In an earlier era of video game design, the most lucrative way to extract money from customers was to pulverize them into atomic dust and make them insert a quarter to reassemble themselves back into a humanoid shape.

Hard games never stopped coming out. What has changed about them, especially in recent years, is in how they have approached difficulty, and their interrogation of why we like a challenge. They have put the bottle of vinegar aside in favor of a jar of honey, in the hopes that more players will feel the satisfaction of winning rather than dwelling on the pain of losing.

It wasn’t always this way. The 1983 arcade game Dragon’s Lair was an exercise in psychic warfare. Nearly a decade later, The Simpsons was practically a mugging in slow motion, as were most beat-em-ups or shmups at the time. Sierra’s adventure games punished mistakes that nobody could have foreseen with impossible-to-escape dead ends. Early console games like Mega Man maintained an arcade mentality of limited lives and continues, despite the game coming in a fixed-price box.

These were hard and punitive games with harsh attitudes towards failure. Over time the landscape shifted and many of these harsh elements—the limited lives and continues, the dead ends, the obnoxious quarter-munching pitfalls—were phased out. Today, we still have tough games, but they mostly do without the castigation of their older analogues. Compare Mega Man 11, which gives players the option to never run out of lives, with the original Mega Man, which happily serves up an all-you-can-eat buffet of game-overs to intrepid players. Compare the 2017 adventure game Thimbleweed Park to the adventure games of the 80s and you will find an absence of dead ends leading to complete restarts. Beat-em-ups like last year’s Way of the Passive Fist have an array of checkpoints and difficulty options that set it apart from its older quarter-munching antecedents.

There exists an entire ocean of terrifically challenging games today, but they often offer quality-of-life improvements over the difficult games of days gone by. It may seem counterintuitive, but sometimes they can be outright gentle in their approaches to watching you fail hundreds or thousands of times.

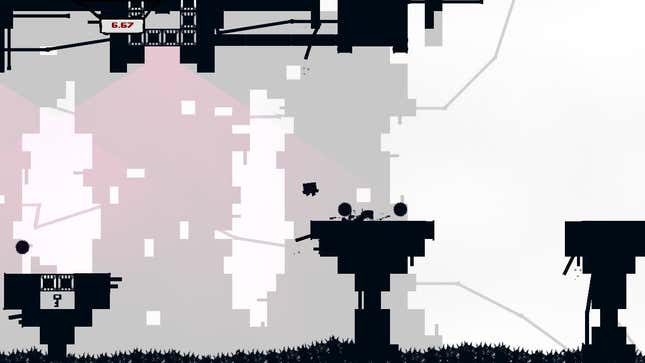

I can’t quite tell when the transition began. Like most shifts in media landscapes, it probably happened imperceptibly slowly. Super Meat Boy was released to widespread acclaim just over nine years ago. Its niche in the video game zeitgeist was in part due to the cresting wave of an indie game renaissance, but it was also talked about in terms of how sadistically hard it was. I think Meat Boy makes for as good a starting point to mark the transition as any, because it was surprisingly kind for a game of such difficult repute.

It was a precision platformer wherein you could die thousands of times before even making it to the deceptively-named Cotton Alley, where many diehards say that the real game starts. Yet it also didn’t limit your lives or continues. It killed you mercilessly, but then it did everything it could to make death less of a setback. The levels were often extremely short. The time between failing and jumping back into another attempt at a difficult level was negligible. The replays at the end of levels were also more rewarding than usual. Not only did overcoming an obstacle grant a rush of dopamine and adrenaline swirling together into a cocktail of satisfaction, but the end of a level brought with it a moment of catharsis watching the ghosts of all your different Meatboys painting every visible surface in ground beef until just one, representing the triumphant attempt, made it to the end of the level.

Even FromSoftware’s output has softened over time. In its 2009 PlayStation 3 game Demon’s Souls, not only does dying leave your valuable souls churning in a bloodstain on the ground where you died, your max health is also cut in half. The difficulty compounds upon itself in another way, too. Enemies can become stronger and more durable the more you die.

Its most recent game Sekiro: Shadows Die Twice is still heralded as being demanding, but offers you the chance to resurrect (sometimes more than once) when you lose your first health bar. When you do die, you are not penalized in nearly as harsh a manner. Compared to Demon’s Souls, Sekiro is practically a picnic.

A Rose By Any Other Name

Recent years have seen a sharp change in how difficulty options are presented as well. In practice, games are still mostly using easy, medium, and hard difficulty modes with various flavors in between, but what has changed is the framing, specifically in regards to the easiest modes of play. Deus Ex: Human Revolution is typical of the modern approach, framing its lowest level of challenge as being for players who aren’t interested in the stress of taxing combat simply by calling it “Tell Me A Story.”

