Manga pirates have operated in the internet’s shadows for decades, hiding from furious publishers whose translation efforts, pirates say, are shoddy, too slow or nonexistent. Now, as more pirates realize the potential value of their translation skills, they’re poking their heads out from the underground and asking for legit work. But the financial impact of the piracy industry they call home is pushing them back down into obscurity.

NJT is a reformed pirate. In 2006, he founded the manga piracy hub MangaHelpers.com, and four years later, the site welcomed 6.5 million visitors a month. For years in its forums, teams of Japanese translators would unlawfully scan, translate and disseminate manga to English-speaking audiences who could read that manga right on the site—and everything, including the labor, was free. Back in the mid-2000s, the aisles of Borders books were cluttered with teenaged bodies devouring manga like Dragon Ball or Fruits Basket, but American bookstores mostly sold the mainstream stuff. To get the lesser-known goods in English at a low price point, fans had to go to free sites like MangaHelpers or know someone in Japan.

“It was one of the most-accessed manga sites on the internet,” NJT told me over Skype this week. “We had the whole platform—translating, scan[ning], all in one community. If we were to go legit, we’d have a powerhouse to work with publishers for the greater good.”

Why do scanlators do it? First of all, only about 100 manga are simultaneously published in English. And according to three scanlators interviewed, they’re voracious manga consumers. Most asserted that they only work on projects without official or up-to-date translations. Kewl0210, who has scanlated Gintama, Jojo’s Bizarre Adventure and March Comes In Like A Lion said, “My general goal is to allow things that likely wouldn’t be readable to English speakers otherwise to have the opportunity to read them. Though there are some exceptions for me if I’ve done a huge amount of the series already and it gets licensed later and I just want to finish it.” He added that “There are also situations where the official translations are just bad.”

Over Skype, NJT vehemently insisted that scanlators’ work should be paid. He wants the illegal manga translation industry, which he’s helped spearhead for a decade, to end. And right now, he’s knocking on publishers’ doors asking to let him help them end it. Publishers are hesitating to play ball, though. “I’ve spent the last three years working [with publishers] to get that happening and I haven’t received a cent,” he said. “If they want to fight against pirates, they have to beat them at their own game.”

All scanlators interviewed said that working for an official manga publishing house in an official translator capacity is a far-off dream—no one had considered it in their younger years. Making a living translating manga never seemed like a real, attainable job.

“I might try to do it at some point,” Kewl0210 said. “Right now, I have a full-time job outside of scanlating and don’t really have time to do something like that, too.”

The manga translation industry’s history is entangled with its pirates’. Just as the Japanese comics were slowly making their way overseas in the early 90s, diehard manga fans were simultaneously “scanlating” them. The term refers to the illegal, underground practice of scanning Japanese manga, translating it, erasing the speech bubbles and replacing them with a translation. Back then, pioneering scanlators believed their favorite manga would never get official translations—or were angry at official translations’ poor quality or awkward localizations. (For example, lots of early translations replaced “ramen” with “spaghetti” or removed honorifics entirely, steamrolling the Japan-ness integral to several storylines.) So, in Internet Relay Chats (IRCs) and AOL Instant Messenger chat rooms, pirates constructed digital scanlation factories, impressively complex for work that went unpaid.

