Sean Baptiste, like a great many people, often turns to humor as a means to cope. Learning that a sample of his cerebrospinal fluid featured traces of P. acnes (or propionibacterium acnes) was no different. He joked to his doctor, 'Oh, I'm going to have brain zits?' The doctor didn't think it was too funny.

INSPIRATION OUT OF TRAGEDY

In a roundabout way, the brain tumor that very nearly ended Baptiste's career in video games in 2010 also led him to pursue that career in the first place when he was first diagnosed around 2003.

"I couldn't work, I couldn't do anything. So I spent a lot of time just up in my room, playing video games. And I started thinking, 'When this is over…' – cos that's how I kept approaching it – 'When this is over, I'm going to do something that I love. I'm going to get into video games.'"

A 2003 PlayStation 2 game by the name of Amplitude became Baptiste's particular obsession during the lead-up to his surgery. It wasn't long before he learned that its developer, Harmonix, was based in Cambridge, Massachusetts, less than an hour south of Amesbury MA, where he made his home at the time.

Baptiste was so confident that his upcoming surgery would run smoothly that he began to apply, constantly, perhaps overzealously, to QA jobs at Harmonix. Rejection after rejection failed to temper his determination. Not even an email from then Chief Operating Officer at Harmonix, Mike Dornbrook, to the effect of, 'This is probably never gonna happen. We're not actually looking for help,' was enough to convince Baptiste to throw in the towel.

"It was pretty much the only place I wanted to work, too, and I was, like, 'No, I'm not accepting that. I'm going to keep doing it, and you're eventually going to need somebody like me.'

One day, following all of the misfortune surrounding his health, Baptiste caught a rare, lucky break. A friend of a friend landed a QA role at Harmonix, and it wasn't long before he went in to bat for Baptiste from the inside. "He was, like, 'You should hire this guy,' and they're, like, 'That crazy person who just keeps writing?' 'Yeah, yeah, yeah. He'll do fine.'"

But in the years before Baptiste eventually joined Harmonix's QA department, he was forced to confront the reality of his condition and come to terms with it all. Without health insurance of any kind in the early 2000s, Baptiste had to fight bureaucracy for a long, frustrating period to secure the Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) that confirmed his tumor. After this, another year-and-a-half struggle ensued to secure the insurance necessary to fund his first surgical operation.

"The tumor I have, it blocks cerebrospinal fluid from getting back out of my head. Basically, the sac in the middle of your brain that holds all of the cerebrospinal fluid just gets bigger and bigger and bigger. In a lot of ways, it's like being concussed but, like, all of the time; a lot of pain directly behind your eyeballs, cos it's literally pushing against your eyeballs."

Surgeons drilled a hole into Baptiste's skull on March 15 2004, where they then installed a shunt that acted, he describes, as a straw into his brain. A pump that runs on barometric pressure siphons the excess cerebrospinal fluid from his brain through a tube that runs down his chest, redeploying it into his abdominal cavity. He still requires and wears this contraption to this day.

"LIKE LIVING A DREAM"

Thanks to perseverance and that friend of a friend on the inside, Baptiste's entry into the game industry was a brief QA role for Harmonix's Karaoke Revolution 3 in which he "sang for money all day." Because he joined late in the process, the gig lasted only a month and a half. "So I basically got my start in the industry, and I was immediately laid off," he laughs. "I had moved out of my house. I had moved down here for that month-and-a-half of a job knowing full well that this was what I was going to do, and it didn't matter that this was a contract job; I was here to stay."

Thankfully, he found another role shortly afterwards at Stainless Steel Studios: a Cambridge, Massachusetts-based dev that specialized in real-time strategy games (such as Empire Earth and Rise and Fall: Civilizations at War).

"I loved the people I worked with directly, but it was a very weird company to work for," he begins before becoming particularly animated, waving his arms playfully. "Especially for somebody who had come from Harmonix where everybody's cool and there's women who work there too and things are great and this is really fun! And then to go to, like, a very old-school game company was very uncomfortable for me. So at the first moment that Harmonix would have me back, I ran back."

