“Stories don’t have tidy beginnings,” says the main character of Heaven’s Vault, outer space archaeologist Aliya Elasra, at the beginning of the game. “The past is always present.”

I was immediately enthralled. I often see people hyper-simplifying history in bad faith and weaponizing it as propaganda, so I was excited to play a game that would expose history’s untidiness and get down in the muck with the ways people uncover, interpret, and rewrite history. For part of its duration, Heaven’s Vault’s heady yarn lived up to its opening and kept me hooked. But as I approached the end, the strings unraveled.

In Heaven’s Vault, an archaeology-based narrative adventure that came out on PC and PS4 today, you play as the aforementioned space-faring raider of tombs, Aliya. You’re tasked by your professor and basically-adoptive mom with tracking down Janniqi Renba, a roboticist from your erstwhile university who has gone missing. At first, Aliya is miffed at the assignment; why send a wayward archaeologist to hunt down a human being who’s ostensibly still breathing and not even close to a piece of ancient pottery? It quickly becomes apparent, though, that Renba has left a breadcrumb trail of ancient artifacts in his wake, all of which portend a grim future for a universe that has forgotten its past.

That’s a bummer for them, both in that a) everybody in this world is gonna die, and b) they’re all missing out on some really interesting history! The world of Heaven’s Vault is as intricate as any of those old Grecian urns that all the kids have been known to write odes to. It’s a ramshackle society reliant on ancient technology that has been stacked on top of a ruin stacked on top of countless older ruins stacked on top of a wellspring of intrigue. A series of outer space rivers span disparate planets, and only the truly bold—yourself included—dare to sail them.

Many of the residents of the wealthy, powerful, and more than a little oppressive moon of Iox think those outer space rivers are tied to a concept they believe in called The Loop, which is an eternal cycle of history repeating itself, complete with the same rises and falls. While your mentor, who lives on Iox, is All About That Loop, Aliya is extremely skeptical of her university’s dominant scientific theory/religion. She believes history is a tangled mess that must be studied and understood to inform the present, not to predict some neatly-packaged future that’s allegedly about to happen again and that just so happens to threaten the people in power.

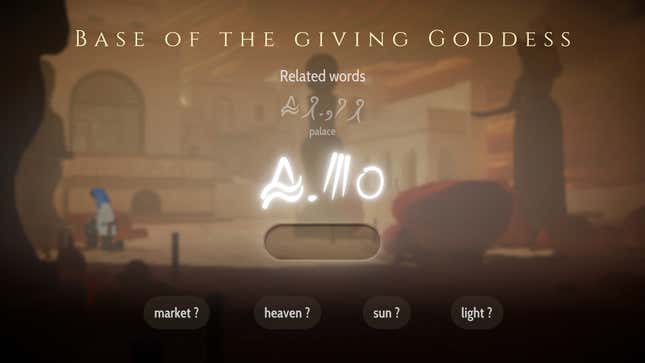

Aliya’s search takes her to a series of progressively more ancient sites in which she scrutinizes artifacts that contain snippets of a lost language. She has to translate these swirly-whirly runes using context, translations of previous runes, and no small amount of guesswork. This is where Heaven’s Vault shines brightest. Using scraps of language to create a patchwork quilt of historical happenings is a thrill—a slow-paced thrill, but a thrill nonetheless.

Initially, all you can do is take stabs in the dark with runes that are, thankfully, sometimes pictographic. Later on, you might find, say, a sword whose etching contains a word that you discovered on a door frame earlier, which confirms the meaning that you previously had only guessed was correct. That word’s meaning is then set in stone, and it feels goddamn fantastic. This only gets better with time, as you learn the ins and outs of the language and start to make more educated guesses. Heaven’s Vault is full of tiny revelations; I never would’ve thought one of my favorite gaming moments of the year would be realizing that a particular symbol denoted the past tense, but here I am.

These discoveries go into a massive timeline that spans the whole of history as you (and Aliya) now understand it, from the beginnings and ends of barely-understood eras, to what you did on the most recent planet you set foot upon. You can zoom in and out of this timeline whenever you want and re-translate old phrases. It’s a sleek, handy feature that helps you keep up with the game’s constant trickle of new information. That would all be tough to keep straight in your head without this tool, because, again, it spans thousands and thousands of years.

The game’s central plot plops satisfyingly into this ever-rippling pond surface of history, with conversations between characters informing your discoveries further. Sometimes all it takes is a conversation to add another speculative pin to the timeline or reveal a new location that you can travel to. Aliya’s robot companion, Six, ends up being your main sounding board for ideas, with conversations unfolding procedurally while you’re exploring, sailing between locations, or just chilling out on your ship. These conversations are affected by everything you’ve said and done previously and also the context of the location you’re currently at. It’s a really impressive system that ensures conversations almost always feel natural, even though they’re often doing the onerous dirty work of exposition.

