If you do anything for Halloween this weekend, chances are pretty good you might see a child (or an adult) trick-or-treating (or partying) dressed as a ninja. Maybe it’ll be a generic ninja, or maybe a specific one, like a Naruto character or a Ninja Turtle.

Today, ninjas are all around us. They’re in our movies and comics and video games; they’re even in our everyday language (“I can’t believe you ninja’d that in there at the last second!” “Come join our team of elite code ninjas!”). Far from their origins in medieval Japan, ninjas are now arguably that country’s most famous warrior type. We talk about pirates versus ninjas, after all, not pirates versus samurai.

There’s a huge divergence between historical ninja and the fantasy ninjas of popular culture. For example, everyone knows that ninjas were warriors who stuck to the shadows and never revealed their secrets— yet watch some anime or play a video game and you’re likely to see ninjas portrayed as the flashiest, most conspicuous characters around.

Like a lot of well-known fantasy archetypes, the ninja have a real history, but aside from some basic core attributes, writers and artists around the world feel free to interpret the word however they want.

The two strains of ninja—“real” ninja versus pop-culture ninjas—aren’t as separate as you might assume. In fact, the tension between the two is one of the things I love most about them. Ninjas as we know them today are a complex mixture of historical inspiration and modern imagination, defined by the intersection of two seemingly contradictory identities.

The true story of the ninja is fascinating. The people known today as ninja (they pronounced it “shinobi” then) rose out of small villages in the Iga and Kōga regions of Japan. By necessity, they became experts in navigating and utilizing the resources of the dense mountain forests around them. Because of their relative isolation, they served no lord and ruled themselves through a council of village chiefs. In the Warring States period (c. 1467 – c. 1603), people from these areas frequently found work as spies and agents of espionage, work that made good use of their skills in navigation, observation, and escape.

The villages of Iga and Kōga were eventually attacked by one of the greatest warlords of the era, Oda Nobunaga (an event that forms the loose inspiration for, among many other things, the underrated Neo Geo fighting game Ninja Master’s[sic], by World Heroes developer ADK).

The villages banded together and fought the invading armies with guerilla techniques—techniques enabled by their superior knowledge and mastery of the terrain. That’s pretty much textbook ninja action, right there.

By the end of the Warring States period, the ninja were enfranchised and integrated into the government’s systems of power. Their most famous leader, Hattori Hanzō, received an official salary equivalent to millions of dollars today. He became so much a part of the establishment that they named a gate in the Shogun’s palace after him, and today there’s a train line named after that gate: Tokyo’s Hanzōmon Line.

Serious researchers and students of ninja history and practice often take pains to remind us that the real-life ninjas they study were decidedly not cartoon characters. The real story of the ninja, they often say, is better than anything that’s been made up about them. That’s true in some sense: the history of the ninja is definitely worth understanding. It weaves together many threads of Japan’s culture, its philosophy, and even its spirituality.

But I have to admit: I love the goofy pop-culture version of ninjas, too.

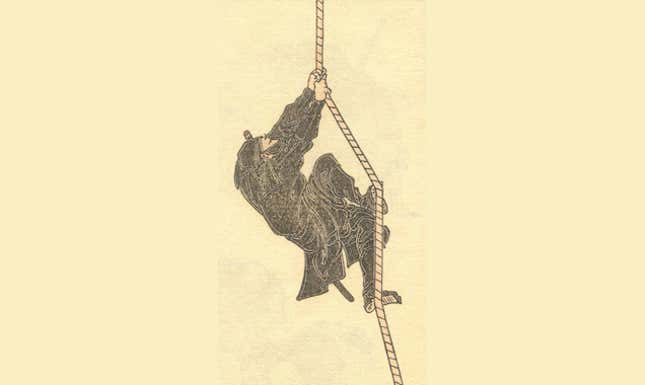

A couple hundred years after the people of Iga and Kōga took on Oda Nobunaga, the ninja had become mostly obsolete. It was a time of peace, and nobody ordered many spy missions or assassinations anymore. This was when fanciful illustrations of black-clad ninja began to show up in woodblock prints by artists like Hokusai and others.

