I am scared of many things in video games. Sharks mostly, but there’s other stuff. Nothing has ever scared me, though, as much as 1992's Alone in the Dark.

Infogrames’ classic is one of the most important horror games ever made. Everything from Silent Hill to Resident Evil owes a debt of gratitude to Alone in the Dark. Its mix of polygonal characters with static backgrounds was fairly common for the time, but using it for a horror game was something new and terrifying. For most games, restricting the camera while allowing for 3D movement was simply a visual fad of the time, but for Alone in the Dark it let the horror take on a cinematic quality, with every room designed and portrayed with an eye to scaring the crap out of you.

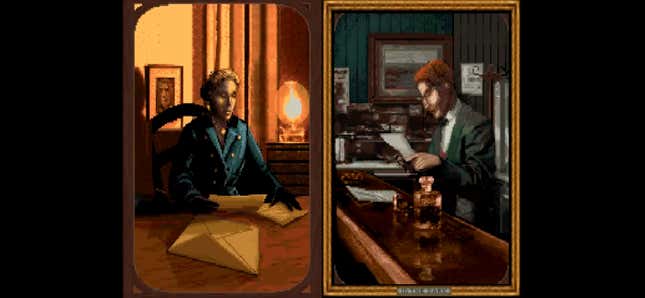

This leveraging of technological limitations extended to your character’s animation. The game’s playable characters—Edward Carnaby and Emily Hartwood—are portrayed in about as limited and 1992 a way as possible, all dangly limbs, jagged faces and shambling walks.

Yet their slow, deliberate pace helps add tension to the game that a faster and more fluid character would skip. And it helps the bad guys too; the zombies and monsters you fight in this game are lumbering, hideous creatures, whose polygonal frames look far scarier in the abstract than if they’d been fleshed out.

Also notable was Alone in the Dark’s art design. When we think of horror games, we tend to think in horror cliches like ruins, rain and darkness. Resident Evil 7, basically.

But Alone in the Dark was having none of that. Its first steps may have you expecting convention, as you walk down the driveway towards a clearly haunted and abandoned old mansion, but as soon as you step inside you notice two things. This game is lit up, and this game is colourful.

Alone in the Dark’s colour palette is maybe the most defining thing about the game. Where almost every other horror game in existence has been content to work with blacks, greys and a splattering of red, AitD’s levels are awash with greens, burgundy, pinks and blues. It’s beautiful, in a way that interior design historians and 90s PC gamers are best equipped to appreciate.

Yet for me, it’s also the source of the game’s greatest horror.

There’s a great passage in the Half-Life 2 art book where Ken Birdwell recounts the hiring of artist Ted Blackman, who had just shown Gabe Newell an illustration in his portfolio of a dog monster with a huge dick. “Well, I was thinking, what’s scary to our target audience?” Birdwell remembers Blackman saying. “A lot of them are 14 year-old boys, they’ve seen all the big brutish monsters with guns for hands already—that won’t really do it—so I’m thinking what fears do they really have? So I decided to go with something that elicits a homophobic response.”

Real horror isn’t stereotypes. It’s magnifying your existing fears and throwing them back in your face. I hate sharks because they’re representative of the deep unknown beneath the waves (I nearly drowned in the ocean when I was 15), and I was terrified of Alone in the Dark because it reminded me of...my aunt’s house.

When I was a kid, I’d sometimes drive with my folks for a few hours and stay with my aunt for the weekend, who lived in this old farmhouse on an orchard in the middle of nowhere. It was a nice house, and I had a lot of fun there during the daylight hours, but at night that place would scare the shit out of me.

I was born and raised in the city, so the fact we were staying on a single house on top of a big hill kinda freaked me out. Looking out the windows and seeing...nothing sounds downright tranquil to my adult self, but as a kid, I found the solitude and darkness unsettling.

The scariest thing was the wind. Being on top of a hill, at night the wind could really get howling, and because the place was surrounded by trees, there was this constant noise as the branches swayed and smacked up against the windows of the house.

I have this defining memory of having to go to the bathroom one night, when I was probably around 6-7, and leaving the light and warmth of the living room to head down the hall. It was pitch black, and all I can remember is freezing in place halfway down the corridor, as branches rattled against glass, my concentration weirdly fixated on how old the house was, with its burgundy walls, green roof and intricate black and white tiled floor.

Fast forward to 1992 and...oh.

Oh no.

Great. Here I was, trying to enjoy this revolutionary new video game, and I’d ended up trapped inside a childhood nightmare. Only now it also had zombies in it.

For all of Alone in the Dark’s efforts to scare people through animation, sound and level design, the biggest impact it had on my heart rate had simply been the accident of making its haunted mansion look like my aunt’s house. Great job, video games.

If you’ve never played the game, it’s available on PC marketplaces (and app stores if you’re desperate). And while it may seem creaky by modern standards, that’s half the point, and aside from the art design I think the game’s open world, non-linear design has aged really well.

READ MORE:

Murder House Is Everything Terrifying About Low-Poly Horror