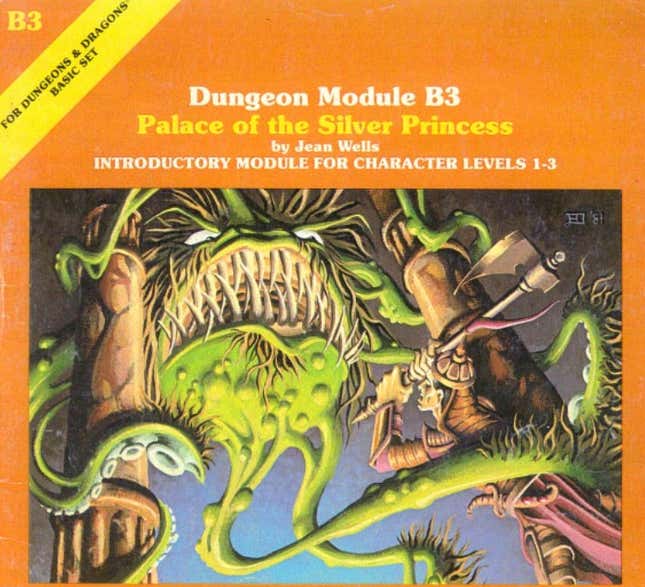

Almost every copy of the first Dungeons & Dragons adventure written by a woman is buried in a landfill in Lake Geneva, Wisconsin.

Those copies, published in 1980, were the masterwork of a game designer named Jean Wells, who worked for D&D’s first publisher, TSR. Wells designed Palace of the Silver Princess to her tastes, and with no regard for TSR’s mandate to make the game more kid-friendly. At one point in the module, players encounter a beautiful young woman hanging from the ceiling, naked, by her own hair. “Nine ugly men can be seen poking their swords lightly into her flesh, all the while taunting her in an unknown language,” the module reads. In-game, this scene turns out to be a simple magical illusion—but the accompanying illustration included in the module that TSR shipped to hobby shops nationally was not.

“A little bit of bondage here, a little torture there, worked its way into the Palace of the Silver Princess module,” Stephen Sullivan, a close friend of Wells and the adventure’s editor, told me. After it was properly reviewed—post-production—TSR’s executives went ballistic. Seventy-two hours after Palace of the Silver Princess was released, it was retracted.

“It was what Jean wanted it to be,” Sullivan said of the module. (Wells passed away in 2012.) “It was her baby. And for another place and another time, it probably would have been just perfect,” Sullivan said. Those retracted modules, now dubbed the “orange versions,” are buried somewhere under Lake Geneva’s flat, Midwestern landscape. It was soon rewritten by D&D designer Tom Moldvay and redistributed with Wells’ name relegated to the second credit.

The countless histories documenting Dungeons & Dragons’ 40-year ascent to the cultural mainstream tend to gloss over the women who made the fantasy role-playing game what it is today. The early D&D heroes we hear about are always big-gutted men with gray beards, who in their basements and at conventions in their name, cultivated the younger men who would carve the game’s legacy in their image. But that’s the lore of D&D, not its story. From the earliest days of D&D, women were shaping its look, its narrative, its affect and its fandom.

This may come as a surprise since, in those nascent years, most women around D&D were tolerant wives and mothers. That’s not because D&D didn’t appeal to women; it had simply inherited the deeply masculine culture of its predecessor—wargaming.

The fantasy role-playing game did not spring out of fashionable fantasy tomes like the Lord of the Rings trilogy, which co-creator Gary Gygax could never pass up an opportunity to trash. Instead, the boot camp dropout was enamored of tabletop wargames like Gettysburg, which promised a “realistic” Civil War battle experience, and the play-by-mail game Diplomacy, a pre-World War alternative history game.

Chainmail was the highly analytical medieval wargame Gygax published in 1971. Its “fantasy” supplement, which he believed would appeal to contemporary fantasy fans, was what gave birth to D&D. The wargaming hobby skewed male to an extreme degree, anecdotal evidence suggests, and in a recent Freedom of Information request for TSR’s FBI file, even the government deemed the average wargamer “overweight and not neat in appearance.”