Baptiste became the QA lead on the GameCube version of Karaoke Revolution Party. Because this iteration supported a dance mat, he was now singing and dancing all day for money. He soon realized that he did not want QA to be the endpoint of his career in the video-game industry, and he eventually managed to land a technical artist position on Guitar Hero II despite lacking "any marketable technical skills or any real art skills." He describes his take on this role as being something of a translator or mediator between the art team and the code team.

With the runaway success of the Guitar Hero franchise, things began to really heat up for Harmonix. After the company's sale to Viacom in September of 2006 and fulfilling its contractual obligations with Guitar Hero, Harmonix focused its efforts on what would become the Rock Band phenomenon. "It seemed like we were going to be self-publishing in some way, and that was going to be a community, and there would have to be someone to manage that community. So I just sort of raised my hand, because that seemed pretty fun."

From badgering Harmonix repeatedly and unsuccessfully for a QA role, Baptiste now held the community development manager position for what would become the studio's most successful property. It was a gig that would see him constantly on the road through the release of four games in the series. "[Former director of publishing and PR at Harmonix] John Drake and I flew everywhere and just did everything all of the time and basically never came home," he relates. "Which was kind of exhausting, and I got to meet lots of cool people and got to be on the red carpet at music-award shows and go to the Grammys. It was crazy. It was like living a dream."

"ROLLING ONES"

It wasn't long before the launch of The Beatles: Rock Band when the headaches returned. "Like, really bad headaches again. And I kinda felt something was wrong."

The shunt installed in Baptiste's brain had become skewed in a manner where it drained too much cerebrospinal fluid from one side of his brain and not enough from the other. The procedure to correct this was straightforward, and Baptiste "recovered pretty fast, actually." But it was shortly after Christmas that year when the traces of P. acnes were discovered in his cerebrospinal-fluid sample taken during the corrective surgery. "We get a call from my doctor that I need to come in immediately," he explains.

"Over the period of the next six months – from that first surgery to the last surgery I had – I had roughly 12 operations on or inside my brain," begins Baptiste. "The way I put it was I just kept rolling ones. Like, it was just critical failure after critical failure – just the worst luck lined up in a row."

For Baptiste, leaving Harmonix to focus on his recovery was devastating. In many ways, his work was his life, and in the blink of an eye, he went "from going to the Grammys and being on the red carpet and everything to, a couple of days later, drooling on myself and can't remember my own name."

But being forced to leave his dream job was far from the worst thing to result from this turn of events. "The thing is, once you have that much traumatic stuff done to your brain, bad stuff starts happening."

SIDE EFFECTS

Sean Baptiste has a superpower of sorts. "You know how somebody with a bad knee, they know when a storm's coming?" he inquires. "Well, I have that, but it's my entire brain. So when we get bad weather, when the barometric pressure drops, I can feel it a few hours ahead of time. Upside: I'm a great weather man. Downside: the pain. It's like Wolverine with the claws. 'Does it hurt?' 'Every time.'"

The tumor still exists in Baptiste's brain and, unfortunately, there's simply no way to get to the tumor and extract it. He still requires the cerebrospinal fluid-draining shunt to this day. He still encounters side effects to varying degrees, but his condition has improved immensely from when he was at his lowest point.

"I lost my memory. A lot of times, I couldn't really even remember my own name, which still occasionally happens," he explains. A human being's short-term memory can generally process seven thoughts simultaneously. At its worst, Sean's memory maxed out at around four. "So I was kinda like a goldfish, for all intents and purposes."

"One of the worst things was I ended up getting this thing called dissociative sleep, which was I would fall asleep, except my eyes would be open and I would be standing there," he continues. "Basically like sleepwalking, except you could interact with me, and you could ask me a question and I would answer it. My answer would almost never make sense. It's kinda funny, but it's also very scary, and it was very scary for my wife, who had to deal with this person she didn't even know anymore."

Baptiste recounts a particular incident where his wife, Maria O'Brien, returned from work at Harmonix to find him walking back and forth in a line, a rum-and-Coke in each hand, and their dogs following along behind him. "Hi! You're home! We're having a parade!" he informed her. "I made these for you!"

