For their groundbreaking Star Wars role-playing game Knights of the Old Republic, BioWare and LucasArts made the highly ambitious decision to have a cast of actors voice the game’s entire massive, branching script. That story, excerpted below, is told in the latest entry in the Boss Fight Books series, written by journalist Alex Kane and available this week.

With the exception of George Lucas, there’s one name that’s appeared in the credits of more Star Wars games than anyone else’s: Darragh O’Farrell. For more than two decades, he’s been the go-to voice-over (VO) director for Star Wars video game projects, in the LucasArts era and beyond.

O’Farrell was working in animation in Los Angeles, circa ’94, when he got wind that LucasArts was on the hunt for a VO director. “The company could see things were going from floppy disk to CD-ROM,” he says. “As a film company, they needed to embrace the talent side of things a little bit more, which is how I ended up starting there.” O’Farrell’s first game was The Dig, a 1995 point-and-click adventure adapted from a story by Steven Spielberg. It starred Robert Patrick, who’d played the villain in Terminator 2, and featured cutscenes by Lucasfilm’s renowned visual-effects studio, Industrial Light & Magic. “We were used to doing games that had like 10,000 lines of [recorded] dialogue, when no other company was really doing that at the time,” O’Farrell says.

What made the casting and sound departments at LucasArts unique, compared to other internal teams, was that they worked on all of the publisher’s titles. With Star Wars games, in particular, music and sound design has always been one of the key pillars holding the larger experience together. Knights of the Old Republic would be no different.

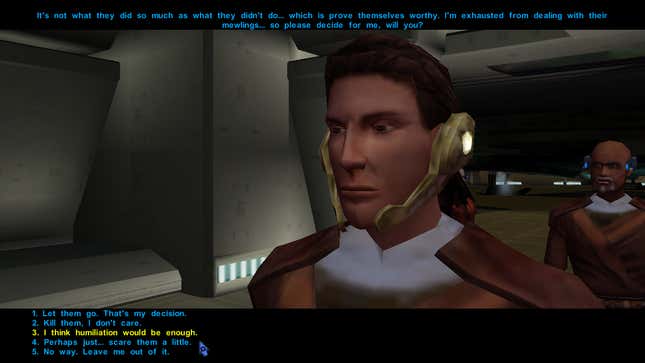

“We did want to have the BioWare DNA of story, and companion characters that you cared about, and choices that had impact,” lead designer James Ohlen recalls. “But we also knew this: We couldn’t do something that was text-heavy like Baldur’s Gate or Neverwinter Nights, because Star Wars is a very cinematic experience. And the fan expectations would be different than Dungeons & Dragons fans’ expectations. They’d be less understanding of walls of text and lots of reading, which is why [KotOR] was the first game where all of the non-player characters had full voice-over.”

O’Farrell remembers an early meeting with producer Mike Gallo and project director Casey Hudson, at which point the plan, he says, was still to do what BioWare had done in the past—a handful of spoken lines per interaction, with the majority of dialogue being displayed in text form. O’Farrell threw out a suggestion: “Why don’t we record the whole thing?”

Gallo and Hudson exchanged glances.

“We can do that?” said Hudson.

O’Farrell nodded. “As long as there’s room on the disc.” He told them he’d work on getting the budget approved; they still had about a year before it would be time to go into the studio.

“It was one of the most ambitious projects that LucasArts or BioWare had ever attempted,” Gallo says. “I don’t think BioWare had fully voiced anything in the same way that we were doing with this game. Certainly not that size. It was a huge budget for us, internally. It was a massive undertaking.”

LucasArts got its money’s worth, however. Pull up the IMDb entry on Knights of the Old Republic, and you’ll be greeted with a veritable who’s who of the voice-over industry. O’Farrell sent audition packets to a number of Hollywood agencies, casting the game largely with veteran actors from film, television, and previous LucasArts titles. A full paper copy of the game’s script could fill ten large binders; it called for about 300 speaking characters with roughly 15,000 lines of dialogue. Following a traditional casting process, a hundred or so actors filled those roles.

Recording took place at Screenmusic Studios, on Ventura Boulevard in Los Angeles, over the course of five grueling weeks. O’Farrell was joined by voice coordinator Jennifer Sloan, and the two of them worked numerous sixteen-hour days in order to ensure the audio was ready six months out from release.

The great challenge of recording a BioWare RPG became apparent almost immediately: The game’s structure was, for the most part, nonlinear. Every character, therefore, was given their own unique version of the script, and each actor had to be recorded individually. “The first week that I was in LA, James [Ohlen] was there, and he had his laptop, and every so often we’d get to a point where we weren’t quite sure which way the branching was going,” O’Farrell says. “And he would jump on and dig into the code a little bit, and then we would have a clearer direction.” In later weeks, writer Drew Karpyshyn also assisted with some of the sessions.

“That’s something a lot of the actors were doing for the first time,” Karpyshyn says. “So you really needed someone there to give them an overview of how the branching narrative works, and how the storylines are gonna play out, depending on player choices.”

