Early September, 1999. Britney Spears dominated the airwaves, fear of the Y2K bug hung in the air, and my teenage mind was still wrestling with whether or not Phantom Menace was good. It had been about a week since I had returned from a summer trip to Taiwan to my home in Atlanta. A couple of my friends who I hadn’t seen all summer had come to my house, waiting to see what strange wonders I had brought back from the East.

“I don’t know if you guys are ready for this.”

“Joe, we’ve been playing video games all our lives. I think we can handle it.”

I turned on my PlayStation. Two cheap plastic mats, connected to the console, laid on my floor. They crinkled underneath my feet as I took my position.

“What is that,” one asked. “Did they remake the Power Pad or something? I’m not in a mood to work up a sweat right now!”

I told my friends that there would be scrolling arrows on the screen, and once those coincided with the static arrows at the top, that would be their cue to tap on the corresponding arrows on the plastic mats. I set the song to Smile.dk’s “Butterfly,” my go-to track for introducing newcomers to the wonders of Dance Dance Revolution.

The first of my friends to brave this foreign contraption struggled to read the directions on the screen and simultaneously translate them into orders for his feet. It wasn’t long before his brain had the “eureka” moment and he began to understand.

“I can do better. Let’s go again.”

In the course of one afternoon, I got my friends hooked on a game that wouldn’t come to the American PlayStation for another two years. Word started to spread about this weird Japanese game that Joe brought back from Taiwan. With this new marquee attraction, my basement became a premiere hang-out spot.

This role of the wandering trader, trekking through the videogame Silk Road to pick up the oddities from one region and share them with another, was something that took its roots back in my elementary-school days.

Once upon a time, before the advent of social media and YouTube, the divide between the American gamer and Japanese gamer was shrouded in a thick fog that would make John Carpenter’s knees buckle. American gaming magazines covered some Japanese imports, but barely scratched the surface of what was available. While I was a Taiwanese-American that had never actually been to Japan, the video game scene in Taiwan was quite similar.

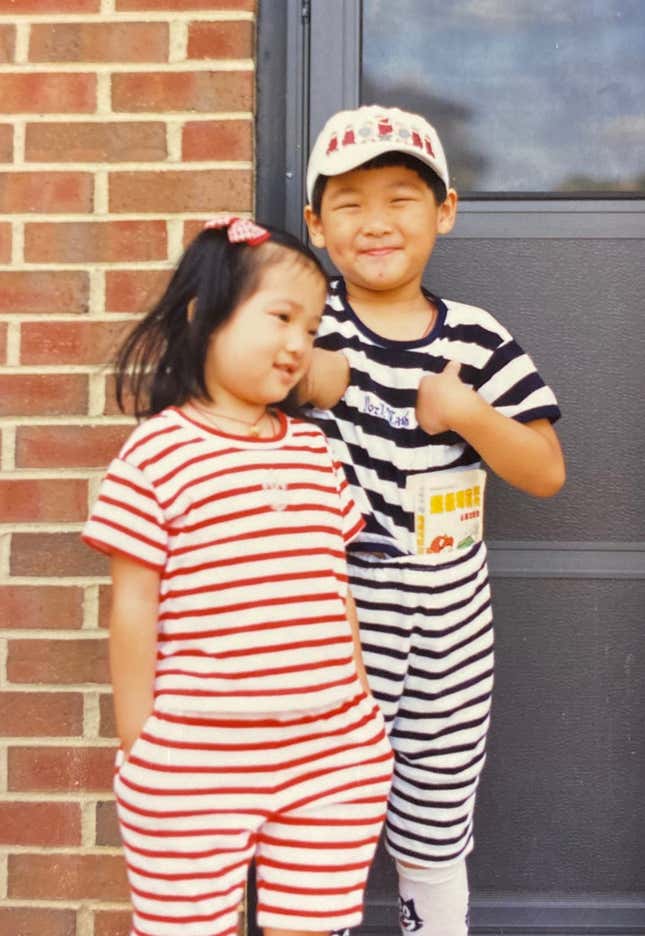

My parents had emigrated to America in 1986 so my dad could pursue a medical degree. Later, he added a Masters to that, attending a university in Nashville. My family’s tiny Tennessee apartment was technically a dorm, part of a small cluster of university apartments reserved for students with children.