Sometimes, these chats are simple. You can press Q to ask a question or R to make a statement. You can also opt to say nothing at all. Other times, you’re presented with a series of response options in the BioWare/Telltale/Alpha Protocol style, though it’s in these moments that the game begins to falter. Heaven’s Vault suffers from what I like to call “LA Noire Syndrome.” You might think you have a handle on what you want Aliya to say, but then—like noted yelly boy detective Cole Phelps—she blurts out something exceptionally rude or aggressive, and you don’t feel at all in sync with her anymore. Don’t get me wrong: I’m all for games where characters are more than puppets, where they have personalities of their own that sometimes buck against the player’s wishes. In Heaven’s Vault, though, it doesn’t feel intentional, but rather like the product of writing dialogue options that don’t appropriately telegraph Aliya’s emotional state. The writing, in general, has an unfortunate tendency to buckle under the game’s ambition. A couple exceptions aside, I found most of the central characters to be little more than thin archetypes in my playthrough, and many interesting ideas and themes fell by the wayside as the story picked up steam.

Part of this was due to the writing, as stated, but the game’s structure was also to blame. In another impressively ambitious twist for a game that’s almost entirely narrative-driven, you can tackle the whole thing in whatever order you like. You do this by sailing between locations on swirling space rivers. At first, it’s serene and enjoyable, given the sheer scale of the intergalactic vistas you’re sailing through. But it starts to feel like busywork when you’re circling general regions in search of the precise locations of new sites. The sites themselves are magnificent—ranging from verdant, populated forests to vast, abandoned craters that house technology humanity can no longer comprehend—but reaching them isn’t always enjoyable. Compounding this issue, the game sometimes straight up gives you the wrong directions. In the notes I took while playing the game, I wrote in a fit of rage that these sections felt like “trying to pick up somebody whose flight was delayed from the airport” because you’re just “going in repeated circles, praying that something will change.” I stand by this description.

This open-ended design does, however, lead to a tremendously impressive degree of choice. You really can progress through the game as you see fit. Maybe you want to press your nose to the breadcrumb trail left behind by missing roboticist Renba and follow wherever it leads. Maybe you want to chart your own course between planets and moons based on the more intriguing artifacts you’ve found. Maybe you want to cut a deal with a shady robot salesman for information about a long-forgotten observatory. Maybe you want to do this by selling off your own robot companion, a.k.a. one of the game’s central characters. Maybe you want to say “fuck that guy” (like I did) and find the observatory your own way. Maybe you want to report back to your mentor after every major discovery like a good not-quite-daughter. Maybe you don’t trust her, and you decide you don’t need her leads.

I didn’t find the big picture choice-based elements of the game to be as rewarding as I was hoping. For example, without spoiling too much, I’ll say that the game gave me what felt like a very credible reason to distrust my mentor-mom early on, so I decided to keep an artifact of history-rewriting significance I found from her, instead entrusting it to an engineer friend on my home planet for further study. This did not make my robot pal, Six, happy at all. Despite our burgeoning friendship, he was ultimately programmed to report back to my mentor. He literally did not have a choice. But I decided I wasn’t going to part with the artifact, especially while I was still trying to comprehend its inner workings. The first time I met with my mentor after acquiring this artifact, Six kept his mouth buttoned, or zipped, or however robot mouths work. Once we were back on my ship, however, he sent her a message, and after that, I got occasional notifications that she was expecting me to deliver the artifact. But then I just... never did. I had one more meeting with her after that in which she said I was becoming “unreliable,” but we never spoke again afterward. Then, hours later, I reached the end of the game without dropping off the artifact. This led, disappointingly, to nothing. I didn’t hear from Aliya’s mentor-mom in a post-game scene or anything like that. Their intriguingly strained relationship turned into a dead end. I never learned if I was right to distrust her or not.

The one character dynamic I mostly enjoyed was the frenemyship between Aliya and Six. At the game’s outset, Aliya doesn’t want Six around at all, and Six is a controlling dickbag (or dick bucket, or however robot dicks work) who hates poor people. However, I decided to take Six’s annoyingly frequent concerns about my safety into consideration rather than telling him off at every turn, and over time, he saw more of the universe and softened. Well, he softened a little. He never stopped contradicting me and my views, but he did it a little less frequently and a little more warmly. He was still in service to my mentor, but he was also becoming my friend. However, toward the end of the game, we had one conversation that, due to unclear choices, undid a lot of that goodwill and made me think that he actually hadn’t changed at all. Then, at the very end, he made a big decision that seemed to be influenced by my character’s choices. This would’ve been poignant, but it came out of nowhere given that, again, it didn’t previously seem like Six had come around to seeing the world my way. There was no real sense of progression to this character development. Just point A and point B, lying in nakedly stark contrast next to each other.

For all of Heaven’s Vault’s talk of untidy stories and warnings against people’s tendency to seek tidiness in history, institutions, and explanations for why the universe works the way it does, my playthrough ended on a note that was too tidy—too abrupt to feel earned. Meanwhile, the game’s story felt untidy in an unsatisfying way, a melting pot of themes and characters that ended up more shallow than they initially appeared. After beating the game, I unlocked a New Game+ mode that let me keep all my previous translations of ancient language. I’m interested in going back through and making a whole host of different choices, seeing if maybe Heaven’s Vault contains hidden depths I’ve yet to plumb. But I am not all that optimistic, given the number of things that I felt like I already saw to their respective conclusions. If nothing else, I’m absolutely stoked to translate more words. I think I’ve almost figured out how the ancient society did math!