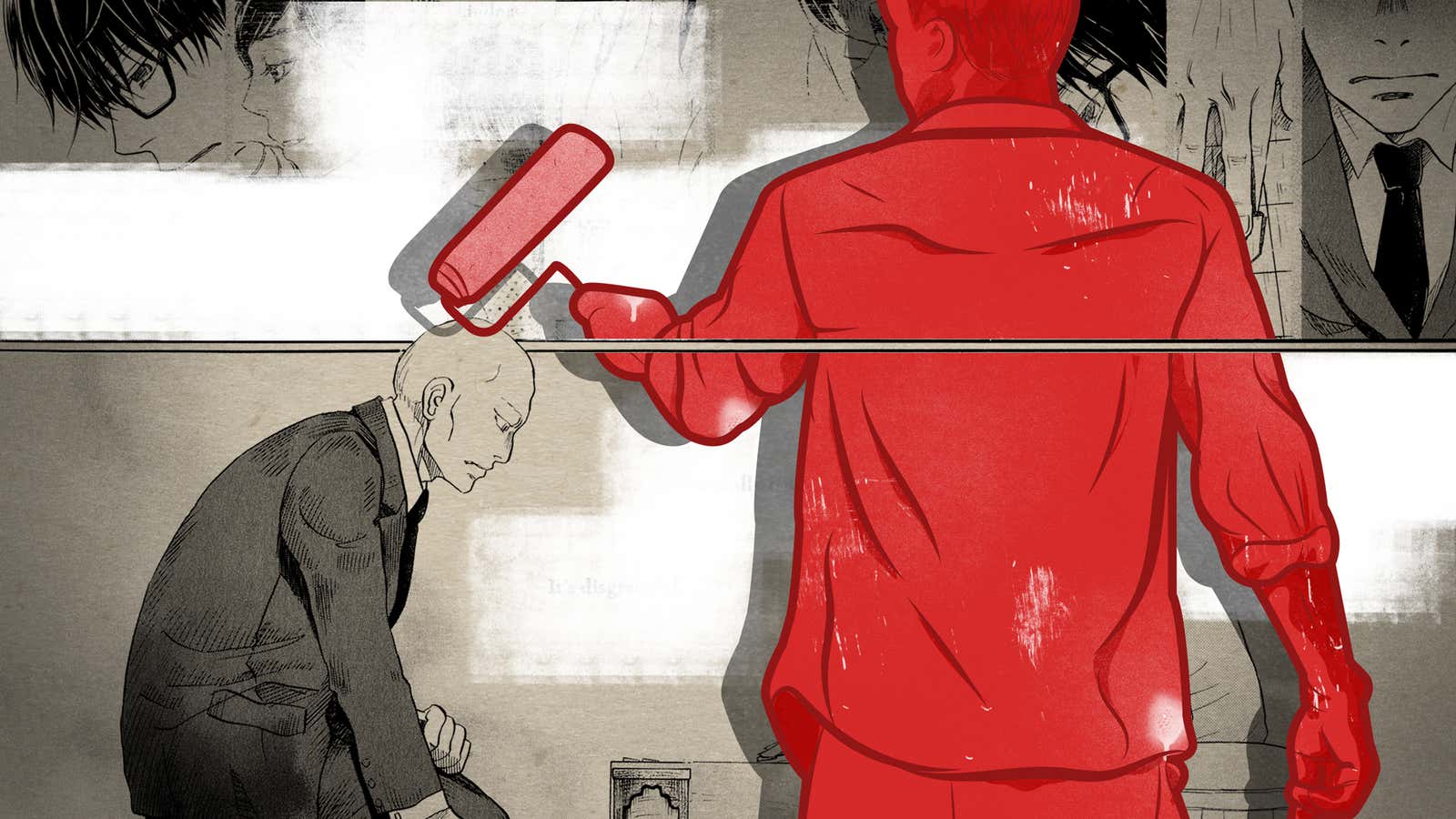

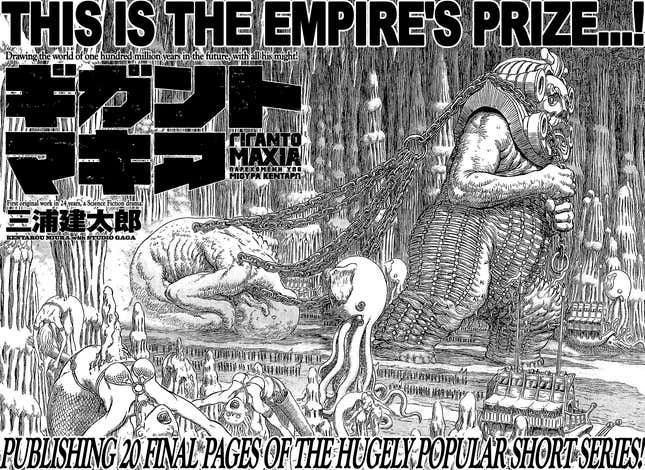

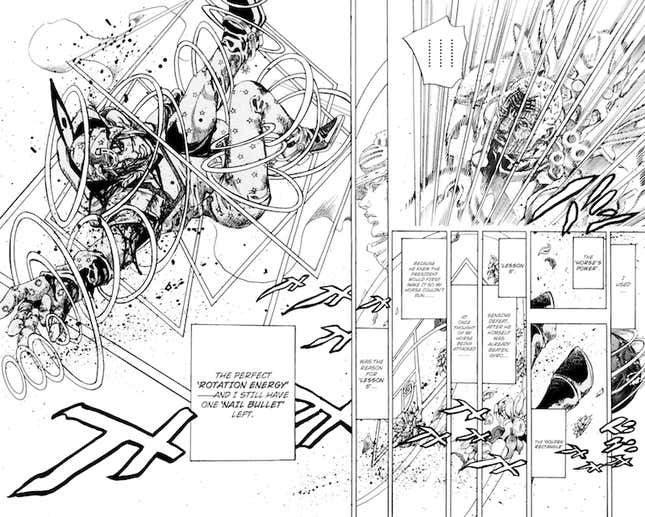

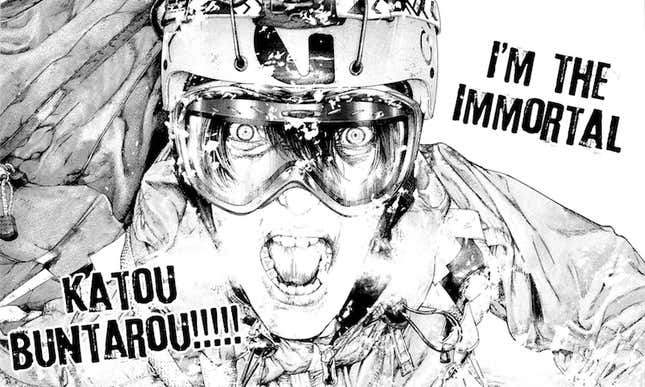

Now-quaint websites like AngelFire and GeoCities hosted those scanlations at first, mostly of classics like Ranma ½, Naruto, Love Hina or Dragon Ball. A lot of the time, these scanlations were rough. Several translations were amataur and efforts to redraw speech bubbles could be shoddy. In the early 2000s, “re-drawers” started filling in the space where a manga book was bound and scanned in the original artist’s style. Manga scanlators like Berserk’s would complete severed limbs or blanked-out background scenery with stunning faithfulness:

Manga’s American market value peaked in 2007 at around $200 million a year. That’s when, according to scanlation historian Gum, scanlation efforts increased twofold. Shortly after, the manga market crashed. In 2011, manga volumes published in North America plummeted from 1,500 in 2007 to 695, possibly because of the collapse of brick and mortar bookstores (manga publisher Tokyopop shut down temporarily within months of Borders).

Publishers, for their part, pointed fingers at scanlators. Japan’s Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry reported that 50% of U.S. manga and anime fans consumed pirated work. That’s about $20 billion in damages, they estimate. Worse, it is manga artists who suffer the more dire repercussions of rampant scanlation—it’s so harmful that, in 2010, Hellsing author Houta Hirano told his Twitter followers that he wanted his manga’s scanlators to contract a disease so incurable that doctors would “shit themselves laughing” when they died.

