I awaken in the abandoned Phobos installation, a place both familiar and unfamiliar. The hallways are oppressively dark; everything is so dark. I almost want to reach out and touch the walls to make sure I’m still moving forward. The air is thick with the atonal wails of malfunctioning machinery and the growls of the twice-revived dead.

Hell walks within—within the base, within me.

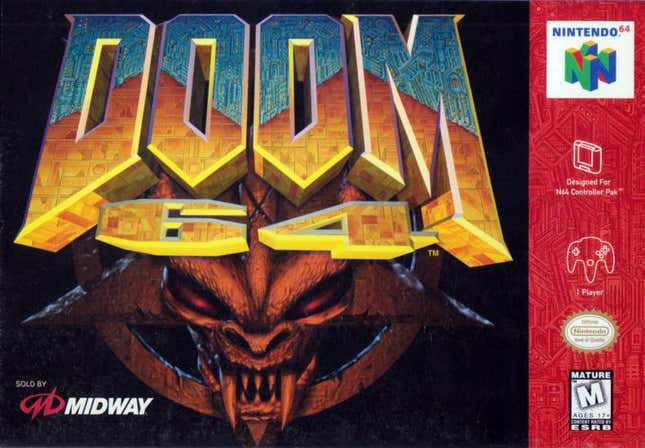

Doom 64 was originally released in 1997 for the Nintendo 64 by Midway. By then, the original Doom was old news in the gaming world, usurped by more modern first-person shooters like id’s own Quake. Doom 64 was no mere port, though, but a new game with completely revamped graphics and an entirely original 32-level campaign. Still, critics largely panned it anyway, and that was pretty much the end of the story until now. Today, alongside the release of the newest entry in the series Doom Eternal, Doom 64 has been upgraded and re-released for the first time on Switch, PlayStation 4, Xbox One, and PC.

In many ways, Bethesda has picked the game least like Eternal to share the spotlight with it.

Doom 64 occupies an uncomfortably liminal space in the history of id’s storied shooter series. It has been largely forgotten until recently, yet it has never quite been obscure. It strikes a pace and tone somewhere between the classic games and the later, survival horror-tinged Doom 3. It shares a near-identical mechanical foundation with its more prominent PC forebears, but marries those rip-and-tear fundamentals with gloomy lighting, wavetable synth, and a genuine sense of sadness and dread.

It’s why I prefer Doom 64 over the more straightforward sensibilities of the originals. Doom and Doom 2 are plenty of fun, too, but 64 is the more relatable, more affective experience for me because it’s an action game that makes room for sadness.

This starts with the protagonist. The Doom Marine was not sketched out in great detail in the original game, but we get a little bit more elaboration on his character with Doom 64. That elaboration is rooted in trauma. Consider this blurb from the original game’s instruction manual (remember those?):

“Your fatigue was enormous, the price for encountering pure evil. Hell was a place no mortal was meant to experience. Stupid military doctors: their tests and treatments were of little help. In the end, what did it matter—it was all classified and sealed. The nightmares continued. Demons, so many Demons; relentless, pouring through.”

The Doom Marine is the archetype of white masculine power fantasy in gaming—a role he continues to fill to this day without much change—so this rare acknowledgement of vulnerability, trauma, and mental illness is important, and one that I appreciate in my own experiences of mental illness. It’s still not often that men in action games are allowed to be tired or sick, and even less often that they’re allowed to be afraid. The result is still a power fantasy, but one tinged with the contours of depression.

It’s not just some nebulous sense of duty, then, that calls the Marine back to Phobos in Doom 64. It’s his own ghosts calling him back, too.

And going back to Phobos—back to Doom, in a way—is uncomfortable and uncanny, a reminder that you can’t go back, really. Despite its macabre imagery, the original Doom is a bright, even campy affair, best played without ever letting up on the run button. But Doom 64 is dilapidated, dark, and deliberately plodding. The marine is supposedly revisiting the same base from the first game, but the layouts are all different. The level design is claustrophobic, subject to unpredictable transformations, and laden with traps. You still move like a night train and carry nearly a dozen weapons, but if you don’t take it a little slower and peek around the dim corners, you’re likely to meet a swift death.