"I'm trying to hand her these drinks, and she realizes that I've fallen into dissociative sleep. So she tries to get me to sit down in the living room." Maria leaves his side momentarily to change from her work clothes, but soon hears a commotion in the kitchen. She rushes in only to find Baptiste with his head in the refrigerator vegetable drawer. "I'm talking to the vegetables. They're telling me things about stuff."

"And the thing is, I think, for her, she's, like, 'Is this something that's dangerous? Is he going to be in a dream where something goes violent for him or something like that?' It's impossible to know how I'm going to handle things. And that situation was very scary for her, and it was very scary for me, too, knowing I had no control over it."

LAUGHTER: MEDICINE AND THERAPY

Baptiste used his love of comedy as a coping mechanism, but he also learned to harness it as a large part of his cognitive therapy and recovery. "My wife was really pushing me for this," he begins. "Maybe developing a different type of therapy for myself and kinda coming up with my own while working with my cognitive therapists and my psychiatrist and everything." He decided that it might be helpful to revisit the jobs he always wanted as a child, and top of that list was 'stand-up comedian.' Naturally, this would present a significant challenge for someone with severe memory problems, but Baptiste and O'Brien hoped that it might prove to be a helpful one.

"So we decided also that we were gonna film this and maybe try to sell it as a pilot for a TV show, which was going to be called 'When I Grow Up,'" says Baptiste. "And each episode was going to be me trying to do a different job that I wanted to do as a kid as a way of dealing with brain injuries. The pilot is all stand-up comedy." He attended ImprovBoston in Cambridge – a nonprofit improvisation theater – to receive stand-up lessons from friend and revered local comedian Dana Jay Bein.

"My first performance, I don't remember," relates Baptiste. "I had to have the filmmakers send me footage so that I would know that I was even there in the first place." He followed up his debut performance with a full show at ImprovBoston a month later, and then he became a relatively active member of the local comedy scene. He informs me that his first routine was written around the aforementioned traumatic dissociative-sleep incident he and his wife experienced.

"Finding a way to make a joke about a horrible situation is my way of taking control of the situation and giving myself power over it," says Baptiste. "Actually doing the stand-up comedy and actually forcing myself to do that really helped. During that time, I was able to try and get my strength up enough to propose to [Maria]."

MAKING A GAME FOR COMEDIANS

Once Baptiste had recovered enough, he yearned to return to work. Around two years after his health issues forced him to leave, he returned to Harmonix as an intern, "just doing some busy work, helping to fold T-shirts and stuff." But Harmonix had, naturally and understandably, moved on somewhat over the course of Baptiste's absence, and in many ways, so had he.

"I had been playing, while I was recovering, lots of indie games, and there is something very attractive about that," he begins. While Baptiste fostered a sincere love for the Rock Band franchise, he felt very little ownership and influence over its identity. The prospect of working at an indie studio presented an opportunity for him to leave his stamp on games in an entirely new way.

"We had a new game, and we felt that we were weak on the marketing and press side," says Eitan Glinert, founder and president of Cambridge MA's Fire Hose Games. It wasn't long into their first interview before Glinert was sold on Baptiste as an ideal fit for his studio. However, after an open and frank discussion about Baptiste's condition, there were question marks over how it might affect his ability to perform, and whether the work might push him too far. "And we decided, 'OK, we'll give you a 20-hour-a-week thing. And you need to let me know instantly if anything happens. And furthermore, if at any point you have a headache or you're not feeling good, like, you're not allowed to be here."

Baptiste started work at Fire Hose, part-time with full benefits, in July 2012. After around three months, he bumped up to around 30 hours a week before eventually coming on full-time. His first major project was coordinating PR for Go Home Dinosaurs! – a tower-defense game that released on Steam and iPad. But it also presented Baptiste with his first opportunity for creative involvement in a game; he wrote the game's spoken dialogue, and he directed all and even performed some of the game's voiceover work. "And I was, like, 'Hey, you know what? I kinda like this side of game development. I should do more of that.'"

