In June, when the anthropomorphic narrative game Goodbye Volcano High was announced, the first thing my nonbinary friend said to me was: “we got nonbinary representation, but not as a human character.” I had a similar concern with Sawyer and Rowan, the nonbinary characters in last year’s Boyfriend Dungeon. They were literally weapons: a scythe and a glaive.

Many video game developers are trying to represent nonbinary characters these days. It’s not easy, and I appreciate that it takes a lot for queer developers to get any of them into a video game. Recently, we’ve seen Bloodhound, who is a masked hunter from Apex Legends, and the masked wanderer FL4K from Borderlands 3.

(My favorite goes further back. I’m a fan of Guillo from 2006’s Baten Kaitos Origins, who is a cloth puppet without a face or a physical body. )

I do wish fewer nonbinary characters in games were exotified, faceless, or non-human. I wish more characters were more like people. I buy birthday cards for my friends, I make omelettes for breakfast, and I coax stray cats into accepting head pats. If you only knew nonbinary people from video games, you wouldn’t think we did any of those things. We are usually portrayed as favored machines for faceless murder, wild and disposable. Thankfully, last year’s Fire Emblem: Three Houses changed that.

The July 2019 Switch strategy exclusive is a Persona-like academy game where the player sends the students off to war. Its lead character, Byleth, managed to subvert my expectations. They were a character that the narrative established beyond a gender binary, and their story felt personally relatable for me.

Fire Emblem is a game in which the player controls soldiers (or “units”) across various battlefields. The series has had player avatar characters since 2003's The Blazing Blade, but they have only been combat units since 2010's New Mystery of the Emblem. Byleth is an oddity among point-of-view characters in the Fire Emblem franchise. In 2012’s Fire Emblem Awakening, the lead character Robin is addressed as “man” or “woman,” depending on which version of the character the player chose. In 2015’s Fire Emblem Fates, the Nohrian crown prince Xander expressed his affection for the avatar character Corrin with “little prince” or “little princess,” again depending on who the player chose to play as.

At the start of Three Houses, there are no such gendered forms of address for Byleth. When the game begins, the player is asked to “select a form,” rather than a gender. Not your form, but a form. The player is asked to select a body for an existing point-of-view character, not an avatar character that is meant to represent the player. As someone who has played dozens of games that asked me to pick a gender, this was a welcome change. I felt that I was picking an aesthetic, and not an identity for the character.

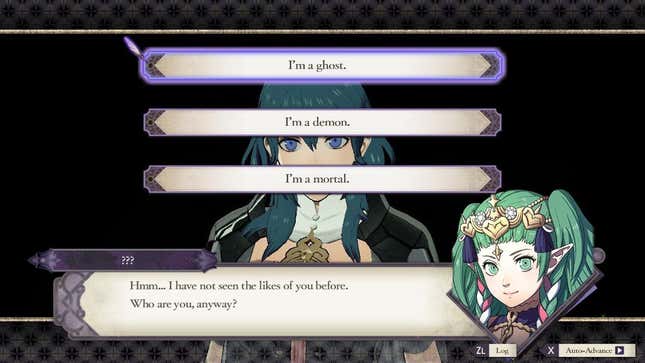

After picking a form, a goddess asks Byleth what they are. She becomes angry if Byleth responds with “demon” or “ghost.” It is impossible for the player to proceed without Byleth affirming that they are a “human.” Many choice-based games will allow the player to proceed, regardless of which dialogue option they picked. Three Houses does not allow the player to advance until they have affirmed Byleth’s humanity. In fact, the wrong choices disappear when they are picked, leaving “I am a mortal” behind. As a game designer, I felt that this was a very intentional design choice. Though I was only picking a host body for Sothis to occupy, the character that I had selected was preemptively declared a human being.

This interaction was meaningful to me, because Byleth was usually dehumanized with titles such as “Ashen Demon” and later “Fell Star.” Even though Sothis relied on Byleth as a pliable host body, just as I relied on them as a point-of-view character, she refused to deny Byleth their humanity. In a way, Sothis was also discouraging me from viewing Byleth solely as a vehicle for my own gameplay experience. This human had their own traumas with being dehumanized by other mercenaries, their own goal of discovering their true identity, and they had their own desire to enact revenge against their father’s killers. As long as they had their own pain and goals, I found it difficult to project a simple binary identity on them.

I’ve seen some people say that Byleth is more of an avatar than a character in their own right. I found this unlikely due to storytelling conventions in visual novels. In most visual novel games, the player is represented by a protagonist who is bland and inoffensive. The protagonist is a typical “everyman” who is able to charm everyone around them with minimal effort. This is because game designers typically want to design a vague protagonist that most players can project on.