Arguing over minute details of infantries, historically-accurate musket use, or what square footage was represented by a movement counter was not, apparently, a popular free-time pursuit for women of the 1970s. And several women who did play D&D in the late ‘70s and early ‘80s struggled against the very male-centric culture it had absorbed.

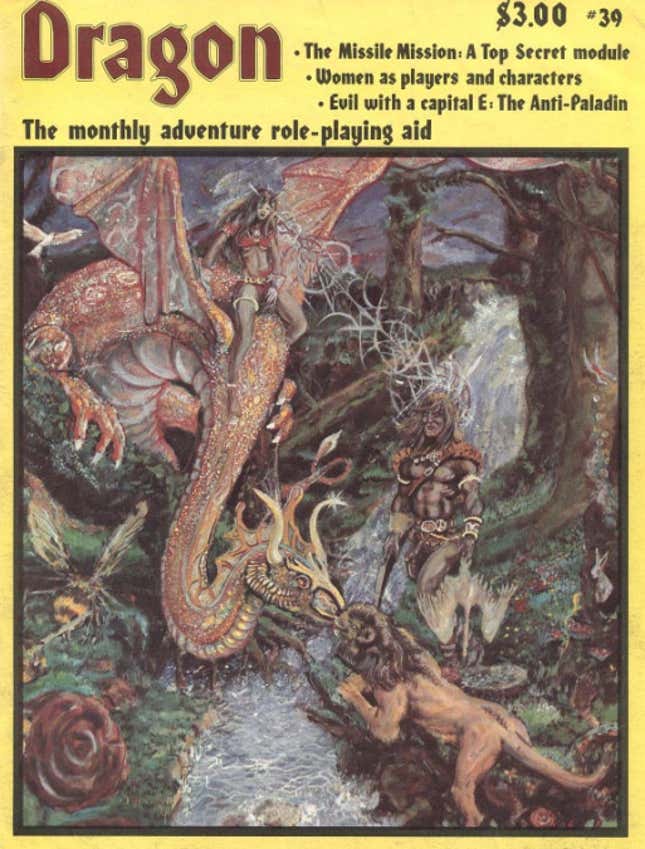

In the July 1980 issue of Dragon magazine, TSR’s official D&D publication, Jean Wells and her colleague Kim Mohan penned the editorial, “Women Want Equality. And Why Not?” Women from across the country had written in about the “unfair and degrading treatment of women players,” who comprised, they wrote, about 10 percent of D&D’s fanbase. One reader recalled how her adventuring party forced her to seduce a small band of dwarves so her party could kill them. Another told of how her Dungeon Master made her Cleric fall from her god’s graces when she became pregnant.

Wells and Mohan interpreted the appearance of the game’s female miniatures—slave girls in chains, “female magic-users wearing nothing but a smile and a bit of cloth draped over one arm”—as warning signals to potential female adventurers. In fact, the cover of that very Dragon issue advertises a long-legged woman slumped over a dragon, her crop top not covering the bottom of her breasts and her hand placed seductively between her legs, from which a dragon’s long neck extends.

Part of why this flew was because, in its very ruleset, D&D assumed a mostly-male audience. In the mid-70s, that ruleset faced accusations of chauvinism when it became clear that women characters’ strength was capped four points lower than men’s. It compensated with the “Beauty” attribute, a substitute for “Charisma.” D&D also featured a “Harlot Table,” a bounty of twelve “brazen strumpets or haughty courtesans” players could summon with the roll of a die.

“Female players of D&D, AD&D and other role-playing games are finding it necessary to cope with discrimination and prejudice as they seek the satisfaction and fulfillment they are entitled to receive from playing a role in an adventure game,” Wells and Mohan wrote.