After shipping Go Home Dinosaurs!, Baptiste pitched his first ever game to Glinert. "I wanted to make a game for stand-up comedians, and I wanted to make a game for the people who helped me," he contends. "I wanted to make a game that made people feel more clever. I wanted something that celebrates Oscar Wilde and Dorothy Parker. I wanted to make something like that; something that was funny, that applauded not humor but wit and cleverness."

Let's Quip is a debating game born of a conflict-diffusion tactic Baptiste employed during his Harmonix days. He'd ask workmates engaged in circular arguments to draw a word from a Rock Band cap and then give them around 30 seconds to state their case as to why their respective word was better than their opponent's. Once the rest of the team had voted and a victor had been declared, Baptiste observed that those involved in the initial argument would quickly move past it.

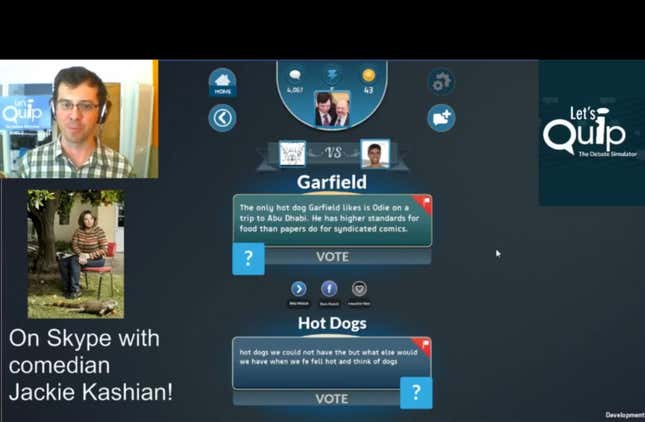

The digital incarnation, currently in beta on Facebook and with mobile versions around the corner, takes this core concept and limits each player's argument to 140 characters. The idea is to outwit your opponent, the arguments voted on by other players in something of a non-monetized energy mechanic; once players vote on enough matches, they earn the opportunity to play another round.

A two-person team, Baptiste and programmer/co-creator Sharat Bhat promote Let's Quip with a daily livestream on Twitch, where they invite comedy personalities along to chat, crack wise and vote on matches. Recent guests have included national touring comedian Jackie Kashian and graphic novelist and comedian Keith Gleason. "I never told him to do that," Glinert says of Baptiste's Twitch initiative. "He came up with this on his own, and he did it back before Twitch was a thing. Like, he just found this thing that he thought was cool, he got it set up, and that's been a huge deal for us."

HEAD DOWN, CHARGE FORWARD

Vast swathes of Baptiste's life have been erased from his memory as a byproduct of the trauma associated with his many brain surgeries. As such, he relies heavily on reconstituted memories from those who were around him at the time in order to piece together key moments from his life. He describes his memories as essentially being "Polaroids of someone else's life."

"For my birthday two years ago, I asked that everybody, all my Facebook friends, instead of sending me a present of a card or whatever, that they just share a story that happened between us, no matter how banal or boring, so that I can recreate some of those memories of things that happened."

Before we part ways, I ask Baptiste if there's anything in particular that he's learned from this whole experience. "Probably, but I keep forgetting it," he responds dryly before chuckling through a sharp apology. "Everything is going to go wrong and everything is going to get worse, and you're going to have parts of your life where bad things just keep on happening and keep on happening and there is no end to it. And the best thing you can do when that happens is just… keep your head down and charge forward."

'This is gonna sound terribly depressing, but I don't mean it that way: when you've gone through something like this, you accept that you're already dead in a way, but you still have some time before they check the card. Having that lack of fear is actually very freeing and has allowed me to be less afraid of just doing the shit that I need to do for me. I'm not afraid of failing anymore, because who cares? That's not necessarily an attitude I had before, and it's weird to say it, but I think I am kinda grateful for it now."

Chris Leggett is a freelance journalist based in Seattle.

Illustration by Jim Cooke.