Editor’s note: This piece contains minor spoilers for Fire Emblem: Three Houses characters Marianne, Bernadetta, and Claude, as well as descriptions of emotional abuse.

In Fire Emblem: Three Houses, there’s a character in Golden Deer house named Marianne. She’s so shy that she barely speaks. At first, I thought this was a confidence problem. I eagerly gave her gifts, not just to get to her next support rank and trigger a new conversation, but because being nice to someone who was clearly struggling felt like the least I could do.

As she got closer to other characters, though, something darker shone through. When Lysithea scolded her for not jumping to action when other students were involved in an accident, she ran away and retreated to her room. Lysithea went after her to apologize for being too harsh, but Marianne insisted that it was, in fact, all her own fault. She went even further than Lysithea, saying increasingly disparaging things about herself as Lysithea tried to calm her down. As I watched this scene unfold, the feelings felt uncomfortably familiar. As these characters acted through and reckoned with their trauma, it ultimately helped in my own journey to healing.The last time I left an abusive relationship, I had been struggling to breathe for what seemed like months.

He was a nice enough guy. We met on the internet when I was in a pretty vulnerable place—fresh out of a breakup, drinking too much, looking for warmth in the bodies of others. After a few conversations, he declared that we were dating. I was too tired to disagree.

My fatigue was a trend in our relationship. Visiting him once, he wanted to go to a pizza place that was a fair walk from our train stop. We had been out all day, and my feet were aching. I asked for a rest, I asked how long it would be, I asked if there was a bus nearby. There was no alternative plan—my pain seemed to bother him more than anything else. I walked until my feet felt like two inert stumps at the end of my legs. Afterward, he got a bucket of water for me to soak my feet in. It was ice cold, and somehow my shock it its frigidity felt like my fault too.

I told him that it made me so anxious to get messages that said, “we need to talk.” He would read to me on the phone every night. If he saw me tweet after saying goodnight and hanging up with him, he’d send me a message. I’d stay up all night wondering why he was upset, only to have a talk the next day that amounted to, “Well, if you say you’re going to bed, I assume you’re going to bed.” It was his delivery, I said, that made his comments difficult for me. He heard that criticism, he said, and wouldn’t do it again.

He did do it again. He did it a lot. More and more often, the messages he left me were angry. I was exhausted every day, barely sleeping, wondering what I could do to make this man less upset. It was like running uphill all day, trying to reach a goal of “making him happy” that seemed to keep moving further into the distance. My legs burned and my breath was hot and ragged, but I kept running.

Now, in the last year of my 20s, I would have broken up with this guy before we had even gotten started. Almost half a decade ago, this was just how I assumed men were supposed to treat you.

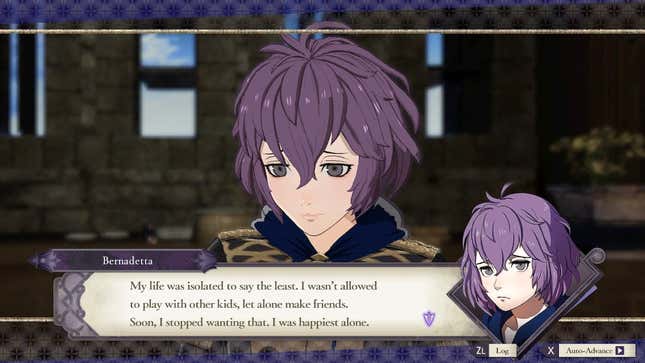

Marianne’s persistent self-loathing resonated with me as I continued through Fire Emblem, but as the game went on, I discovered that she’s far from the only character whose home life was less than pleasant. The Black Eagles’ Bernadetta is so anxious she barely leaves her room. In an early support conversation, I learned that her father sometimes resorted to tying to her a chair to train her to be a perfect, silent wife. She didn’t come to Garreg Mach by choice—she had been kidnapped by her parents in the middle of the night. The actual circumstances of these abuses fit well enough in Fire Emblem’s fantasy world that they don’t feel totally analogous to my own life, but seeing characters with the impact of these traumas written into their every action rang true.

The pain that Marianne and Bernadetta’s families have inflicted on them is too deeply ingrained for them to come out of their shells easily. They believe that they are worthless because their parents told them they were. When someone you hold as closely as a parent or a partner spends so much time telling you or showing you that you are worthless, you believe it.

