In the late 19th century, Nintendo got its start making another type of game: playing cards. The company continues to make cards, and whether it’s the ones from past or today, the decks show off the beauty of Japan.

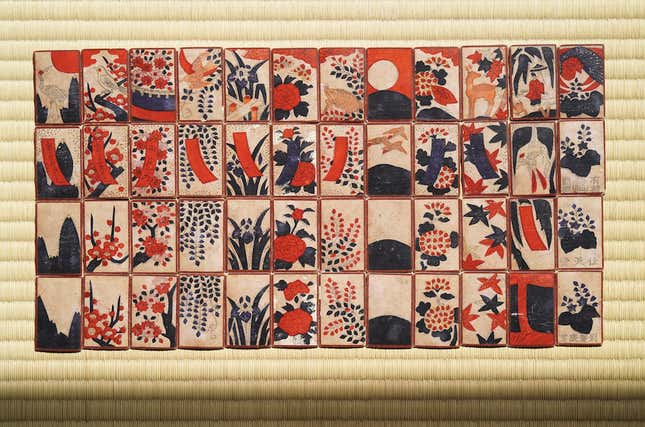

Hanafuda is a floral-covered card game that represents the flower and foliage of different seasons. For example, the 12 suits include plum blossoms, cherry blossoms, peonies, chrysanthemums and maple leaves, among others, with each reflecting seasons throughout the year.

Nature is one of the most important motifs in Japanese art, kimono textiles and tattooing. Considering how flowers are emblazoned on Japanese money, it only makes sense for one of the country’s most famous card games to be covered in the nation’s natural beauty.

“I bought this particular deck at an online auction a couple of years ago for a ridiculously low amount,” Osaka-based hanafuda collector and expert Marcus Richert told Kotaku. “I’m not sure if I even paid 1,000 yen (under $10) for it.”

Japan has no shortage of hanafuda collectors, and old, hand-made Nintendo decks like this are rare. Still, Richert says the few times he’s come across such cards, he’s been fortunate enough to snap them up at bargain-basement prices. Richert doesn’t know the exact date for the deck, but believes it could have been made between 1900 and 1930.

What makes this set of Nintendo cards extra special is that this deck was hand-printed. The technique, called kappa-zuri, uses a round brush through stencilling. The black outlines, Richert adds, were most likely woodblock-printed or done with a copper plate.

The practice of hand-stenciling cards, which had also been common in Europe, started to died out in Japan by the mid-1940s as the last artisans retired. Nintendo continued to use hand-made steps in the production of its hanafuda cards through the early 1970s, says Richert, even as they were machine printed. “The last step of pasting the backing paper onto the cards was really hard to automate.”

Hanafuda is now played at home during the Japanese New Year holidays, but over a century ago the game was a mainstay at illicit gambling dens. As Rebecca Salter notes in Japanese art magazine Andon, “The relationship between cards and gambling and official attempts at suppression, if not prohibition, is a theme that runs through the story of cards in Japan.”

The cards became so closely associated with betting, that gamblers would touch their noses to locate a deck or a den, because the Japanese word for flower (花 or hana) is a homophone for nose (鼻 or hana), perhaps explaining why the long-nosed yokai Tengu is found on hanafuda decks.

Today, Nintendo continues to make hanafuda cards, even giving them a decidedly Mario spin. But Nintendo isn’t the only hanafuda maker in the country—it’s not even the sole one in Kyoto. Oishi Tengudo, which was founded in 1800, still makes its hanafuda the old way: by hand. And while Oishi Tengudo never made the leap into video games, it’s perhaps Nintendo’s oldest rival, crafting beautiful cards of its own.

Richert has teamed up with Oishi Tengudo for a set of beautiful, hand-made hanafuda cards called Shiki. You can learn more about it on the project’s Kickstarter.