“It’s probably one of the earliest games where I remember a character being both dark and light,” says Jennifer Hale, who voiced the Jedi Bastila Shan. “You know, having the ability to go in either direction. I remember doing a bunch of recording, and then coming back in for another round of recording, and them saying: ‘Okay, now basically she’s changing sides. She’s completely shifting.’ And I’m like, ‘Oh! Okay. Let’s do that.’”

The game’s many quest lines and relationships could develop in different ways based on what the player chose to say, or depending on which planets they journeyed to first. But the player character’s actions also affected their Force alignment; needless slaughter or malice could put a Jedi on the path to the dark side. Moral or immoral choices didn’t merely change the game’s ending but also altered the way companion characters, like Hale’s, responded to the protagonist.

The character of Bastila speaks with a British accent—“Coruscanti,” in the Star Wars universe. According to Hale, a Canadian-American actor, this is something that comes naturally. “I think in various dialects in my head, but British is definitely one of the primary ones, and that’s always been a part of me. Since I was little, and just in the back of my head—I don’t really know why. I just know it’s there. And I went to a fine-arts high school [where] we studied dialects. I’ve put in my time. I work with coaches every now and then when I need a tune-up.”

Hale’s commitment to her craft is evident to even casual fans of games. She holds the Guinness World Record for “most prolific” female video game voice actor, and has voiced characters as diverse as The Elder Scrolls Online’s Lyris Titanborn, Overwatch’s Ashe, and Mass Effect hero Commander Shepard (or “FemShep”), who had her own version of the Force-alignment continuum courtesy of that game’s Paragon–Renegade morality system. Tom Bissell, writing for The New Yorker, once called Hale “a kind of Meryl Streep of the form.”

“There’s no end of positives that you can say about Jennifer,” O’Farrell says. “Take somebody like Liam Neeson. Without him forcing it, you know, there’s a strength that Neeson gives off without actually having to overtly put it out there—it’s just the demeanor that’s there. There’s a strength behind it. And Jennifer has that, too. You just know that she’s not somebody you want to fuck with, you know? She’s a badass without having to be a badass. From a purely professional standpoint, she’s just a great actor. She makes sessions easy because she’s clued in and just gets it. So you can kind of jump in and start hammering out a lot of lines, and you’re just getting quality the whole time.”

Some of Hale’s earliest credits were, in fact, Star Wars games: X-Wing vs. TIE Fighter (1996), Force Commander (2000), Jedi Academy (2003). “I did a ton of games early on because, frankly, a lot of actors didn’t really want to do them because they were super demanding. And I just seemed to have a knack for it,” Hale says. “In the early 2000s, it was really exciting to be involved in the creation of games, and kind of at the forefront of some of the really powerful cinematic stuff that was going on, and especially as a woman. To be given these powerful roles, and a place to lead, and to occupy characters that were leaders, was phenomenal.”

The essence of the job, she says, “is really to go out and have as big a life as I can, and then to bring that experience into the booth.”

Bastila, a young Jedi grappling with both the enormous depth of her powers and her connection to Revan, is the emotional anchor of the game. Beyond Revan, she’s the beating heart of Knights of the Old Republic, and credit for much of the game’s resonance is due to Hale’s stellar work on the character.

One of the most contentious performances to come out of the production, oddly enough, was the beloved assassin droid HK-47, played by actor-director Kristoffer Tabori.

“Originally, [BioWare] wanted him really serious and evil and sinister,” O’Farrell recalls. “Because of our schedules, I was basically working nine to one, taking an hour, working two to six, and then at six o’clock I would do a session until ten, and I would just kind of eat, you know, while we were working. And Kris was one of those evening sessions.”

In the script, the character wasn’t played for laughs. A droid with a lust for violence, HK introduces almost every new line of dialogue with a tag denoting the mode of speech. (“Expletive: damnit, master, I am an assassination droid—not a dictionary!”) His voice is stilted, mechanical. He’s also utterly misanthropic, often referring to human beings, including the player character, as “organic meatbags.”

Tabori tried performing the part as written, but something was missing.

“After about twenty minutes we both, almost simultaneously, said, ‘You know, I’m just not feeling this. This isn’t quite working. I think we’ve got to play up the comedy angle,’” O’Farrell says. “And so we played around for five minutes with it, trying to sort of find the voice, and then decided, ‘Okay, we’ve settled on something.’ And we went back to the beginning of the script and recorded everything again, working our way through all of the HK-47 stuff.”

Usually, over the course of that five-week stretch, O’Farrell would fly into the Bay Area on Friday night and spend the weekend at home before returning to LA to record again. One week, however, he dropped by the LucasArts office on a Monday morning, and Mike Gallo stopped him in the hallway.

“We need to talk about HK-47,” Gallo said. “Everybody hates it.”

O’Farrell told him, “Mike, look, we tried to do what was on the character sheet. It wasn’t working. We went for the comedy route. I get that everybody might hate it right now, but you know what? We’re up against the gun. Let me finish the entire project, and then if there’s time at the end, we’ll talk about it.” Another month went by, and BioWare was forced to live with Tabori’s tongue-in-cheek version of the droid for the time being.

When O’Farrell got back from Los Angeles, and all the initial sessions were over, he asked, “What are we going to do with this HK-47 thing?”

“Oh, everybody loves it now,” Gallo insisted. “Everyone thinks it’s funny. We can’t cut funny.”