In the past, games would often attempt to mock or emasculate the player for choosing lower difficulty settings. Cave Story calls you cowardly by outlining you in yellow for choosing easy mode. Alien Hominid’s easiest setting was called “thumb-sucker mode.” Wolfenstein 3D’s lowest difficulty was titled, “Can I play, Daddy?” and featured an icon of protagonist B.J. Blazkowicz in a baby bonnet. Serious Sam 2 almost got it right, calling its lowest difficulty “tourist mode,” but then it also turned your character into a pink-bonneted baby.

The difficulty settings of 2017's Wolfenstein II: The New Colossus harken back to the original, but it is no longer flanked by nearly as many games doing something similar. Most players probably wouldn’t call the bulk of Platinum’s games simple or easy, and yet this year’s Astral Chain featured a setting called “Unchained,” and the description for it uses similar language to that of Deus Ex: Human Revolution. It automates many of the game’s complex systems and offers unlimited revives. In fact, many of Platinum’s games have offered easy automatic modes without judgment, going back to Bayonetta at the start of the decade. Even fighting games like Dragon Ball FighterZ, King of Fighters XIV, and Killer Instinct have adopted auto-combos either as an immutable feature or a toggle.

While we’re talking about lending players a hand, Nintendo has been at the vanguard of this trend. Games like New Super Mario Bros. U and Donkey Kong Country: Tropical Freeze offer various types of assists that give you the option to skip troublesome levels. None of this is at the expense of including challenging late-game stages.

Just Breathe

Celeste, a hyper-difficult precision platformer, also launched with a feature similar to the ones just described. It was originally called “cheat mode,” but given that Celeste tells a story about overcoming mental health issues, panic attacks, and low self-esteem framed around climbing a mountain, designer Matt Thorson ultimately decided felt that the negative connotation of calling such a feature “cheating” was at odds with the story’s themes and renamed it to “assist mode.”

The functionality was the same, but the connotation was much more kind. That feature and its framing are not the only way this hyper-difficult game shows warmth to struggling players, though.

Why would anyone climb a mountain? Sure, there’s a spike of adrenaline and a natural high that accompanies the physical exertion. That doesn’t really provide a complete picture, though, does it? Mountain climbing is an act that also brings with it exhaustion, pain arcing through every sinew of muscle, and peril. The thrilling neurochemical high is temporary; it comes in fits and it washes in and out like a tide. If that was the singular reason for doing it, everyone would quit and descend down the second that euphoria gave way to pain and distress.

I think the reason that anyone completes a climb is for the sense of accomplishment when they crest the top, take a deep lungful of air, and look out over all of creation with a sense that through their own labor, they did something that the lactic acid in their muscles screamed at them that they couldn’t and shouldn’t do.

Rather than taunt, mock, frustrate, or revel in sadism, difficult games are now more focused than ever on encouraging players to reach the top of the mountain. Celeste, in particular, takes a very active role in encouraging you to reach the top.

“Just breathe.” “Why are you so nervous?” “You can do this.” Messages like these, delivered on postcards that arrive throughout the game, are meant to keep you moving forward. Odds are, you are going to fail a lot before beating the game for the first time. In fact, your death count is shown to you at the end of every stage. En route to beating the game (along with numerous B- and C-sides of stages), I racked up over 1,200 deaths. But Celeste wants you to get to the end so you can bask in the pride and accomplishment of overcoming it. The postcards reframe failure, and the one that most evinces that philosophy of encouragement reads: “Be proud of your death count! The more you die, the more you’re learning. Keep going!”

Last year, a game titled Death’s Gambit attempted to translate elements of FromSoftware’s playbook into 2D. That means, in part, you will likely die a lot over the course of a playthrough. Its developer White Rabbit accounted for that, adding a rather unique way of assuaging the frustration of failure by showing you a unique cutscene. These scenes don’t play after every death, but are triggered somewhat randomly and are unique to every other type of cutscene in the game. In a game in which you are expected to die often, these moments almost reward you for doing as the game expects, and they give you the opportunity to take a deep breath and let go of any lingering resentment over how you died.

Children of Morta, an underrated roguelite from this past October, employs a similar system. Failing to finish plumbing the depths of Mount Morta does not simply kick you back to the family manor where you began. Instead, you get to watch time pass, new events unfold, and the family bond and grow stronger together. The story moves forward incrementally whether you complete a run through the various stages or not. It makes the bitter pill of falling short to a difficult boss punctuating a grueling hour-long run a little sweeter to palate. The reward for success is greater, of course, but defeat isn’t quite as deflating compared to other games in the genre.

The nature of difficulty in games is in constant flux. This decade, challenging games didn’t lose their edge, but instead became more aware of the reasons why we enjoy difficult things and what the ultimate point of a challenge is. This decade, hard games became more gentle and more accessible.

David O’Keefe is a freelance journalist and photographer who smiles at the very mention of leopard geckos or Warcraft 3. As a result of his struggles with depression and social anxiety disorder, David has also become a vocal mental health advocate. He covers games, esports, tech, and entertainment. Follow him on Twitter @DaveScribbles.