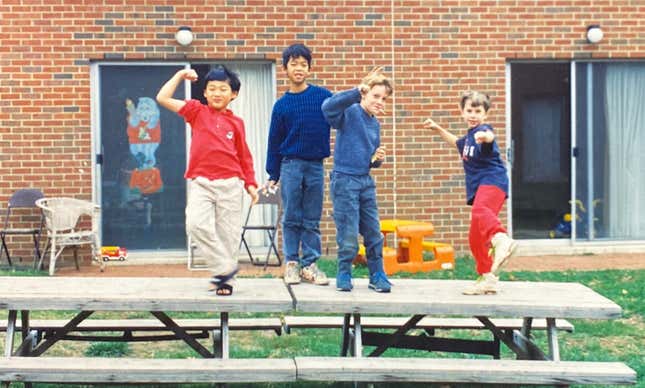

The best feature of these tiny apartments was that they shared a communal backyard. For me, this meant there was never a shortage of other kids to play with. It was also an incredible opportunity to be exposed to a rich tapestry of various cultures, due to the huge presence of international students. And also a rich tapestry of gaming machines from around the world.

A couple of kids had Nintendo Entertainment Systems, of course. But others had the Japanese version, the Famicom. There were some Game Boys and Game Gears peppered throughout. We even had an Atari 2600.

Every day, after we exhausted ourselves from running around outside, the kids would all converge on one apartment to play video games. (Every single apartment had the exact same layout, and for whatever reason, every household had the same room on the second floor delegated as the “playroom.” A natural feng shui, I suppose.)

The premiere games of this era were the ones for the NES and Famicom. We didn’t know why there were two different versions of the same machine. We figured it was like how one family used chopsticks and another family used forks. Some kids used a Famicom to play Mario, some kids used an NES.

And we all had different game libraries, of course. At the time, we assumed that I had games like Battle City, Devil World, Goonies, and Nuts & Milk because those just happened to be the ones that my parents bought for me. We didn’t know that I had these games, and other kids didn’t, because they were never released in the U.S. It was only the Mario series that made us realize that there was something fishy going on.

Before I continue, there are some details I have to divulge. One of my aunts in Taiwan was a huge gamer. Every few months, she would send a care package to us containing some Taiwanese snacks, random household goods, some VHS tapes of Taiwanese variety shows, and, most importantly, a bootlegged Famicom cartridge that would contain, at a minimum, 24 games.

Now, sometimes those games were just hacked versions of other games. One cartridge purported to include Contra 2, 3, and 4, but they were just Contra 1 with various power-ups permanently activated.

So one day, when another kid said he’d rented Super Mario Bros. 2 and invited everyone to check it out, I wasn’t that excited. I had already played Super Mario 2, and dismissed it. It looked almost identical to the original, had all the same music, and was ridiculously difficult. It also had mushrooms that killed you, completely betraying the trust forged in the first game between game and gamer.

“That game isn’t fun at all,” I said to the room. “Let’s play something else!”

“Pfft, no way! You’re probably just not good at it!”

Over my protestations, they turned the game on. But something was weird. The title screen looked totally different from what I remembered. When the character select screen popped up, allowing the player to choose between Mario, Luigi, the Princess, and Toad, I could barely compute what was going on. This wasn’t the SMB 2 that I knew! The graphics were more vibrant, there was a whole new jolly soundtrack, and you could pull vegetables from the ground and throw them at a whole new group of enemies! I was transfixed at what was happening on screen.

Later on, when I got home, I concluded that my SMB 2 must have been one of the crappy modded bootleg sequels, just like the so-called Contras 2 through 4. It wasn’t until Super Mario All-Stars on the SNES that I realized I’d been playing the original Japanese version all along.

Not too long after, a couple of us watched the 1989 movie The Wizard. In retrospect, this movie was a shameless giant commercial for Nintendo and Universal Studios. But at that time, it was the only movie where video games were front and center. It also showed a bunch of kids, on a road trip to a video game tournament, without parental supervision, doing whatever the hell they wanted. A kid’s dream.

The climactic reveal was the final game of the tournament: Super Mario Bros. 3, which was not yet available in the U.S. The tournament’s host practically frothed at the mouth announcing the game, manically strutting back and forth on the stage as the contestants played. In theaters across the country, kids got their first glimpse at the next Mario game and collectively lost their minds.

As all this excitement unfolded onscreen and offscreen, I was just thinking: “Oh yeah, it’s that game I have at home.”

Super Mario 3 was just another title in our communal library in the university apartments. Years later, I would hear about the anguishing wait for SMB 3 to be released stateside, and then the second phase of this real-life boss fight: trying to track it down on store shelves.

At this point, the unique experience of being Asian American wasn’t something I had fully grasped yet. It still only amounted to me having a different kind of lunch from my friends at school and knowing one more language than most of my classmates. It wouldn’t be until middle school before I realized I was Hannah Montana, getting the best of both worlds.

In middle school, I met this kid named Jeff. He was also Taiwanese American, a math genius, and a piano prodigy. His mom ran Kumon after Chinese school on Saturdays. Chinese school was a sixth day of academia for most Taiwanese Americans growing up in the 90s. At our school, we’d spend a few minutes learning Mandarin, and then an hour or two hanging out with friends from different school systems, sharing hand-written move sheets for fatalities in Mortal Kombat II.

