In the 15 years I worked at Toys “R” Us, I sometimes leaked information about video game sales and posted them on message boards. I even took games home early to try them and then post impressions, which was very much against the rules. I did this because I’ve always been excited about video games and because, frankly, when your job is a grind, you will take chances if you know it’ll get your fellow gamers online to like you.

This piece originally appeared 10/25/16.

My path toward becoming a gaming rule-breaker began in 2000, when I started working for Toys “R” Us. In the early and mid-2000’s I worked exclusively in the store’s electronic department, known internally as R-Zone. I experienced the craze that is Black Friday (the first and only time I ever got knocked on my ass by customers) and the Christmas shopping season. From time to time, my job duties would expand, a sign that the company liked the work I was doing. Retail is one of the industries that has mastered the art of making added work feel like a reward. Raises are rare, just given out on the employee’s work anniversary. At one point I was given additional responsibilities that gave me access to more information at the company, including instructions for future sales advertisements—basically the ad customers would find in the Sunday paper.

Around this time, I also started to participate in online game discussions. I had disposable income, free time, and a lack of adult expenses, which gave me the opportunity to dive head first into gaming. But I didn’t have a lot of friends around me then, especially ones who enjoyed playing games. While I was able to buy systems and games for the first time in my life, I missed the excitement that came from talking about games with other people.

So in 2003 I ended up at the message boards of IGN. At the time they were a massive collection of sub-boards that covered video gaming, movies, sports, entertainment, and screaming into the void. Popularity on the boards had its own form of currency: the Watched User List, or WULs. The list was originally a way to keep track of users you enjoyed conversing with, but it also told the user how many people followed them. The higher the WUL number, the more famous, or infamous, a user was. WULs, as well as their post count, were prominent in community-driven posts called Member Updates. In some cases, you needed to be at a certain number of posts to even be on one of these lists.

I didn’t have much luck on the IGN boards. I would take the time to type out something of substance, only to see it be ignored because one of the community celebrities posted something close to me. My posts never seemed to get the recognition or acknowledgement I thought they deserved. I started treating message board posts like school papers, constantly checking for spelling and grammatical errors in an effort to make my point stand out. None of it seemed to make a difference, and my message board participation was just a one-way conversation.

But in October of 2003, something at my job presented an opportunity to get my foot in the door.

If you were a person who was buying a decent amount of games back in the first half of the 2000s, there’s a chance you’ve heard of Toys “R” Us’ annual “Buy two, get one free” sale on video games. Before the days of online shopping and price matching, this was the sale that benefitted the gaming consumer most. The sale was strategically positioned in October as a way to get people into the store before the holiday rush began and to help clear out some older inventory.

Sales and promotions the company ran were always played close the chest and kept from as many eyes as possible until the week prior to their start. Toys “R” Us was a market leader in the toy field, though at the time they were starting to see competition from Amazon, who were allowing other retailers to use their website as a storefront. Toys “R” Us would keep their sales secret so that competitors couldn’t run similar sales to try to undercut them.

I leaked the sale for the first time on October 1, 2003 in a post that revealed the sale would begin on October 26. The content of the post was slim. All I really had was the date, which I found out off-hand from a manager’s meeting, and the systems that would be eligible for the promotion. I trusted the information, though, so I tossed up the post on the old Gamecube General Board at IGN. I thought I was doing a service.

The first few people who commented in the thread took the information at face value and started to talk about which games they would pick up, but there were also people who had questions. I had approached the leak through the eyes of a sales associate, thinking about dealing face-to-face with customers who lived in a small community rather than the range of people I encountered online. Then, I learned that the information I had posted was partially wrong. The original date, October 26, ended up being for games for two of the three consoles, the PlayStation 2 and Xbox. The Gamecube games ended up being on sale the week prior, starting October 19.

Here I was, thinking I was doing a service and looking to garner some internet fame, and I looked like I’d screwed up. I couldn’t stop thinking about it: I was going to be one of those users who simply got ignored, or, worse, got called out for being a liar. I needed to find a way to save face.

I tapped Toys “R” Us’ Master Activity Planner, or MAP, to nail down what I was missing. The MAP was part of the company’s intranet that included detailed information on sales and other company-wide initiatives. I quickly learned the ins and outs of the ad process and picked the brains of more tenured staff. I learned the dates, about online sales, how Canadian stores were a different part of the company, and the ins and outs of the verbiage of the promotion. A couple days before the Gamecube sale started, I posted the new information I had collected in the thread.

My original suspicions were right: saving people money on video games would get them to notice you! Over the course of the sale I got private messages from users about how much money they’d saved or the cool games they’d gotten because they knew the sale was coming. It was an exciting new feeling. When I helped someone save money at work, it was solely to earn their trust so they’d continue shopping at our store. When I did it for these faceless folks on the internet, I got the personal pride of assisting someone who was a part of a community that I wanted to be a part of.

