Video games have a blackness problem. This has been a known thing for a while, and we do talk about it from time to time. But I'd like to keep talking about it.

When they appear at all, black video game characters are often reduced to outdated, embarrassing stereotypes. It's commonly accepted that part of the reason for that is that there simply aren't enough black people making video games. Surely if that changed, video games' depictions of black characters would improve, right? What else might it take?

I decided to email with several prominent black critics and game developers to start a conversation. What is the source of video gaming's blackness problem? What is to be done? I enlisted games researcher and critic Austin Walker, Treachery in Beatdown City developer Shawn Alexander Allen, Joylancer developer TJ Thomas and SoulForm developer and Brooklyn Gamery co-founder Catt Small to talk about what we all thought. Our conversation, which took place over email, follows.

Evan Narcisse (Me):

Actual black people don't seem to have had very much to do with creating my favorite black people in video games. Or many other people in games, for that matter. That bothers me.

In other art forms, it's possible to trace a long history of black people crafting their own stories in the face of a system that tried to suppress them. Sometimes those stories were straightforward chronicles of existences lived under oppression, like Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl. Other times, writing a book, making music, movies or TV was a means to calling out the structural injustices of living in America. Those things aren't mutually exclusive but it's tended to be easier for one sort of endeavor to find institutional backing and support. The thing about Assassin's Creed: Freedom Cry, for example, is that it's got the distance of history to make it more comfortably consumable. You can safely cluck your tongue and sigh about how rough black people had it in the ol' slavery days. You don't have to acknowledge how the systemic legacy of the laws that prevented black people from voting still lives on today with election fraud.

I've written before about the desire to see more black faces and different kinds of black stories in video games. That desire's changed a bit in the last few years for me. I keep thinking about how AAA games get made and the invariable, invisible compromises that happened along the way. When I think about black characters and visions of black life in video games that resonated with me—whether it's Adewale or Aveline from the Assassin's Creed games—I have to reckon with the idea that they was very likely no black person making decisions about those characters.

Because I've written about this stuff before, I've had some weird experiences over the years where developers would e-mail me about their games. It's been either "hey, it's okay if we have a funky black person in our game, right?" or "Evan! Look at this black person in our game! Tell the world!" That alone hasn't been enough for me to get excited to enough to follow up with the people involved. I also tend to resist the easy narrative that people seem to want to invoke, which seems to be that a simple aggregation of more black faces gets my stamp of approval. I'm just one guy who's lucky enough to voice his feelings publicly. I'm not a spokesperson but when I do write pieces like this, this or this, people tell me that I'm speaking part of their experience too.

For a while last year, I felt guilty about not playing Watch Dogs. It was set in Chicago, a city that's racially polarized in the most tragically fascinating ways. I didn't expect a high-risk, big-budget franchise starter to try for anything daring with regard to how it rendered black lives. (Remember Liberation and Freedom Cry debuted on the sidelines—on the Vita and as DLC, respectively—and not on the biggest possible stages.) But, friends who played Watch Dogs told me how retrograde the projects-dwelling Black Viceroy thugs were, like bogeymen kludged together from decades of the worst stereotypes. So much for progress, I thought. And the guilt went away. Because why should I feel like I have to have something to say about a game like Watch Dogs when it doesn't have something to say about black people?

That element of Watch Dogs was just another thing that made me feel like an outsider in video games, despite the fact that I think and write about them every day. What I've really been craving have been games that make me feel the opposite way, something that leverages any of the myraid modes of modern blackness. One of my favorite books—The White Boy Shuffle by Paul Beatty—does that really well, moving through suburbs, rap videos, academia in a hilarious satire that still nails some home truths about how black people are portrayed in the media. Black lives exist everywhere in every strata of society, in all sorts of strata, ways and methodologies. Corporate video games still have yet to even scratch the surface of that. You've written about Watch Dogs, Austin. Do you think the black characters in the game could've been more than what they were if more black people were involved in its development? Or is the big corporate machinery that makes and moves a game like that too big to avoid pitfalls like that?

