Eliza, a visual novel from development studio Zachtronics, revolves around a therapy service of the same name, powered by machine learning. At one point in the story, an old woman who visits Eliza—mostly to have someone to talk to—unknowingly signs over access to her emails and text messages. As Eliza’s proxy, Evelyn Ishino-Aubrey, I read her text messages and emails, because the game wouldn’t let me not do so. This woman’s situation is much more dire than she let on during her sessions. She’s deeply in debt, estranged from her children, and otherwise utterly alone. Was it OK to access this information? What if I thought doing so would change the world for the better—would that make it OK? Eliza asks a lot of big questions about our relationship to technology. It is less interested in answers.

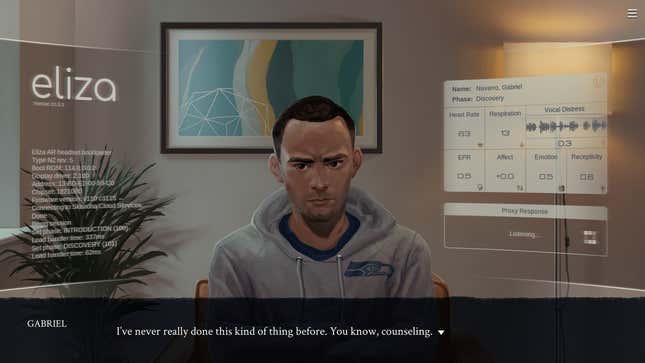

Evelyn, returning to the world after a three-year depression fog, doesn’t feel invested in much of anything that she does. As part of re-entry to society, she has taken a job at Skhanda as a proxy for Eliza, a therapy service that’s powered by machine learning. Secretly, she was also one of its principal engineers, and part of what drives her—as much as Evelyn is driven by things as opposed to wafting into them like a leaf on the wind—is a desire to see how her product is working.

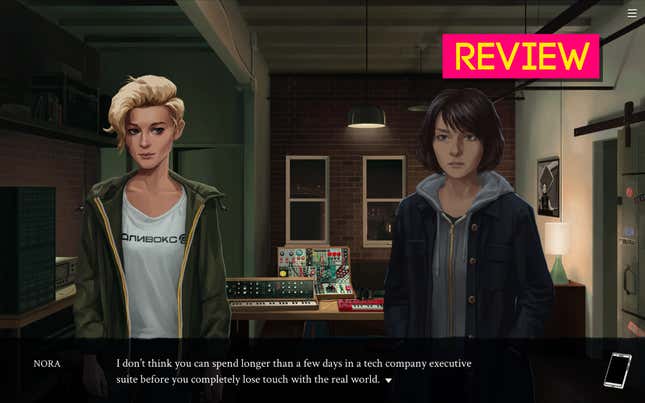

Though gameplay portions are punctuated by seeing clients as a proxy for Eliza, the game is pretty much a bog standard visual novel. There’s a painterly quality to the art and a naturalistic style to its voice acting, where characters stutter and umm and ahh. While you can make dialogue choices for Evelyn, they don’t seem to have immediate effects on the world around you. For the most part, Evelyn doesn’t take strong stances, so interactions with her peers are mostly centered around getting her to feel something.

Eliza is the most fascinating aspect of Eliza, if only for the questions such a service raises. I’ve been in and out of therapy since I was in my early teens, and what Eliza does is familiar. It asks each client how they are, what’s bothering them, and then probes slightly deeper to see why each client thinks they feel that way. Most of the time, it turns the assumptions that the clients make about their situation back on them. It asks you why you think you won’t succeed, why you think that you’re trapped, why you feel anxious when you go out—all good questions for therapists to ask. It appears to help people, or at least gives them a working facsimile of the services of a human therapist. In doing so it collects a huge amount of data that is the sole property of Skhanda.

Through the concerns of young engineer and project leader Erland, the game frequently returns to the questions of whether something like Eliza could help people and the ethics of having all those people’s data and then using it for research or even new commercial ventures, which the slimy Skhanda CEO wants to do. But ultimately, Eliza is the story of Evelyn. I’m just way less interested in Evelyn than Eliza.

We find out early on that Evelyn was driven to her self-imposed hibernation because of the death of a co-worker who was working on Eliza with her. Evelyn’s story of depression and overwork is affecting, but having played a lot of visual novels about being depressed, the story does not add to the ongoing discussion of mental illness in any meaningful way. The realities of Evelyn’s depression are true to life but not given a thoughtful examination. Placing it at the forefront of the story feels like a narrative misstep. Seeing Evelyn become whole is satisfying, but there is no such closure for the ethical questions around Eliza’s creation.

Narratively, Evelyn seems to be absolved from responsibility for helping to create Eliza, although she is repeatedly told she is the only one who really understands it. In my own mental health journey, which has included years of therapy, medication, and a short stint on a text based counseling app, I have also tried to run from the messes that I have made. In most cases, I just made my problems worse. Ascribing fault to one particular actor is in most cases a fool’s errand. In this case, we know explicitly where Eliza comes from: Evelyn’s brain. But she can elide that responsibility. It makes me like her less, and in a world where questions of ethics and big data undergird so many important political and cultural conversations, it makes an otherwise compelling game feel incomplete.

Perhaps there is no fulfilling end to Eliza because the questions it asks have no clear answers. What should companies do with the data they’ve collected? Is it moral for them to own it and use it, even if the people who provided it agreed to do so in their user agreement? It’s hard to take a stance on this when Evelyn doesn’t seem to have a real investment in anything. She’s drifting through her life until the end of the game, where she is forced to make a choice about her future. Will she rejoin Skhanda, even if their goals are ethically dubious? Will she join a former boss in a new venture that pledges to eliminate pain and suffering from the world? Or will she abandon tech entirely, forging a new path? All of these endings tied a bow on Evelyn’s life but left me wanting for a more satisfying conclusion about the future of the Eliza technology.

Evelyn’s first client as an Eliza proxy is so distraught by climate change he has sunk into a deep depression. Eliza makes an effort to say that working on yourself counts as working on the world in the grand scheme of things. In real life, I am inclined to agree. In this game, where Evelyn’s choices can lead to an ending where she uses her massive intellect to fundamentally change how society works, I am not so sure that focusing on her grief is the most useful thing to do. Evelyn has already changed how therapy works in the city of Seattle through her actions. Narratively, she doesn’t ever seem to grapple with or process what she has wrought, and what it might mean for the future. That she doesn’t seem to feel a responsibility to anyone or anything beyond the myopia of her own feelings began to frustrate me. It’s a realistic depiction of depression, but it’s as tiring to play as it is to live.