Then, in the 1950s, a popular light novel called The Kouga Ninja Scrolls pushed the ninja far into the realm of fantasy. It was about star-crossed lovers who came from rival ninja clans. Each warrior of each clan had their own weird superhuman techniques: one of them could slice through his enemies with magic strands of women’s hair, one of them could breathe poison from her mouth, and so on. It was sort of like the X-Men—everyone had their specific power, they all had tangled histories with each other, and the outside world feared and hated them.

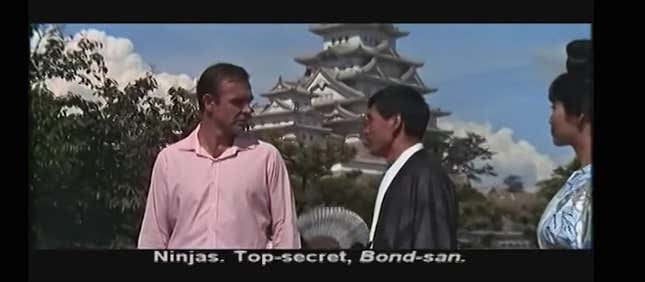

Ninjas continued their pop-cultural ascent in the west thanks in part to Ian Fleming’s James Bond novel You Only Live Twice, though it was probably the 1967 movie adaptation that had the greatest impact. It featured “Japanese secret service ninjas,” hilariously shown training “in secret” in broad daylight on the lawn in front of Himeji Castle, one the country’s biggest tourist sites.

By the 80s and 90s, ninjas were more or less loosely understood as the product of a school of martial arts you could take called ninjutsu (“nin techniques”). American-made stories featuring ninjas like Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles, 3 Ninjas, Surf Ninjas, Beverly Hills Ninja, Mortal Kombat, and so on contributed to the ninja’s rise to fame, even if the portrayals were not always very... elegant, shall we say.

Let’s pause for a moment to meditate on a particularly fine example of ninja cinema. This is a compilation of scenes from the 1987 Hong Kong film The Ninja Showdown:

(Man, where do I start with this thing? The way they talk? The way they run? The fact that they’re all white? The headbands that literally just say “Ninja” on them? The part where they throw actual frisbees at each other? The part where the dude just stops and shouts “Niiiiiinjaaaaaa!” at the sky?)

The Ninja Showdown may be the epitome of silliness, but it can be difficult to make a non-campy ninja movie. A lot of the actions we equate with ninjas are a stone’s throw from physical comedy—we visualize fanatical acrobats vanishing into shrubberies, sticking to ceilings, willingly swimming through sewers. There’s something darkly amusing about fatal surprise, too: if you’ve ever played the original PlayStation ninja classic Tenchu, you’ll no doubt remember the hapless samurai who good-naturedly intones, “Nice night!” just before emitting a clipped gurgle as you slit his throat from behind. Perhaps it’s best to accept that there’s something inevitably camp about pop culture ninjas (as there is with all of the ninja’s Halloween costume kin: vampires, zombies, etc.).

Today, comic book-style, super-powered ninjas are the norm. If you play video games, you’ve no doubt seen them all over the place: there’s Hayabusa from Ninja Gaiden and Raiden from Metal Gear, both of whom can slice through tanks and helicopters with their swords.

There are also plenty of knock-off versions of those characters–who remembers Ken Ogawa from forgotten 2009 Xbox 360 exclusive Ninja Blade? I do. Look at this poor guy:

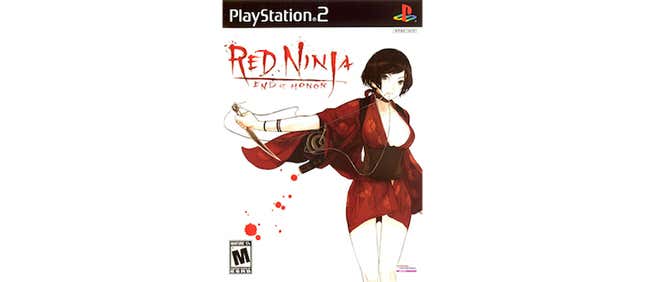

Then there are the “fan favorite” lady ninjas (sometimes called “kunoichi”) like Dead or Alive’s Kasumi and her half-sister Ayane, or King of Fighters’ Mai Shiranui. Why are the costume designs for female ninja often so... fanservicey? A lot of creators seem to feel that female ninja are okay to treat as sex objects. That’s not something that was invented solely in the modern era—serious ninja tomes almost always do a little nodding and winking about the role women could play in spying by mentioning that seduction and “feminine wiles” are perfectly effective espionage techniques.

