I have never felt more in tune with a video game character than when Disco Elysium’s detective protagonist, his morale utterly devastated after a series of failed skill checks, tells his partner to fuck off and prematurely brings the game to a close.

Disco Elysium: The Final Cut arrived on PlayStation 5 (as well as PlayStation 4 and PC) last week, finally giving me a chance to comfortably play the game in front of my television rather than at the same desk I use for my job. After quickly working my way through the bits and pieces of the early game I’d already seen after Disco Elysium’s original 2019 launch, I’ve made steady progress as a bumbling, amnesic police officer with suicidal tendencies and a fervor for socialist politics.

My current goal in Disco Elysium is asserting my authority to a group of striking dockworkers so they’ll give me information. Unfortunately, these just aren’t any dockworkers, but the Hardie Boys, a group of enforcers who act as the de facto law enforcement in Martinaise, a small neighborhood controlled entirely by their union. I do most of my talking with the Hardie Boys’ gruff leader and namesake, Titus Hardie. He knows my character has no real authority in these parts, so it hasn’t been easy extracting details about the murder that forms the crux of the game’s story.

As a point-and-click role-playing game, Disco Elysium is built around conversations, small logic puzzles, and skill checks. What sets Disco Elysium’s skill checks apart, however, is that the game does them constantly, even without your input. These checks—which break typical RPG stats down into a collection of 24 specific attributes like Savoir Faire and Empathy—mostly just affect the flow of dialogue in humorous ways. But sometimes, failing these obstacles results in taking damage, either physically or psychologically.

Disco Elysium has what are essentially two life bars: one that functions as a more traditional health indicator and another that represents your character’s psyche. But unlike horror games, which often put an emphasis on a loose concept of sanity, this psychological meter is tied to the protagonist’s morale. When his physical health is depleted he has a heart attack and dies, whereas a complete dissolution of his mental health results in the detective walking away from his responsibilities to pursue a transient life of drinking heavily under a bridge and yelling at passers-by.

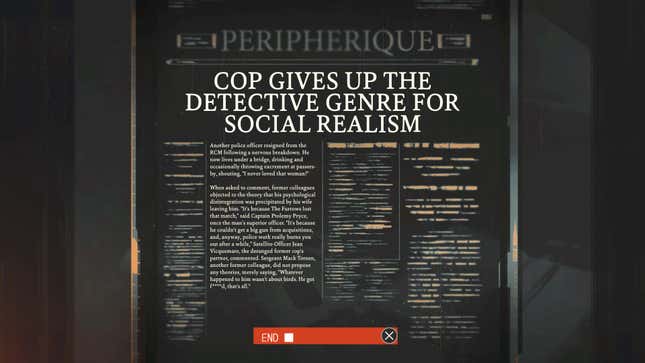

The harder I push Titus, the meaner he gets. Disco Elysium’s main character is a bit of sad sack, at least in my game, and isn’t built to excel in these kinds of interrogations. With every failed skill check and Titus’ subsequent mocking my detective’s morale sinks deeper. Curious about what’ll happen, I keep going without healing. After leveling up and unlocking a new attempt at Titus, my character again fails, pushing his morale to zero. As the screen darkens, I’m given just a few more conversation options. I tell my partner, Kim Kitsuragi, to fuck off. The last thing I hear before a newspaper clipping fills me in on my character’s new pastime—the whole bridge troll thing I mentioned earlier—is Kim, already at the limits of his patience with my bullshit, finally breaking his measured tone and responding angrily in kind.

“Giving up” is a concept I’ve toyed with routinely over the last year. As the United States sank deeper into the throes of the covid-19 pandemic with almost no help from the government in containing its spread, I often couldn’t understand the “point” of anything. And with these feelings of helplessness came both shame and guilt. Kotaku hired me in February 2020, just before the world entered quarantine, and for the last 13 months I’ve been able to support myself writing about video games from home. I’m not a nurse on the frontlines administering treatments to dying patients. I’m not a grocer forced to deal with rushes on food and toilet paper because they can’t afford to leave their now extremely dangerous job. My increasing depression, anxiety, loneliness, and exhaustion (as valid as they may be otherwise) are embarrassing reminders that I can’t even hack a relatively stable life without looking for a way out, metaphorical or otherwise.

Among the numerous things Disco Elysium does well, I think it’s particularly neat there’s a game over screen that doesn’t kill off the main character or see them “go insane” in a hackneyed way. Life is more complicated than that. Failure in Disco Elysium is part of the fun, a way for players to see how far their individual detectives can sink while still being able to solve a gruesome murder. But everyone has their limits. A human being, even one who is already as delinquent as Disco Elysium’s anti-hero is when you find him, can only be pushed so far until the self-preservation node in their brains is overridden by the need to escape, to leave, to just get away, no matter the cost.

Whether that means quitting a job, living under a bridge, sinking even deeper into addiction and mental illness, or something more drastic all comes down to the person, I guess. It’s exceedingly rare for a game to touch on these topics so poignantly, which makes me appreciate Disco Elysium all the more.