The end of the world was both darker and more humorous than anyone could have imagined, and in the original Fallout, released for the PC in 1997, gamers got to experience the apocalypse firsthand. The iconic, “War, war never changes,” introduction set the somber mood, which was written, strangely enough, during an episode of The Simpsons.

Tim Cain, who was the lead programmer and producer of Fallout, explained over an email interview that “my assistant producer, Fred Hatch, brought me the opening narration lines for the next day’s VO session with Ron Perlman. They had just been finalized that day, and Fred thought they weren’t very good. I read them and had similar concerns, so,” during commercial breaks, “I wrote an alternative opening narration. I thought about how war was a constant in human history and how the weapons of war changed, but the reasons for war and the goals of war did not.” He asked Hatch to “record both sets of lines the next day, and we would decide later which one we liked more.”

That mix of pop culture, looming deadlines, Ron Perlman, atomic bombs, and insights into the abscesses of human nature is the story of Fallout.

“Sometimes, the world is gray.”

I was torn by the moral ambiguities of the game. Unlike most RPGs, there were no pat moral choices or obvious divisions between good and evil. You, as the Vault Dweller, made decisions that affected how people reacted to you. Nothing exemplified the gaming branches more than the final boss, the Master.

Cain explained that “the genesis of the Master came about when we were talking about how the mutants would dip people into virus vats to make more mutants, and someone wondered aloud what would happen if more than one person was dipped at once. From there, it was a short jump to having a man and woman fall into the vat along with a computer terminal, and they merged into the creature that would become the Master. His goal was to save the world by making everyone immune to radiation like he and the other mutants were. And if it wasn’t for the one flaw the player could discover (mutants don’t reproduce), it could be argued that the Master’s plan was a good one.”

“We applied the multiple solution approach to the Master, and when we realized we had very clear multiple solutions (convincing him he was wrong, blowing up his base, or killing him in direct combat), we knew we were on the right track. The Master was fun to model and animate, and he was fun to write dialog for, too, since he spoke in a male voice, a female voice, and a synthetic computer voice. Explaining when the voice would switch to our audio director was fun, and when he understood the idea, he really liked it too. Then we knew we were right to make this our villain. Every department liked him.” He was a villain who “thought he was the hero.”

Dinosaurs and Time Travel

Until Fallout, most of the RPGs I played during the 90s had a fantasy element; Might and Magic, Ultima, Final Fantasy, and Dragon Quest. I remember installing Fallout and being enthralled by its futuristic setting. It was fascinating to learn from Cain that Fallout actually began as a fantasy game, a sample of which still exists on the Fallout disc.

That first iteration evolved into a game where you were “a detective looking for your girlfriend” who was “kidnapped by a cult. They sent you back in time, where you mess with history. There were dinosaurs, space travel, magic, and marauding princesses.” The scope was epic, including the assassination of the monkey who would evolve into humanity, and “spanned multiple genres, from film noir to fantasy to sci fi to alternative history. It would NEVER be made now,” Cain stated. “And I doubt it would have been made then.”

Still, Interplay liked “the idea of someone involved in a ‘save the world’ scenario, and we almost went with a storyline about an alien invasion.” Only one city remained on Earth from which you had to battle aliens and rescue humanity. That single surviving city eventually became the Vault, and the team decided they wanted to do a sequel to the classic game, Wasteland. When they couldn’t secure the license from EA, they were still in love with the post-apocalyptic setting, and Fallout came into being.

The small development team became a vault of its own, in part because Interplay was focused on the “D&D IP” which “was their big license, and with games like Descent to Undermountain and Baldur’s Gate in development, scant attention was paid to Fallout.”

That was a good thing in many ways: “Fallout was a rare development environment in that all of the people working on it were in agreement about the kind of game we were making and there was great communication between all of the departments. Artists and designers would talk about each area of the game as it was being made, and in many cases, the artists helped write the design. Programmers would talk to designers about different ways to achieve their goals, so often a design would be tweaked slightly to make it easier to code. And I enjoyed listening to ambient music while I coded, so I sent samples to our music director, who passed them on to Mark Morgan with suggestions on how to incorporate them into the game.”