Chara, who has scanlated March Comes In Like A Lion, says she definitely does “not view most scanlating and even a lot of fansubbing in the same vein as piracy.” Despite the success of the manga’s recent anime adaptation, there is still no official English translation. “The core intent of scanlating is to produce a by-fans-for-fans production, for no profit,” she said.

In 2009, NJT received a cease-and-desist from Kodansha comics and obligingly wiped MangaHelpers clean. Now, its forums are still cluttered with translations for other pirates to use on their underground scanlation sites, but that’s all. No slick inked pages, no drawn-over speech bubbles.

To move forward with his mission to make manga translation better, faster and more accessible, he’d have to work from within the publishing system. He wanted to revolutionize the English-language manga industry with his intimate knowledge of the underground scene. But he had to convince publishers that his operation was clean—and that he and his rag-tag gang of manga fans had something to offer.

Shortly after the takedown, NJT and a MangaHelpers associate emerged from Tokyo’s Jimbocho subway station donning suits and briefcases. From there, they walked to the offices of Shueisha, which has owned about thirty percent of Japan’s manga market. With a speech scrawled out on notecards, NJT tried to convince a dozen of the behemoth publisher’s employees that he could help broker deals between them and his best pirate scanlator buddies to bring more manga overseas. He’d provide valuable data on American manga consumers. He’d share talent. Most importantly, he’d help Shueisha embrace digital publishing, MangaHelpers’ greatest asset over its brick-and-mortar competitors. In the end, NJT says, Shueisha declined, citing his long resume of piracy.