In a lot of ways, Doom 64 is deliberately unapproachable. It actively punishes the kinds of tactics that worked in the earlier games by repopulating cleared sections of the map with fresh enemies or stranding the player on narrow ledges as the floor crumbles into a fiery pit far below.

That unapproachability goes double if you’re playing the original release. Playing a first-person shooter with a single, flimsy Nintendo 64 analog stick is a chore and an accessibility nightmare, but strangely enough, it all adds to Doom 64's mystique. The original cartridge version has a weird quirk where you will only strafe at walking speed unless you specifically map the controller so that you can hold the run and strafe buttons down at the same time. The result is that my reflexes were consistently slower than in the original Doom games, which means I got hit by Cacodemons and Nightmare Imps a lot more often, which means I was a lot more cautious when tiptoeing into each new room.

Things are a little more forgiving in the updated re-release, which I played on Switch. It runs and plays very smoothly, and I never noticed any dropped or torn frames. The default brightness is pretty high, much higher than even the brightest setting on the original version. While I’ve always turned the brightness up to maximum when playing the original just so I can see, I find I have to do precisely the opposite with the re-release in order to preserve the original brooding vibe.

The updated controls are much more responsive and snappy than in the original, to the point where it now feels much more in line with the classics. Curiously, however, I discovered that motion-control aiming is on by default in the Switch version. While this is a helpful augmentation in Breath of the Wild or Skyrim, it’s downright strange in Doom, where you can only move your gun along the X axis. I quickly switched it off.

I think the case can definitely be made that something is lost in the translation. Doom 64 on the Switch in high resolution with modern controls and mid-level saves is a different game from Doom 64 on the Nintendo 64 through a cramped CRT with rougher controls and starting over with a pistol every time you die. You really can’t go home again: the original has aged out of graceful playability and the re-release is inevitably something different, something new. What’s lost in retro authenticity is gained in accessibility, however, and that’s a gain for newcomers and veteran Doomers alike. There’s even a new episode added in to sweeten the deal, and from what I’ve played of it so far, it seems to continue the design language of the original.

No matter how you play it, Doom 64 is a game out of time, already old when it was new. Just how many times have I run through these corridors, hunting for and hunted by evil? By dropping the dad-rock MIDI covers and acknowledging that the Marine is tired and scarred, Doom 64 gets a little meta by asking what is gained by going through the same rip-and-tear motions over and over again.

The developers of Doom 64 originally wanted to call the game The Absolution, but in the end they went with marketability and brand recognition. Even so, they snuck the original title in as the name of the last campaign level, and there were reportedly plans for a further sequel called Doom: Absolution. The word apparently mattered to them.

absolution—/ˌæb.səˈl(j)u.ʃn̩/—noun: forgiveness, especially in a spiritual or theological sense.

Is the Doom marine seeking forgiveness? Redemption? If you follow the lore of the contemporary games, and maybe a few fan theories that propose a working timeline, then perhaps yes, he is.

Am I?

Doom 64, with its depressive atmosphere, hits me in a way the other classic games don’t, despite my love for them. I’ve been living with severe depression for a long time, and it costs and costs and costs. I wonder sometimes if, like the Marine, I’ve willfully trapped myself in a vicious cycle by taking so long to acknowledge my mental illness and the work that goes into accommodating it.

Absolution. I feel the sharp edges of the word, the way in which it cuts to say—the way hard-edged words always do when thoughtlessly brandished or cruelly wielded.

Doom 64 warns against the dangers of drowning in memory until you mis-remember, twisting the corridors you’ve sprinted through a hundred times until you no longer recognize them. It gives you all the tools you’re familiar with from the old games, but punishes you for using them carelessly by dropping you into an inescapable chasm or boxing you in against an onslaught of demons.

For my part, I find comfort in Doom 64’s awkward liminality and resistance to strict categorization as I work through my depression and develop my own queer, nonbinary identity. I find peace in going back to the thing I can’t really go back to and understanding that I’ve grown, and am growing.

I’m working. Working to be more well, but also working to understand and believe that I have value the way I am now, in the way that this weird old game that I’ve always loved and which everyone has the chance to experience anew has value the way it is now. I am working to know that I am enough.

And I am.