Penny Williams wasn’t into “large stacks of paper counters.” It wasn’t that the stats, tables, and game pieces of a typical wargame intimidated her—after all, she was a chemist. She just found it all to be boring. Back in college in the ‘70s, Williams watched a couple of her friends’ D&D sessions and, inspired by the game’s endless possibilities for communal storytelling, bought herself a copy of Dungeons & Dragons at her local hobby shop. She quickly became the group’s Dungeon Master of choice.

TSR hired Williams right out of college as a “game questions expert,” tasking her with answering the bags and bags of mail fans sent in. Later, she began publishing her answers in Dragon and, eventually, coordinated the RPGA network, which hosted D&D tournaments and events nationally.

“At Gen Con Origins, people needed somebody to DM one of the sessions for the AD&D [Advanced Dungeons & Dragons] Open,” she said over the phone earlier this year. “So, I grabbed my stuff and met the team and did that. One of the semi-washed teenaged boys on the squad there looked at me, gaping, and said, ‘It’s a woman!’. I said, ‘10 points for perception.’”

Wells was the first woman designer hired by TSR. An avid D&D player since a college canoe trip in the Ozarks, Wells had come across an employment ad for a designer in an issue of Dragon in 1978. She wrote to Gygax, who, after some correspondence, offered her a job at TSR in Lake Geneva. “He was hiring my imagination and would teach me the rest. I also suspect, but am not positive, that being a girl had a lot to do with it as well,” Wells later said in an interview.

Wells was a proud Southerner whose fried chicken endeared her to colleagues, and at TSR, her strong-willed personality had her doing everything: She edited, she illustrated, she wrote, she managed. She was an assertive woman whose loyalty was precious. And when things weren’t going her way, she was known to pull the “Gygax” card.

Years after she’d gotten the job off an ad in Dragon, Wells became the titular “Sage” for the magazine’s “Sage Advice” column. She used the column to exercise her ferocious, sometimes cutting, wit. The strangest and most off-base questions were most likely to garner Wells’ “advice.” In one column, a player wrote in, “How much damage do bows do?” Wells responded, “Answer: None. Bows do not do damage, arrows do. However, if you hit someone with a bow, I’d say it would probably do 1-4 points of damage and thereafter render the bow completely useless for firing arrows.”

“I adopted this approach because this is who I am,” Wells said of the column in 2010. “I felt the youngsters under the age of sixteen were spending far too much time being far too serious about a game when they needed to focus some of that attention back on their families and schools. I’d hoped the kids would see the humor in the situation and not take the game so seriously that every breath they took, every word they said was about D&D.”

On TSR’s third floor throughout the late ‘70s and early ‘80s, Wells or Williams would happily hop into one or another of their colleagues’ constant stream of D&D games. They frequently wrote their own adventures for friends and co-workers, too. There, in the office, the line between playing and playtesting blurred as D&D’s boisterous designers-slash-fans weighed stats, balanced tables and mapped dungeons.

Several of their female colleagues were less enthusiastic. Despite D&D’s constant presence in the office, playing the game held no interest for many of TSR’s early female employees. In interviews, some said they didn’t feel comfortable rolling up characters or slashing their way through dungeons with their coworkers.

Rose Estes, whom TSR hired in 1977, says D&D’s culture, or at least its manifestation on TSR’s third floor, did not appeal to her. For years, Estes was a one-woman crisis management team when God-fearing families across America caught wind of D&D’s alleged Satanic underpinnings. In interviews with newspapers, she explained how D&D was not responsible for the infamous missing D&D-playing college student who was believed dead in his campus steam tunnels. She wrote explanations of how to play, which she’d talk about on national radio. A diehard fantasy fan, Estes’s three children were all named after Lord of the Rings characters. Despite all that, her more gregarious colleagues repelled her from the game. The raucous disputes over stat tables and spell effects and the blistering arguments over what modifier applied to which action really turned her off, she said.

“I never did actually play the game,” she told me. “Also, I had three kids. So there wasn’t a lot of time to spend playing games.”

