Yesterday’s announcement of Microsoft’s plan to purchase Activision Blizzard King for nearly $70 billion immediately sparked discussions about antitrust laws and monopolies, financial terms that pop up whenever a high-profile company purchases another high-profile company. While the merging of Microsoft and Activision feels like far too much power being consolidated under one roof, once you understand what a monopoly is, it’s pretty clear this isn’t it.

In economics a monopoly occurs when a single entity, be it a person, company, or government, establishes complete control over the supply of a product or service. In order for you to have a monopoly on pies, for example, you would have to be the only person in the market creating and selling pies. Perhaps other potential pie makers don’t have access to ingredients. Or maybe no one else in the market wants to make pies, leaving you as the only game in town. In this hypothetical situation, you are the master of pies. As the master of pies, you have the ability to set the market price. If no one else can or is willing to challenge you in the marketplace, you can charge whatever you want, or as much as your customers are willing to pay. That’s the simple, economical definition of a monopoly.

The legal definition of a monopoly is a bit more broad. In order to attract the negative attention of an organization like the Federal Trade Commission (FTC), a company doesn’t need to completely dominate a market to the exclusion of all competition. It just needs to possess significant market power. We’re not talking about brand recognition or having a large stable of well-known AAA video game franchises here. We’re talking about having enough power (and little enough competition) that a company can set inordinately high prices for its products.

No matter which version of a monopoly we’re talking about, economic or legal, the lack of competition is a key characteristic and concern. Healthy competition makes for a healthy marketplace. If someone else is selling the same thing you are selling, you are motivated to find ways to make the thing you are selling better than theirs. That’s how innovation happens. If you’re the only one making, say, an annual NFL-licensed football video game, there’s more of a chance this year’s version will just be last year’s version with a fresh coat of paint.

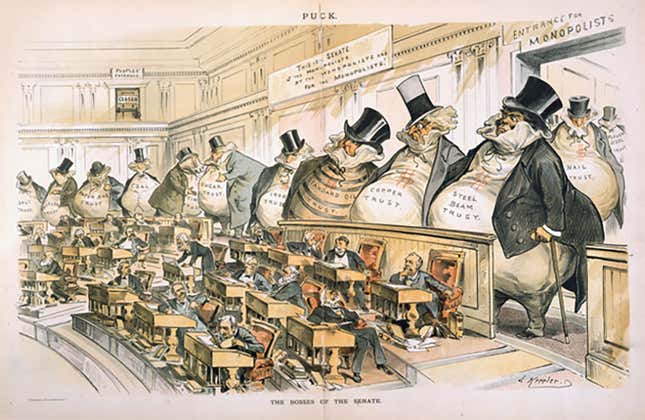

Fostering healthy competition is exactly the reason why the U.S. Congress passed the Sherman Antitrust Act of 1890. A trust was an arrangement in which shareholders of multiple companies in a single industry, oil for example, sold their shares in said companies to a single entity in exchange for a percentage of profits. The resulting single entity would then have control over the oil market, being able to set prices and gouge consumers as it saw fit. The first antitrust law, the Sherman Act, gave the government the power to take measures to break up unlawful trusts.

The Sherman Act was followed by the Federal Trade Commission Act, establishing the FTC, and the Clayton Antitrust Act, further prohibiting monopolistic practices including predatory pricing and anticompetitive mergers. Those two acts, both passed in 1914, along with the Sherman Act, continue to regulate U.S. businesses to this day.

Aside from the Federal Trade Commission’s normal scrutiny of any big corporate merger or acquisition, it’s unlikely that Microsoft’s proposed purchase of Activision Blizzard King will raise any red flags in terms of antitrust laws, any more than Microsoft’s purchase of Bethesda parent company Zenimax Media did back in 2020. Both the European Commission and the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission found Microsoft’s $7.5 billion Bethesda buyout raised no competition concerns, and the Activision Blizzard King sale should follow suit.

Why not? For one, there is no dearth of competition in the video game industry. From a software standpoint there are plenty of studios, big and small, creating games across multiple platforms, and Microsoft owning Call of Duty, World of Warcraft, Overwatch, Diablo, and Starcraft isn’t going to change that.

And yes, Microsoft is one of the big three console makers, but nothing is stopping another company from stepping in to offer something new. Would it succeed? Probably not, but that’s a result of the way the industry has evolved over the past several decades rather than some shadowy back room agreement between Microsoft, Nintendo, and Sony. Probably.

If you want a more qualified answer, IGN spoke to Gamma Law’s David Hoppe, a media/technology law expert, who called the Microsoft/Activision deal an example of “vertical integration.”

“The acquisition is another example of so-called ‘vertical integration’ in the video game industry–a console manufacturer (distributor) acquiring a game developer (producer). Of course, this is the largest such deal in games industry history, but U.S. courts have historically been unwilling to apply restrictive antitrust principles to vertical transactions,” Hoppe told IGN.

Microsoft buying Activision Blizzard King is a huge deal that some consider a sign of the industry’s inevitable consolidation, but it’s not hugely anti-competitive and certainly not a step toward total domination of the video game industry. Even if Microsoft manages to create the ultimate collection of high-profile publishers, swallowing up the likes of Electronic Arts or Take-Two, it’s not a monopoly until the FTC sings.

Unless Microsoft purchases Ubisoft, current license holder of Hasbro’s Monopoly board game. Then we’re all screwed.