After that, I un-officially became the “TRU guy” (short for Toys “R” Us). I felt more accepted. I became a more active participant, and my posts got more attention. Every year when September rolled around, I would get bombarded with questions about the dates and details of the big sale. I happily obliged, and I posted the sale dates at IGN for several years.

In 2007, several users suggested that I share my information with a larger audience. So I decided to post the sale at Cheap Ass Gamer. CAG was known as the deals site. Their staff gathered all of the video game sales and promotions, leaked or otherwise, and presented them in an easy-to-read manner. The deals were posted on their message boards, and the best deals of the week were highlighted on the front page of the website. Their message boards also noted how many people viewed each thread. IGN only had the post count of a thread visible. Posting at CAG would let me see just how big my impact was.

The biggest draw to posting to CAG was that it was the site of the most famous retail leak in video game history, the first price drop of the PlayStation 3 via a Circuit City ad. That leak, and the threat of legal action from Circuit City afterwards, was a major news story at the time. Could my leaks get that big?

I posted for the first time at CAG in late September of that year. It was the lightest post I’d made in terms of content, but it was seen by more people than all of the sale posts I’d made prior to it combined. Its view count was well north of 150,000. The response was hugely positive, and I felt damn good about taking my leaks to the next level.

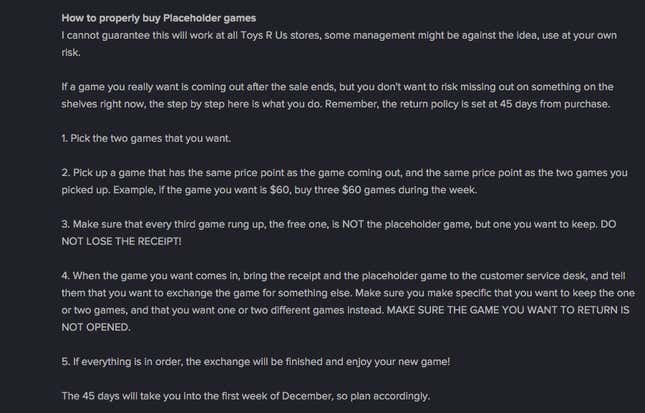

The next year, I put out the definitive FAQ of the promotion. Posted a mere nine days before the sale started, it appeared on the internet continually until the sales ended in 2013. It contained a detailed explanation of how the sale worked at the register. I also shared a placeholder strategy that my coworkers and I had come up with over the years to swap out games after the sale ended. My strategy involved encouraging consumers to return products after the sale. There wasn’t a process in place at the time to stop this from happening, but it definitely violated the terms of the promotion. Toys “R” Us would definitely not look too kindly on customers doing it, much less if they knew that store employees had put the idea in their heads.

During that holiday Toys “R” Us began looking for the person who had leaked the information. While I was talking to my store manager about video games, he casually asked me if I was the one leaking sale information to the internet. I was quiet for a long moment. I knew that if they had enough to figure out it was me, lying about it would do no good. I said as much to my manager.

To my surprise, my manager laughed. He said he suspected it was me from my writing style, but they didn’t have enough evidence to go forward with what would likely have been my termination. The store was a well-oiled machine in those years, and the management staff was close with the employees who worked hard. They didn’t want proof that I was the one doing the leaks because they didn’t want to have to let me go.

I knew I’d dodged a bullet, but I didn’t stop posting leaks to the internet. The attention and sense of belonging were just too good. Throughout 2009 I extended my posts to include vendor promotions. I announced dates of Pokémon downloads days before press releases and collaborated with others in retail to teach consumers how to find a Wii when demand was at its absolute greatest. But with the amount of people jumping in and turning leaking into a competition, I started to move away from posting about sales and promotions. It started to feel more like work, and I knew I needed to find the next new thing. Advance knowledge of sales was one thing, but what about advance impressions of the games themselves?

The nice thing about Toys “R” Us’ video game department was that it was a one person show most of the year. More people worked there during the Christmas holiday season. I had privacy and an intimate knowledge of the store security cameras, so I started taking new, unreleased games home before their on-sale street date. I’d slip the discs out of their cases and—to balance the karma of my actions and because I didn’t want to be called a thief—I’d slide the price of the game into the case. When the game was available for sale, I’d officially purchase it through the register and swap the sealed copy I’d bought with the one I’d opened a week prior. My unofficial sale became an official transaction. It was something that was against all company policies, but it seemed to work. I took home a few games and posted a few thoughts online. They were offhand affairs, one part information and two parts gloating.