Darlene (whose name is just that), a freelance artist and cartographer for TSR, described that same environment as “hostile.” Fighting over rules was not her idea of fun. “It all developed out of cowboys and Indians,” she said via phone. “Pew, I shot you! No you didn’t, it just grazed me! No, I did! Okay, we’re gonna figure out if you shot me or not. Get dice.’” If women attended the after-hours games at the office, she said, they’d be designers’ wives or girlfriends, either dropping them off or picking them up. If they stayed, they’d stay and knit—with the tacit understanding that they didn’t quite trust their partners to be there alone.

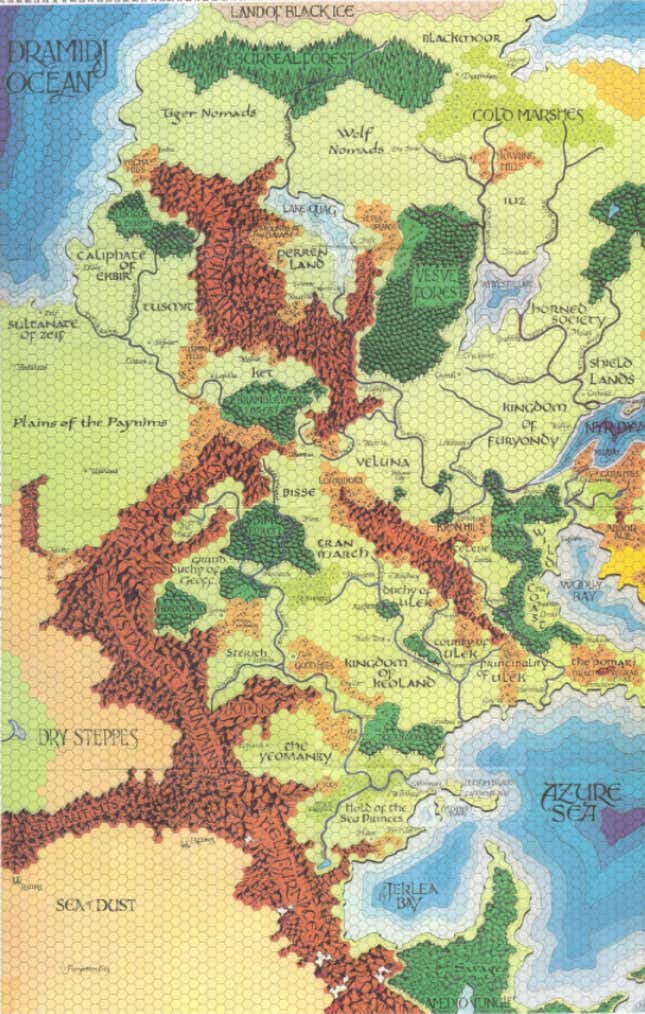

Darlene is credited with creating the telltale visual style of TSR’s print publications. After college, where she studied calligraphy and art, Darlene was working at a small graphics concern in Lake Geneva when D&D designer Mike Carr walked in. He commissioned a flyer for D&D convention Gen Con, then later slyly asked her on a date. Not long after, Carr’s colleague at TSR showed her illustrations (a fat unicorn, a mermaid) to Gygax. Darlene was brought on as a freelance artist and those illustrations eventually ended up in the Dungeon Master’s Guide. (She had studied calligraphy in London from Queen Elizabeth’s scribe, so she was more than qualified to illustrate Dragon’s headers, with their scrolls or art nouveau-style flourishes.)

The map for Gygax’s campaign setting, Greyhawk, was Darlene’s most iconic accomplishment for TSR. It’s a map, she recalls, that Gygax deemed “born perfect.” In her small apartment, Darlene rolled out a huge scroll of paper, on which she penciled in, and then confidently penned, a two-sided map’s mountains, hills and towns. “I almost had to lay on the drafting table to do it,” she laughed. Getting more serious, she explained: “I reached deep inside myself and got in touch with this Medieval monk. I was just sort of following his instruction when I was doing that map.”

And yet, in her six years freelancing for TSR, Darlene was never hired full-time.