For scanlators making the leap from the darknet to the mainstream, a few issues are at play. First of all, irreverence for the rule of law looks bad. But say that a publisher managed to look past that and offered a gig—most manga translation jobs are freelance. Despite their size, both Viz and Kodansha primarily rely on freelancers, although the smaller hentai manga site Fakku has staff translators. Payment for these translation gigs can be slim, so translators might want a full-time job, too. NJT said he’s constantly fighting with publishers over his scanlators rates—and some ask his scanlators to translate entire volumes for $500 (and that’s for a translator, an editor, a proofreader, a letterer and a manager’s work). But in Kodansha editor Ben Applegate’s words, scanlators shot themselves in the foot here: “Whenever there’s a large group of people giving away their labor for free, it’s going to depress pay for those who are trying to do things legitimately.”

Few scanlators have found a way to market themselves to publishers, but those who are successful don’t regret trying. Around 2010, Jenny McKeon, who was in college, was scanlating girls’ love manga on an IRC for three hours each week. She was studying Japanese at the University of Massachusetts.

“It seemed totally impossible that any [girls’ love] would ever get licensed,” McKeon told me over Skype. It’s a niche lesbian fiction genre that spans from topics like the day-to-day of intimate female friendship to hardcore hentai.

Years later, McKeon entered the Manga Translation Battle, an official translation contest, which tasked her with My Ordinary Life’s English rendition. It’s a comedy about the mundanities and sillier moments of small-town Japanese life, and as a special challenge, it’s full of Japanese puns. She won, and as a prize, she broke in: Her My Ordinary Life translation, published by Vertical Comics, made it to the New York Times manga bestseller list’s number one spot.

McKeon’s views on scanlation did a 180 after more and more manga publishers brought her on for translation projects. “If scanlators and the people who read them are also motivated by passion about manga, I think it’d be great (this sounds like a cheesy shonen speech, God, sorry) if we could work together to support creators, get the series we love licensed, and make the industry better, instead of viewing each other as the enemy,” she told me over Skype.

Perhaps the greatest scanlation-to-riches success story is that of Fakku, the biggest English-language hentai manga publisher, which was originally a scrappy scanlation site. After founder Jacob Grady received a takedown notice from a huge Japanese publisher, he bravely reached out about negotiating a publishing deal. It worked. Now, Grady publishes manga like Shoujo Material that he originally scanlated with a staff of full-time translators.

Today, Grady says he’s not against scanlating, but that the scanlation industry is moving toward above-board labor as fans’ demands become clear: “I believe scanlation and fan-subbing have had a positive effect on the industry and have grown the market for anime and manga outside of Japan. That said, the reason scanlation and fan-subbing were necessary in the first place was because the market was not being served properly by our predecessors, but that has changed in recent years.”

It’s not just publishers who can make breaking in difficult. Although scanlators say they dearly love the manga they translate, sometimes, the fact that they’ve translated it illicitly makes publishers weary to spring for an official translation. It’s a catch-22: frustrated that English-speaking friends can’t enjoy their favorite manga, scanlators will translate and disseminate it over the internet. And yet, perhaps if they had waited a year or two longer, a publisher might have picked it up, it might have sold some copies and, most importantly, the manga’s artist could pad their pockets with fans’ money. And perhaps they could have had a hand in translating it officially, with real financial compensation.

27-year manga translation veteran Matt Thorn, who has translated everything from Nausicaa to Ranma ½ and has never scanlated, alleges that if a manga has a good and popular scanlation, publishers will think twice about contracting translators and licensing it (representatives from Viz Media and Kodansha confirmed that scanlations are a factor in licensing decisions). Over e-mail, she described scanlations as “a cancer in the body of global manga culture. Every scanlation drastically reduces the likelihood of a given title getting an official translation, because publishers are wary of trying to get people to buy something when they know there is a free alternative out there. Once a scanlation is put on the Net, it becomes a permanent fixture that not even the original scanlators can remove.”

Recently, McKeon noticed that her official translation of Miss Kobayashi’s Dragon Maid, which blew up after anime streaming service Crunchyroll simulcast the anime, isn’t even on the first page of Google search results for a translation. (The only outlier from the list of scanlations is the manga’s Wikipedia page.)

For his part, NJT is working to get publishers to pay translators livable wages for skilled labor. But he’s had little luck. Eventually, NJT hopes to have his own platform where he can channel money to artists’, publishers’ and translators’ hands, one that proves how big the demand for high-quality, well-translated manga is in the U.S. He wants to help make a Netflix for manga, explaining that “People want to purchase and pay for material. We just haven’t provided a service appealing to them yet.” The only way to beat pirates and support good manga is to provide a better experience, he says—one dedicated to timeliness, speed, quality, design, price and device access.

NJT’s big task is to fight against the cultural tides he helped create in the first place. His pitch: “Who else is better to work with than the people creating this kind of industry for you?”