Both Fire Emblem Awakening and Fire Emblem Fates had this kind of “everyman” protagonist. In contrast, Byleth’s personality was very difficult for a lot of sociable characters such as Dorothea and Ignatz. They didn’t smile at the right moments, and they didn’t go out of their way to perform emotional labor beyond their duties as an educator. If Byleth was a true avatar, then they would have been universally beloved. They are not. Despite their worldly ignorance, Byleth was clearly socialized normally. They chastise Sylvain for mistreating girls, and they are able to navigate Manuela’s emotional distress. Even so, their father pointed out that Byleth never used to smile before arriving at the academy.

Byleth’s strangeness is a part of their character, and it doesn’t come from the player. As I watched the students tiptoe around Byleth’s strange aura (which varied between each character), I recognized their hesitation in my own friends and family who felt that there was something strange about my gender. For many nonbinary people, our peers realized that our genders were “off” before we did.

Instead of basing Byleth’s gender on the player, Three Houses lends them ambiguity throughout the dialogue. Voiced dialogue is notoriously expensive to produce, so sometimes gender neutrality is used for cost-saving reasons. I don’t think this was the case for Three Houses, which is notable for its minuscule dialogue differences depending on route and student recruitment. For example, Ferdinand will only comment on his coffee during his conversation with Edelgard if he already has a certain relationship level with her retainer Hubert. This conversation appears even more cost-inefficient when one considers that it is only available on one story route out of four. Considering the amount of dialogue customization, it stood out to me when mandatory dialogue about Byleth didn’t have gendered differences. In one route-agnostic scene, Rhea and Seteth refer to Byleth as “dear professor”, “that one,” “child,” and “vessel.” The reasons for their gender-neutrality become apparent when it’s revealed that Byleth is a god-vessel.

Byleth’s gender ambiguity weighed heavily on me as a nonbinary player, since the presence of a gender is so often tied to our humanity. Just as nonbinary people are told that we cannot identify our own gender, the nature of Byleth’s existence was defined by the Church of Seiros. Byleth doesn’t get to be a normal human, because the Church has already canonized them as the next ruler of the continent. At one point, the Archbishop Rhea pontificates about Byleth’s leading role in the continent’s future. They wanted Byleth to rule the world as her mother’s reincarnation. Reading this, I felt numb. At no point did Rhea attempt to inform Byleth about her true plans, or to obtain their full consent. The player knew, but the character did not.

What could Byleth do but agree? What alternatives did they have? Their divinity was innate and immutable. There was more glory in accepting their role as a righteous instrument, rather than living as an awkward human. The story became especially distressing when Rhea objectified Byleth as her own mother. Being forcibly cast into a maternal role is a gendered trauma that many nonbinary people have experienced, and it distressed me.

As the game progresses, Edelgard and the goddess Sothis continue to reject Byleth’s role as a passive vessel. They were right about my Byleth: at no point did they ever agree to be Rhea’s mommy. And in the story branch where Byleth rejects the main church, they didn’t have to be.

What is a nonbinary gender, really? It can be a lot of things. It can be the midpoint between male and female, it can be a combination of multiple genders, or it can be a gender that is completely separate from a male-female binary. It can be one gender today and a different one tomorrow. In Three Houses, it became apparent that Byleth’s gender was their own, with the addition of Sothis’ gender. Sothis is a goddess who lived inside of her host, and she had influenced Byleth’s emotional development. This situation stuck out to me, because spirits are usually portrayed as distinct entities from their host. When Sothis expressed regret at complicating Byleth’s life, I wanted to reassure her that she was not at fault. Her existence was not a burden any more than being nonbinary was a burden.

In order to survive society, people have to perform gender differently depending on the social context. Some people have to be more masculine at work, while they have to emulate feminine traits when navigating family politics. Cis people understand that they are required to wear different guises, but only temporarily. In a cisgender society, contradictory genders appear more threatening when they are an immutable part of a non-binary person’s existence.

Like how Byleth housed a child goddess in their heart, I often thought of my own gender as an inconvenient, yet harmless reality. Other people often felt threatened by this inner ambiguity. Hubert is my favorite character, but he threatens to assassinate Byleth once he infers the second soul living inside of them. He eventually reconciles with them once he finds Byleth harmless. This too, was a familiar experience. I constantly had to prove that my gender was harmless, that it wouldn’t inconvenience the binary people in my life.

In the end, the most compelling part of Byleth’s story is their humanity. They consume multiple meals a day in order to bond with students. They feed cats and dogs within the monastery. They patiently repeat the same lessons with their students to ensure that they would return from the war alive. Byleth’s non-conformity was important to me, because it was never a part of any grand disguise. They were living their best eccentric life.

I think a lot of people misunderstand non-binary genders. They exist even if they are not explicitly called “non-binary.” Byleth’s complicated gender was clear to me. More importantly, I deeply related to the themes present in their story. I don’t think it’s enough for video games to have neutral pronouns: I want stories about being a misfit in a binary world. I want stories about being human in a messy and intolerant world.

It’s not a huge ask.

Sisi Jiang is a game designer who prefers making games over writing about them.