She hadn’t considered her gender as a reason why until years after she quit freelancing in 1984. “I knew they wanted artists, and I was told not to apply,” she told me, “that my application would not be considered. I didn’t understand why. They said, ‘Because you don’t play the game.’ And I went, ‘Oh.’” Years later, she was told that the person in charge of hiring her did not want to hire women, which former editor Stephen Sullivan also confirmed to be true.

“If I were savvy, I’d have said, ‘Well, all right, when I do play the game, can I reapply?’ I just took him at his word.”

Women were the champions of TSR’s books department, a much-celebrated division that published novels inspired by D&D’s dragon-slaying, court intrigue and daredevil dungeon-crawling adventures. Alice Norton, under the pen name Andre Norton, wrote perhaps the first novel set in a D&D universe: Quag Keep. She figured that a male name would endear her to fantasy fans. Rose Estes, who had been a “hippie, a student, a newspaper reporter and an advertising copy writer,” later struggled to help TSR’s growing books department catch D&D’s winds.

Estes was TSR’s 13th employee, through the ‘70s and ‘80s, she did everything from answering phones to publishing New York Times best-sellers. One summer, Rose took a brief break from TSR to write some articles about a traveling circus. She followed the caravan to Decorah, Iowa, where, one day at a laundromat, she noticed a shelf of books. The one she picked up happened to be a choose-your-own-adventure novel. “I realized within a few pages, it was exactly what TSR needed to do to make people understand D&D,” Estes said.

Pushing aside her traveling circus adventure, Estes and her children drove back to Lake Geneva, Wisconsin and dropped the book on the desk of the head of sales. He gave it, and her, no thought for weeks, she said. She continued to remind him about the book, and he continued to ignore her, until finally, she remembers, he told her to write it herself if she cared so much. “I’d never written fiction. But I was so mad—Don’t tell me I can’t do something—so I did it. I wrote the book, longhand on legal pads. I took it back and gave it to him.” Later, after a meeting with a publishing company, Estes’ choose-your-own-adventure book was allegedly touted as an upcoming product. “The [head of sales] came back and casually dropped a pile of legal pads on my desk. He said, ‘Write three more.’ So I did.” Estes went on to write TSR’s best-selling Endless Quest books, like Mountain of Mirrors and Revolt of the Dwarves.

In the late ‘70s, a mutual friend introduced Estes to Jean Black, who had published a 14-volume aviation and space encyclopedia in London before moving to Lake Geneva with her husband. She had heard of D&D, but didn’t know it was published in Wisconsin. In no time, Black was brought on as TSR’s managing editor of its books department. And in 1985, Black would choose TSR writer and current New York Times best-selling novelist Margaret Weis to pen the Dragonlance Chronicles, based on popular D&D adventures. They are still in print.

Thanks to the women who helped pave her way, Weis says her years in TSR’s books department “were some of the best of my life. We just had a wonderful time.”

Last year at Gen Con, Weis gave a talk about the accomplishments of women who influenced D&D in its nascent years. This year, Weis will be Gen Con’s 50th Industry Insider Guest of Honor. Once the gates were flung open, more and more women like her were able to share their fantasies with the world.

Gary Gygax will always be the face of D&D. That will never change. But today’s version of D&D’s Player’s Handbook credits women as contributors more than any previous edition—about a quarter are female, compared to a fifth in the last version and about a tenth in the one before (Seventy-five percent of D&D’s branding and marketing team is female). Under Wizards of the Coast, which bought TSR, D&D has embraced equal-opportunity escapism, showcasing its “Human” race with a woman of color. More importantly, that escapism is seeing more women at its helm.

Slowly, recognition will come to the Darlenes and the Weises who were there, helping to launch this big, weird thing into the greater mainstream world. Yes, it’s true that the game’s history and ruleset were at the beginning less welcoming to women; but confusing and deepening the too-smooth narrative of a game whose culture evolved from chauvinism to liberalism are the women who carved out a space for D&D, from the start, expanding its reach and relevance to this American mainstream—and whose legacies, like The Palace of the Silver Princess’s, have for the most part been paved over.