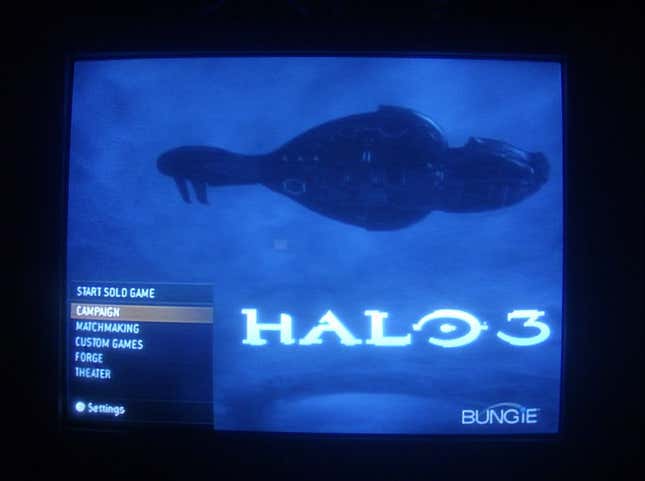

On the afternoon of Friday, September 14, 2007, the last shift before I took a long vacation, we received several boxes of Halo 3 for the Xbox 360. The game’s release date was September 25, and the major advertising blitz had just rolled out two days prior with the “Believe” commercial. It was unheard of to receive a game this early. With my upcoming vacation, I knew I was going to be able to play this game early, and a lot.

There was a problem, though: Xbox 360 games were sealed differently than PlayStation 2 titles. All video games have a plastic wrap that is vacuumed sealed. PS2 and Xbox 360 games also had a sticker on the case of the game to let the buyer know if the game had been opened. The sticker on a PS2 game was on the top of the case, so when I took those games I would slice open the side of the plastic wrap where the case opened, pop open the case enough to get my fingers inside, and pull the disc out. The top seal was kept intact, and the damage to the plastic wrap was barely visible. The Xbox 360 seal, though, was on the side of the case. That made it difficult to pop the disc out without doing considerable damage to the seal and plastic wrap.

I didn’t care. I had to play this game. I sliced into the case, pulled the Halo 3 disc out, and popped it into my pocket. I couldn’t get cash inside without damaging the plastic wrap more, but my excitement quickly overcame my trepidation. This time, I wasn’t entirely motivated by stepping up my presence in the online gaming community. There was also the edge of playing something that only a privileged few had access to and that so many people were looking forward to. If I was caught, I knew there was no way I could talk my way out of being terminated, but I couldn’t resist. The risk was worth it.

As I headed home with my prize, I realized another problem. This would be the first time that I played a game on an online service. No one at the store knew my Xbox Live Gamertag, but it could easily be traced back to me. I talked a lot of ill about my job, but in the end, I still loved it. I didn’t want to lose it, but I couldn’t pass up the opportunity.

I took my 360 offline and started playing the campaign. Eight hours later, I beat the game on normal difficulty. And then I did something I’d never done before. The next evening, I typed up something more substantial than my usual hints about pre-release games. I even took some pictures. I ended up posting the thread (the original thread is lost to the internet) on one of the smaller off-topic boards where I was a regular. The initial reaction from the community was the usual. A couple of the users posted how jealous they were, and the rest asked some questions.

But this time, word of me having the game leaked out to other boards at IGN. Soon names that I didn’t recognize were popping in with questions. My private message inbox filled up with demands. When I couldn’t answer everyone’s questions fast enough, some users started insulting me. I got so overwhelmed that I had to step away from the message boards and let things cool down.

I couldn’t stay away for long, though. I fleshed out my initial thoughts on the game some more, and a few days later I posted a more in-depth dive into the game. I also posted a review of the game using IGN’s now defunct Reader Review system, confusing some people into thinking it was IGN’s actual review. I spent the weekend before the game’s official release playing online with a small handful of others from England who had the game before people in the US.

Despite the stress and questions, it had been amazing to be maybe the first person to post Halo 3 impressions online. But once the game came out, traffic on my thread slowed to a halt. I wasn’t special now that everyone had the game. Attention turned to other commenters, and my high started to fade.

I found myself a strange mixed of sad and relieved, and I knew, especially given the risks I’d taken, that it might be time to hang up my hat. I no longer wanted to pursue internet fame. I would still take games home during the years that followed. The high of getting a copy of a game before everyone else was still there, but I never chased internet fame again.

The things I did were small in the grand scheme of things. I still take part in gaming discussions online, but its mostly at a private message board full of people who drifted away from IGN. The race to be the first with information has made its way to Twitter, and that is a competition I want no part of. The motivations of leakers today, though, are most likely just the same as they were then. I spent 15 years doing a job that the public boils down to stocking shelves and ringing a register. Even today, where there is a feeling of inadequate compensation and secret knowledge is placed in front of you, the leaks are not far behind.

Steven Ulakovich is Yinzer from Pittsburgh giving writing about what he loves a shot. He can be found on Twitter @GamingPessimist where he talks about Pittsburgh sports, video games, and professional wrestling.