On March 26, a top game development studio in Korea released an unusual statement about one of its employees: “The woman was mistaken in retweeting a tweet with the word ‘hannam,’” derogatory Korean slang for “disgusting men.” It continued, “In the aftermath of this incident, I promise that we will create preventative measures, including education, in a timely manner.”

A swarm of gamers had unearthed and publicized the Twitter profile of an artist at IMC Games while looking for feminism-sympathizers in the South Korean games industry. The artist hadn’t hurt anyone, hadn’t even set her bra on fire. All she’d done was follow a few feminist groups on Twitter and retweet a post using the slang term “hannam.” In response, her employer, IMC Games founder and CEO Kim Hakkyu, who is regarded as one of South Korea’s most influential game designers, launched a probe to investigate her alleged “anti-social ideology,” promising to remain “endlessly vigilant” so it wouldn’t happen again. The investigation, he explained, was a “sa sang gum jeung,” a verification of belief—the same word South Koreans used in the Korean War to verify a citizen was not a communist.

For two years, vigilante swarms of gamers have been picking through South Korean games professionals’ social media profiles, sniffing out the slightest hint of feminist ideology. Anything from innocuous Twitter “likes” to public pleas for gender equality have provoked harassment from these hostile freelance detectives. It doesn’t end at hate mail and online pile-ons; jobs have been put in jeopardy.