Though Bernadetta’s social anxiety is sometimes played for laughs, the subtext of those same jokes is that she is deeply afraid of other people. Usually the jokes subside when the other character realizes why she’s so nervous, which softens the edges on the game’s humor. I never felt like a joke was being told on Bernadetta. Her peers just didn’t understand her. These conversations are the journey to that understanding.

Bernadetta is afraid that they are angry at her, because her father was so often angry at her and punished her severely for not living up to his expectations. We don’t see the abuse happening, but we see the product of it. Bernadetta doesn’t just lack confidence; she expects to be abused.

When you interface with characters who have been abused in this way, it humanizes the characters more strongly than showing the disturbing acts themselves. I don’t want to see Bernadetta being berated by her father—I can already see what the pressure he put on her has done to her.

I’m in the best relationship of my life, so it seemed like a good time to read Why Does He Do That by Lundy Bancroft, a seminal text about abuse.

I read this passage and recognized myself:

“Sometimes [control] is exercised through wearing the woman down with constant low-level complaints, rather than through yelling or barking orders,” the book read. “The abuser may repeatedly make negative comments about one of his partner’s friends, for examples, so she gradually stop seeing her acquaintance to save herself the hassle. In fact, she may believe it was her own decision, not noticing how her abuser pressured her into it.”

Eventually, with the man who never let me sleep, I stopped tweeting after saying goodnight to him on the phone. I stopped going out—how could I, when my partner expected to have a weekly stream with me, a date night for just the two of us, a very long session of a tabletop roleplaying game with our friends, and also to read me to bed every night? If I invited my own friends to any of these activities, even the stream which was hosted on my channel, my boyfriend would get quiet. He wasn’t mad, you see—he just wished he’d had more warning. I stopped asking them.

I shouldn’t have dated this man for a minute, nor the man I dated in college who ignored my sexual boundaries, nor the man I dated before I’d recovered from that. They all primed me for each other, for shutting up and changing myself, for making compromises but never receiving them. I shouldn’t have dated three men in a row who had absolutely no interest in my friends. I am still proud for breaking up with all of them.

Getting to know Bernadetta and Marianne has helped me see myself more clearly. I see myself in Marianne’s shame, and in Bernadetta’s fear. I also see myself in their recovery.

In Claude and Marianne’s A-rank support conversation, he tells her a story. He’s been pestering her about her Crest, but Marianne is uncomfortable talking about it. In this last conversation, he tries a different way to get through to her without scaring her. When he begins, “Once upon a time,” she’s surprised, even though she was just talking out loud to a horse.

Claude presses on, telling the story of a “young boy who was hated just for existing.” Claude Von Reigan is mixed race, and the countries his families belong to hate each other. As a child, Claude had abuse hurled at him from all sides—from his father’s family for being the child of a coward, and from his mother’s side for being a member of a bestial race. Even running away from home didn’t help. He encountered the same prejudice everywhere.

“The point is, people are born with burdens to carry. That much is undeniable,” Claude says. “But whether they bind us or we cast them aside…that’s up to us. I think you should cast yours aside, Marianne. Put that heavy burden down. It’s time.”

Marianne says she wouldn’t know how, but Claude insists.

“It’s OK,” he says. “I’m here for you. We’re the same and…I can help you.”

Eventually, Marianne said in a cutscene that she was through with being afraid. Maybe she was anxious; maybe she didn’t like herself all the way, but she wasn’t afraid anymore.

I used to keep a mental timeline of “bad things that have happened to me.” From my perspective, it seemed to explain a lot more about who I was than anything else. The line stretched long from my date of birth through every year where I had some kind of traumatic event. Bullied in school, broke my front tooth in half, got both braces and glasses, dated a lot of abusive men, was sexually assaulted, got really depressed and ate a lot of pizza. The details of it are fuzzy now. I just haven’t been keeping track of it like I used to.

More and more, it seems like the past is all a smaller blip on the timeline of my life. In the scheme of things, I’m a baby. Most of my life hasn’t happened to me yet. In the stickiness of New York City in August, I feel less tethered to the past than I have ever felt.