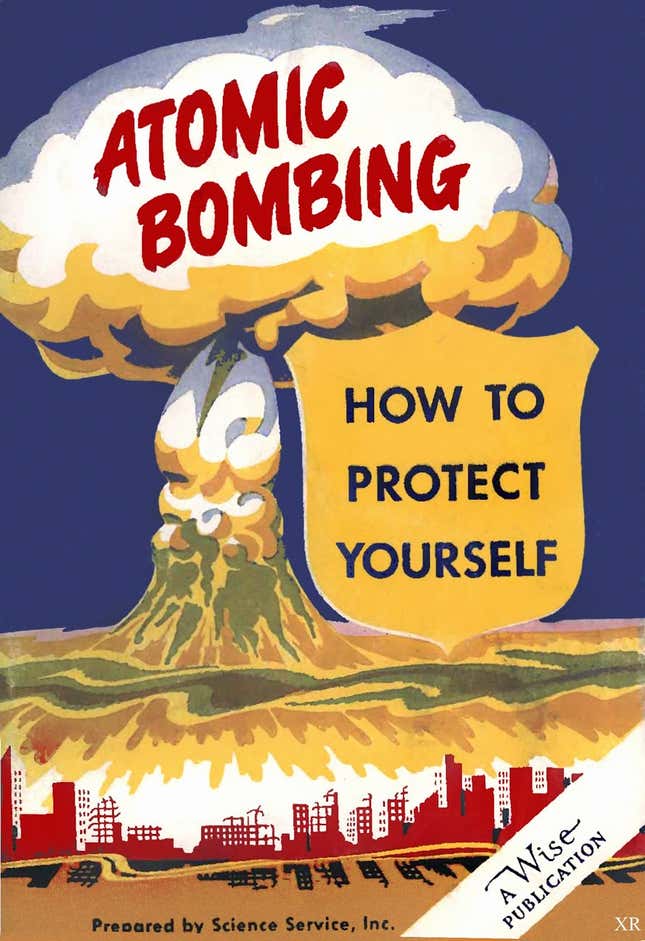

Could You Survive An Atomic Blast by Crawling Under Your Desk?

One of the most poignant elements of the game is the contrast of the dystopian world in ruins with the upbeat, retro 50s style advertising and technology. Cain explained how the inspiration for the visual style came from the “absurd optimism of government cold war posters from the 1950s.” It was because their lead artist, Leonard Boyarsky, “loved those posters. He was the one who suggested that the history of the Fallout universe diverge from our history in the 1950s. The idea was his that Fallout was the future that the 1950s thought would happen.”

That’s how the game’s aesthetic became less Terminator and more Robby the Robot from Forbidden Planet, which ironically, felt more ominous because of its “absurd optimism” in the face of cannibalism, extinction, and brutal nihilism. I still remember how real the threat of nuclear war felt growing up, especially as the Cold War had not yet ended. That pervasive sense that the world could end at any moment resulted in some of the works that influenced Fallout including A Boy and his Dog, Mad Max, and A Canticle for Leibowitz.

The allure of science fiction has always been its freedom to explore ideas with a different perspective, often illuminating the commonplace in strange ways. It’s also about pushing the characters to the extreme, not just mindless explosions and action sequences. In Fallout, the Vault Dweller is on a deadline. If he doesn’t find a water chip within 150 days, everyone in the Vault will die. But crossing the radioactive wastelands and navigating the junktowns of a devastated California takes time and that’s something you don’t have a whole lot of in the game.

Cain explained that Chris Taylor, the lead designer for Fallout, “was a big proponent of the time limit. He felt that a large open world like Fallout needed something to force the player to focus their attention on the storyline. We developed Fallout with the time limit, including adding cutscenes showing the water running out at the Vault. But many people didn’t like the time limit, including QA, and claimed the limit made them feel rushed and encouraged to ignore side quests. We shipped with the time limit, but it was one of the biggest complaints that early customers made, so we removed it with the first patch. Personally, I like open worlds with no time limits, since I like to wander and take my time and invent my own story. I know a lot of people like that experience too, but not everyone does. Some people like to have their story told to them, so a more directed experience is more to their liking. To each their own.”

A SPECIAL Game

Character creation was one of the most integral elements in the gameplay. The engine was originally based on a GURPS model, but the violence in the game caused Steve Jackson Games to withdraw the license. SPECIAL (Strength, Perception, Endurance, Charisma, Intelligence, Agility and Luck) took its place.

“There was not a lot of time to make SPECIAL,” Cain explained. “Chris Taylor and I talked about the systems it would have to support (code I had already written), which helped define what skills would be necessary to include in the game. He came up with the initial pass of attributes and skills, but I asked him to include the Luck attribute, so I could include its effect in many different systems. Also, after seeing the system, Brian Fargo suggested we have something else for the player to acquire when they leveled up, and Chris came up with the perk idea from that suggestion. That was most of SPECIAL right there, made in two weeks under intense pressure.”

I wondered if the game would be very different if GURPS hadn’t been there in the first place as a template. “It’s hard to say how Fallout would have turned out without GURPS. I think the area design would have been identical, but the combat systems were already in place, so SPECIAL had to tie into those. This meant we had to have a skill for unarmed combat, and we had to have one or more skills to heal damage. Interestingly, most of the tech skills were collapsed into a single skill called Science, since there were not a lot of opportunities to use all of the different skills. But by collapsing them, we made a well-used mega skill. The stats and skills all tie into specific parts of the game, either combat, dialog, or exploration, which Chris Taylor and I were in very close agreement about what needed to be covered. The skilldex, with its text and artwork, conveyed the dark humor of the game well, and showed the wonderful collaboration between design and art. The ‘vault boy’ has become an iconic emblem for the series. That character creation screen let the player know exactly what kind of game they were going to get.”

Conclusion

When I started Fallout, I only had glimmers of what awaited. The landscape of gaming has changed with its success and the Fallout series is still mesmerizing gamers with an alternative history that is as bleak as it is morbidly humorous. But all these years later, it’s that line, “War, war never changes,” that still haunts me. I asked Cain what some of the ideas he personally wanted to convey through the game were. “Don’t trust the government, big business and other authorities. Take responsibility for your own actions. Learn to predict and to accept the consequences of your actions. There are usually multiple ways to solve any problem.”

Fallout is a reminder of the future we need to avoid. There are many ways there. Let’s just hope there’s no deadline.

(An earlier version of this interview was published on TAY, the Kotaku reader-driven community. As TAY has gone the way of the dinosaur, I’ve updated and published here).