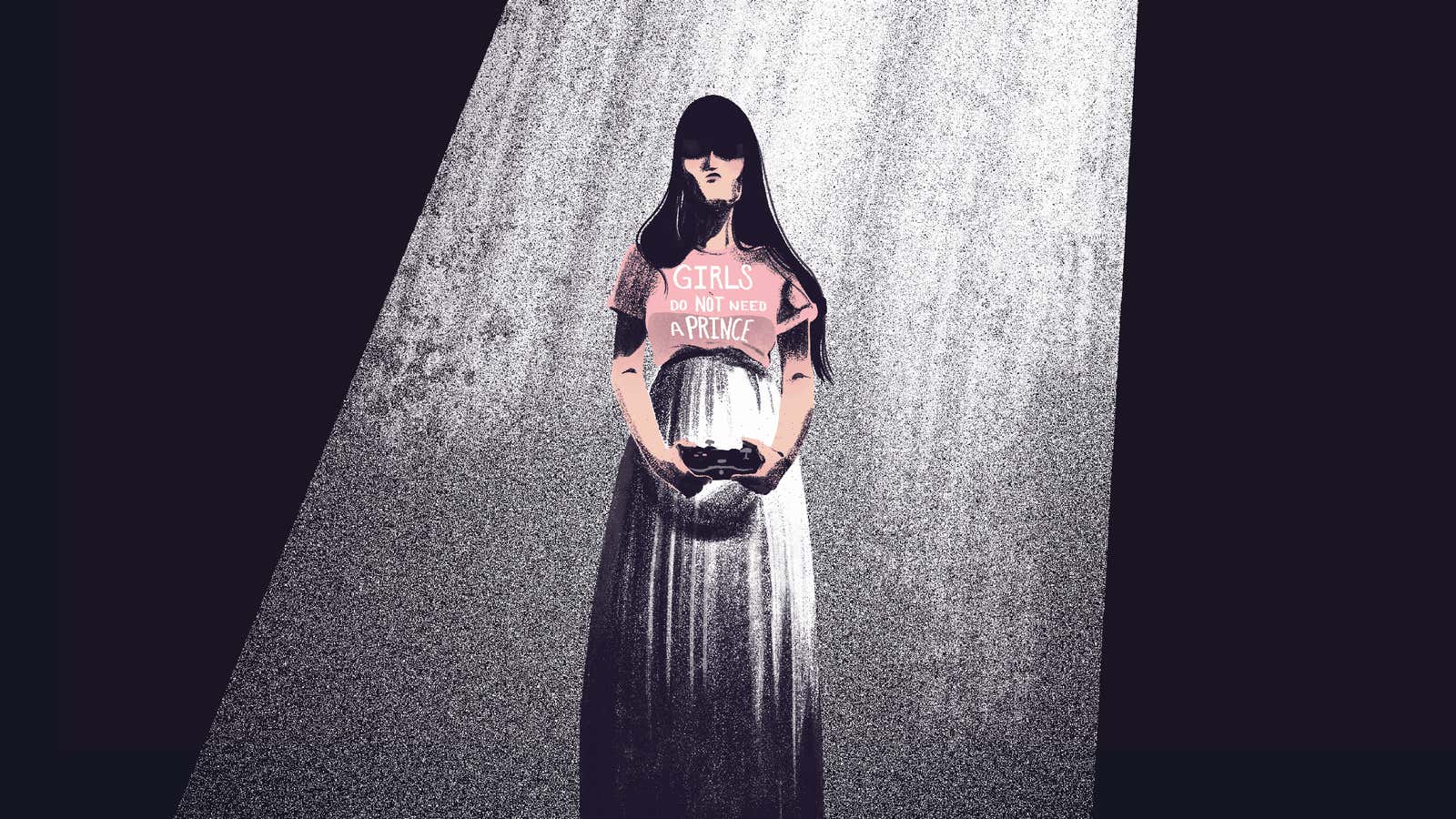

In 2016, the gaming company Nexon fired voice actress Jayeon Kim, who worked on the massively multiplayer online game Closers, after discovering she owned a shirt that reads, “Girls Do Not Need A Prince.” The shirt, and Kims’ employers’ response to it, sparked a controversy that echoed across the world. It wasn’t the women’s lib lingo that spurred the whole ordeal. The shirt was sold by affiliates of a controversial feminist website called “Megalia,” which, two years later, is still central to the ideological inquisition that’s consuming the South Korean games industry. Since the beginning of this year, anti-feminist gamers have tracked down and outed at least six other South Korean games professionals—both men and women—for allegedly aligning themselves with the radical feminist community that formed around the now-defunct website. The Korean Game Developers Guild claims that a total of 10 women, mostly illustrators, and 10 men have been under fire for these allegations.

Although Megalia’s userbase has dispersed, its reputation for radical, man-hating feminism seems to have overshadowed other pockets of feminist thought in the country. A lot of Megal advocacy is nothing out of the ordinary—posting signs reading “NO UTERUS, NO OPINION,” advocating against hidden camera pornography, and raising money for single mothers. A grassroots Megalia campaign helped shut down a child porn website.

That’s not what gets people talking. More radical users have also advocated for women pregnant with sons to get abortions and allegedly outed gay men married to women. A Megalia user’s post about a teacher who said she wanted to rape a kindergarten boy went viral. These users’ governing principle was to exact on men the kind of oppression they believe men have exacted upon women throughout history, so-called “mirroring.” Megalia’s reputation in South Korea is widely considered antisocial and radical. Uniting all affiliates is the Megalia logo, a hand with fingers separated by just an inch, mocking Korean mens’ penis sizes.

Nonprofits and human rights organizations have long noted South Korean women’s struggle for equality. The World Economic Forum’s Global Gender Gap index ranks Korea 118th on a list of 144 countries (the United States ranked 49th). Of 38 nations surveyed by the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, Korea has the largest wage gap between men and women. Women who receive abortions in Korea can be sent to prison or fined over a thousand dollars. After noting this, Human Rights Watch’s World Report on South Korea reads, “Discrimination against women is widespread in South Korea. Gender-based stereotypes concerning the role of women in the family and society are common—including widespread social stigma and discrimination against unmarried mothers—and are often unchallenged or even encouraged by the government.”

In Korea’s famously intense gaming sphere, which has produced top players for every big esports franchise, several instances of apparent gender discrimination in games indicate a severe, gender-based power imbalance. Although industry tracker Newzoo reports that 42% of gamers in South Korea are women, only a quarter of game developers are women, according to AFP. Top Korean esports teams spanning Starcraft, Overwatch and League of Legends have taken few steps toward including women, and when women do scale the ranks, they become targets.

When an impressive gameplay clip from a 17-year-old South Korean Overwatch player named Kim “Geguri” Se-yeon made the rounds last year, two pros publicly accused her of cheating. She made a video proving she was the real deal and, now, plays on the Overwatch League team Shanghai Dragons. Years earlier, South Korea’s first female Starcraft 2 pro, Kim “Eve” Shee-yoon, was brought onto a team “for her skills and looks,” according to her manager, and left after allegedly encountering sexual harassment.

The National D.va Association, now known as Famerz, formed from female Korean gamers’ desire to feel recognized and represented in a world where Korean women who play Overwatch are often told they’re “bitches” and “whores,” according to a Kotaku report on South Korea’s Overwatch culture. In Overwatch, D.va is a young Korean girl named Hana Song who, according to her lore, was a hugely famous professional gamer and operates a mech suit. “We get sexually harassed in gaming situations where it becomes known that we are female in voice chat,” said a representative for the Association named Anna. “Game streamers and male gamers are continuously coming up with new misogynistic buzzwords.” She cited “Song Hee Rong,” a portmanteau of D.va’s name “Song,” and “Hee Rong,” which, said together, sounds like Korea’s term for “sexual harassment.” It also references the Overwatch strategy of preventing D.va from regaining her mech suit after losing it, which, if considered abstractly, keeps her helpless.

After fans went after IMC Games’ concept artist, her boss Kim Hakkyu conducted an investigation and decided not to fire her. He did, however, publish an interview with her about the controversy. Hakkyu grills the artist on why she followed Megal-ish accounts like “Women’s Sisterhood” on Twitter. Kim admits she just wasn’t thinking about it that hard, citing her interest in improved access to menstrual pads. “Why did you tweet the word ‘hannam?’ ” he asks. “I didn’t retweet it because of the word ‘hannam,’” she responds. When he asks why she “pressed ‘like’ on a post containing violent Megalia opinions,” she responds, “I thought it was just that post. On the timeline, when there is a lot of writing, oftentimes they are hidden below. I only just learned that the hidden writing contained extreme opinions and I did not check back then before I pressed ‘like.’”