Jeff’s family and my family were in the same parent clique and we would gather at each other’s houses once a week so our parents could belt out karaoke on a laserdisc system until the late hours of the night.

Whenever the party would rotate to Jeff’s house, we would get to play with his Super Famicom and his massive collection of games. But his collection was not, for the most part, composed of official gray cartridges. Instead, it was a library of multicolored floppy disks. Jeff had a massive add-on that was thicker than the Super Famicom itself. Once you connected this contraption via the cartridge slot, it would boot up games from a standard 3.5 inch floppy disk.

When it came to official games, his collection was largely Japanese Super Famicom cartridges. The only American Super Nintendo game he had was Final Fantasy III, and to get it to fit into the more rounded slot on the Super Famicom, he had to physically cut the sides off of the cartridge. I looked at the massacred grey body of this SNES cartridge and cringed. Games were crazy expensive back in the day, and to physically remove chunks of one seemed unreasonable and cruel.

Playing Jeff’s copy of Final Fantasy III gave me the Japanese role-playing game bug. It wasn’t long after that I bought Chrono Trigger. I absolutely adored these games’ soundtracks. In the back of certain issues of GamePro magazine, there would be ads where you could order these multi-disc beauties that were exorbitantly priced. My middle school finances did not afford me these luxuries. However, I knew one of my bi-yearly Taiwan trips was coming up and gaming merchandise there was always leaps and bounds better than what was available in America at the time.

In the midst of the Ximen shopping district in Taipei was a building called “Ten Thousand Years.” It was multiple floors of amazing small shops that catered to youth fashion, anime collectibles, and video games. My target was the soundtrack to Final Fantasy III.

Little did I know that I was about to be confronted by another bombshell. As far as most Americans were concerned, Final Fantasy III was the most recent release. Yet, there I stood, looking at the soundtrack for Final Fantasy IV, a disc with the subtitle Celtic Moon. Did Japan have unique subtitled names for their Final Fantasy games? I flicked away from that CD and saw the soundtrack to Final Fantasy V. What was happening?!

After a short bout of confusion, I surmised that what I was actually looking for was the soundtrack to Final Fantasy VI, thanks to the Magitek armor in its logo. But I still left the store in a state of betrayal and confusion. If what I knew as Final Fantasy III was actually the sixth game, what about IV and V? What even were those?

Back in the States, my friends weren’t as blown away by this mystery, because they didn’t actually care. Most of them didn’t even know what RPG stood for. Even after Final Fantasy VII converted them into RPG fans, when I got my hands on the Japanese version of Final Fantasy VIII, what started as excitement quickly melted away into boredom when none of us could decipher the language. Fortunately, my discovery of Dance Dance Revolution a few months later was better received.

The PlayStation 1 era was truly the last time that I could delight my friends with oddities from overseas. It was at this time that gaming sites on the Internet started to come into their own, bringing wider access to Japanese gaming information. Games like Ore no Ryori (a dual-analog controller-only game that tasked you with juggling multiple food orders that also had an addictive multiplayer component) and Poy Poy (a simultaneous four-player arena battle game where the objective was to be the last man standing) entertained as much as it confounded my friends.

The care packages from my gamer aunt continued to roll in through the years. Every so often, she would send me games that she thought were must-plays. One, in particular, stood out: Pepsiman.

Initially when I tried to play this PlayStation 1 action game myself, I didn’t make it past the first cut-scene. I watched a weird, live-action short of an out-of-shape man in front of a vending machine, trying to quench his thirst. I immediately swapped out the game.

Often, when friends were browsing my game collection, they’d land on Pepsiman and I’d just dismiss it as some dumb promotional game. At some point, a friend just went ahead and popped the game into the PlayStation, taking us all on a magical ride.

Once again, the sheer weirdness and addicting gameplay just sucked us in. We didn’t know whether or not Pepsiman was a full-fledged, officially licensed, studio-developed game, or if it was just some random game someone whipped up in their spare time. We had so many questions and so few resources to find answers. The feeling wouldn’t last. These days, you can find out about anything in seconds, and it’s actually weird if a major game doesn’t have a global release.

As I reminisce over these anecdotes of donning the guise of a carnival barker and inviting my friends to check out the strange wonders I’ve collected from my other home country, I can’t help but recognize the role video games have played in the forging of my Asian-American identity.

Acting as a conduit between these two cultures was a role I took in stride, and gaming was one of the mediums that allowed me to take on the responsibility. While the modern conveniences and informational power granted to us is fantastic, a small part of me does wax nostalgic about the days of stumbling blind onto a cross-cultural gaming discovery and uncovering its mysteries.

Joe Shieh loves video games and movies but not video game movies.