope of Photographs makes its arguments seem less like a call for empathy nestled in a tale of regret, and more like cloying admonishment, creating a victim willing to accept blame for the crimes of their killer.