Hakkyu concluded, “She was mistaken in retweeting a tweet with the word ‘hannam,’ being unable to tell the difference between Megalia and feminism in its original definition.” (IMC Games did not return multiple requests for comment).

A week earlier, Korean anti-feminist vigilantes shone their spotlight on another woman in the South Korean games industry. The Chinese game Girls Frontline had hired a Korean character artist to make anthropomorphic guns for the mobile strategy game. K7, an unreleased character, is a stern girl with long, white hair, cat ears and thigh-high socks. Two hours after K7’s announcement, gamers dug through her creator’s tweets and Twitter “likes.” What they found was a comic parodying “hannam” she’d retweeted and another retweet about how women fear hidden cameras. The studio’s Korean branch immediately vowed to suspend K7. Its Chinese headquarters said they’d investigate the artist’s alleged “extreme tendencies,” adding that “So far, there has been no evidence that any K7 illustrator belongs to a certain extreme feminist organization.” Girls Frontline studio Sunborn Games has not responded to multiple requests for comment.

Around the same time, a swarm of anti-feminist gamers went after the male Korean game developer Somi, who made Replica, a left-leaning game critical of the Korean government, for liking and retweeting several tweets about sexual education in schools and offices. Thumbs-down reviews appeared on Replica’s Steam page, reading, “Megalia wild boars made this game” and “A top Korean feminist made this game.”

In solidarity, a friend of K7’s creator, who works at a tiny Korean games studio called Kiwiwalks, tweeted out her support for her disgraced industry colleague. That’s when, according to Kiwiwalks’ CEO, Girls Frontline community members proceeded to root through the friend’s tweets and discover that she, too, had retweeted tweets about women’s rights, specifically pertaining to abortion. That led to widespread calls for the illustrator’s dismissal.

A significant portion of Korean games developers and publishers who employ women targeted by anti-feminists have complied with critics’ calls to dismiss or rebuke employees. A plausible reason why shows up in the comments below games companies’ posts about the controversies: These critics are vocal about who they do and don’t want to be making their games. And these critics are also a large portion of their consumers. After two freelance illustrators on the failing Korean-made online game SoulWorkers were accused of having Megal-like Twitter feeds, and harassed as a result, SoulWorkers developers announced on March 26 that they’d replace the illustrations. They also said they’d begin “preliminary inspection” to make sure that these sort of “problems” didn’t occur in the future. In the next few days, a flood of new users overwhelmed SoulWorkers’ servers. It’s hard to prove causality, but SoulWorkers did seea 175% increase in players. Overwhelmed devs working around-the-clock to keep the servers up received box upon box of snacks, nutritional supplements and presents from players. (The illustrators have threatened legal action against their harassers.)

When I asked the Korean Game Developers’ Guild why developers are on board with these “ideological verifications,” a representative told me that, because men make up the majority of Korean games companies and most Korean games consumers are men—and because feminism and so-called anti-male Megalian feminism are conflated so often—shaming radical feminists is a lucrative business decision.

“The current market’s core consumers are men in their 40s and younger, and the game companies are forced to focus on their perception in reality,” the representative explained. They added that, “If you look at the response of the this subculture consumer group of men, it is assumed that they have established [the belief], ‘Since feminists are trying to suppress our freedoms with their ethics, we should grind the freedom out of them with our own ethics before that’ as a logical response.”

There has been some resistance to the anti-feminist attacks. Suyoung Jang, the CEO of Kiwiwalks, did something different from industry colleagues who buckled under consumer pressure to punish these alleged radical employees: He stated publicly that he would not investigate or dismiss his employee. In an email to Kotaku, he explained that “The employee did not take any action using the company’s account or name. She was simply retweeting about her individual interests on her personal account.” He continued, referencing Megalia, and adding:

“There is a growing number of men who respond very sensitively to even a simple remark about women’s rights. Especially among those who play games. But the content of the employee’s retweet was related to abortion. Even though there were some radical expressions aimed toward men mixed into that content, the issue of ‘abortion’ is one that any woman can relate/empathize with.”

After Kim Hakkyu’s interview with his employee, he wrote a summary of the conversation for readers and fans of his games. That way, they’ll know his stance on the issue of radical feminism and be assured of the preventative measures his company will take to ensure no such public ideological slip-ups will happen again. His employee’s Twitter activity, he said, “originated from ignorance or indifference to a very sensitive social issue.”

Additional reporting contributed by Kotaku social editor Seung Park.

Note: Several quotes in this article were originally written in Korean or Chinese but have been translated into English by speakers fluent in both languages.