Of course, in medieval Japan, it was a given that anyone important enough to be targeted for assassination or interrogation was most likely a man, and sure, maybe this approach worked sometimes. I’m pretty certain the ninja women of 15th century Japan didn’t dress anything like this, however:

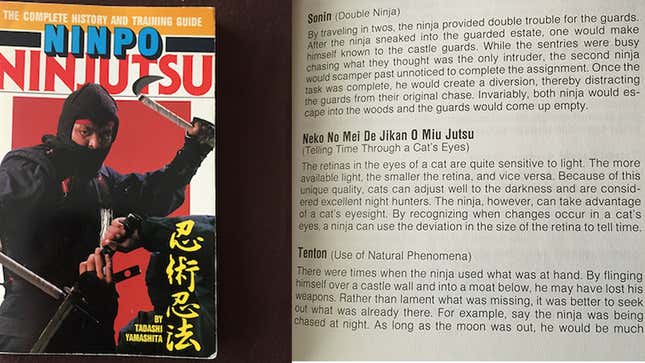

Sometimes ninja facts and ninja fiction run together in confusing ways. For example, the 100% serious 1984 book Ninpo Ninjutsu: The Complete History And Training Guide says one ninja technique involves telling time by studying the dilated eyes of a cat:

“The ninja, however, can take advantage of a cat’s eyesight,” the author writes. “By recognizing when changes occur in a cat’s eyes, a ninja can use the deviation in the size of the retina to tell time.”

This brings up so many questions for me. Will a cat just magically show up when you need to tell the time? If you’re sneaking around, how do you get the cat to look at you so you can see its eyes? Is looking at a cat easier, somehow, than looking up at the moon or the sun? What if it’s dark or the cat is far away? What if the cat has just been inside a building? And even if this technique does work, why is it important enough to mention now, where the modern ninja on a mission is more likely to have a Casio digital watch than an easily accessible cat?

The whole cat-eye-clock thing is just one of the many strange nuggets I come across anytime I start looking into “authentic” ninja materials. Is it real? Do the people writing these books really think ninjas found this stuff handy? Will tricks like these really work in the field? The lineage of today’s teachers of ninjutsu are difficult to verify because the ninja (for good reasons) kept few records. You can find a whole lot of controversy and accusations about the provenance of many current ninjutsu schools, if you want to go looking.

The two strands of the ninja–factual and fictional–aren’t as separate as they might seem at first. That’s actually the best thing about them: almost all ninja characters and stories build upon the history and lore that came before them. When you watch Sonny Chiba play Hattori Hanzō in Kill Bill, you’re watching the director making an homage to previous film portrayals of Hanzō... which themselves were based on popular historical fiction... which themselves fancifully reinterpreted the real historical figure.

Every time you experience a ninja story, you’re biting into a metaphorical spanakopita comprised of thousands of filo-dough layers of imagination, abstraction, and (at the very center) a band of historical truth. When I watch, play, or read something with ninjas in it, I can see how the creators have carefully (or carelessly) picked which parts of the ninja myth to continue and which to let go. Their “ninja” could be a historical Japanese warrior, or a time-bending, tank-slicing superhero. Or maybe just a new startup hire who’s really good at coding.

That’s why I love ninjas, in spite of all the inaccuracies, fantasies, and the inherent goofiness they invariably bring with them. The reality and fantasy of ninjas actually work together and enhance one another. Reality inspires fantasy, and fantasy (sometimes) gets people thinking about reality. Ninjas have survived and thrived in the popular imagination by being highly malleable. They loom large in our awareness but expertly avoid formal definition. That’s probably just how a real ninja would want it.

Matthew S. Burns is a writer and game developer in Seattle. Follow him at @mrwasteland and see his other work at Magical Wasteland.

Illustration by Sam Woolley.