Austin Walker, game critic:

Evan,

Maaaaaaan, I think Watch Dogs could've had better black characters even if there weren't more black people working on it.

Lots of noise was made of how Watch Dogs' map of Chicago doesn't really line up with the real city. Well, the question for me is, what maps were the developers working from? Well, if their depiction of the inner city (and thus their only depiction of blackness) can be a clue, then their maps might have been the sensationalist TV tabloid stories of the early 90s.

In those depictions, Chicago's Cabrini-Green projects (clear inspiration for the Rossi-Freemont Towers in Watch Dogs) were a lawless battlefield where young black men sold crack and shot at cops and harassed neighbors. But these alarmist stories never actually linger on the neighbors, do they? They show the white chalk outlines on the street on the day after a murder, but not the block party held there just last week. We get photos of brothers in cuffs, but never holding open doors or helping folks with their groceries. Listen, Cabrini-Green, by all accounts, had lots of problems. But it was also a place where people lived their lives.

(Photo by Tim Boyle/Getty Images)

There's a solid New York Times story on the destruction of the final Cabrini-Green tower, focusing on the conflicted feelings the community. About halfway through, there's this bit from a girl reminiscing about her time living there: "There were block parties. There were Old School Mondays, where everyone would come back; people who had been gone for 25 years would get together. I remember my first Christmas there. And this little area called the Blacktop, where I learned to ride a bike." Watch Dogs has no room for little black girls to learn to ride bikes. As Kirk Hamilton pointed out in his review last year, black people in Watch Dogs "exist simply to kill or be killed, or occasionally to engage in sexual assault while on camera."

This is what I mean when I say that Watch Dogs could've been better even without more black folks on the dev team. When non-black people want to learn about the experience of blackness, they often seem to turn to source texts that, themselves, could've used more black folks involved in the creation. Texts that focus on the tragedy instead of presenting a holistic view of life. Part of this is, as you suggested, the "big corporate machinery" behind a game like Watch Dogs. It might have been way easier to arrange a viewing party for a mediocre old documentaries than it would've been to justify an expensive trip to interview the folks who actually lived Chicago.

But, the result, in games like Watch Dogs, is that blackness is presented as pathological. The black spaces are violent, ruined, and dangerously mysterious. The black characters, at best, overcome that violence through exceptional intelligence or talent, or, at worst, give into their darkest urges. Sometimes there's a degree of sympathy in this sort of depiction: "Wow, look at how bad they have it." But what we really need—in games as well as in other media—is something more complex than this image of devastated black lives. And yeah, part of the solution there could be more melanin in game development.

It's interesting that you mention the history of black folks creating our own art in oppressive contexts—sometimes specifically in opposition to forces that wanted to keep us from creating it, or who wanted to own what it was that we created. We weren't allowed to learn to write because it would offer us dangerous weapons like private communication, careful record keeping, and long-form thought. Our music accompanied and eased our work, or it broke free from the brutal rhythms of the factory. Our films reflect the complexity of our heritage. I don't know about you, but I heard these sorts of stories as a kid a lot.

But there isn't a version of this story for games yet. The closest we have is the story of being good at playing certain games: the cousin who got to be a defensive tackle on an NCAA team. The uncle who played ball overseas. The brother (or sister! Or non-binary black person!) who could kill a cypher (because let's not forget that the unwritten rules of freestyle rap have as much in common with improvised games as with music). Maybe the closest thing we have are stories where players transcend and "change the game forever" by shifting the conventions. But we don't even have these stories for digital games, yet, even though lots of black folks play them. I'm not saying I'd settle for someone black to be on the winning team at The International 5, but it'd be something.

Mostly though, I'm ready for games to offer a more complex vision of blackness. In another recent letter series (and I know, it's a faux pas to link to one letter series from another), I wrote about the broad range of material that appears in the "blaxploitation" catalog. This is what I want for blackness in games: Recognition that the struggle exists, but that it exists in the lives of complicated people, not caricatures. Maybe with Liberation and Freedom Cry, we've seen the extent to which the Ubisoft Formula can serve that desire.

So, on that note, here are MY questions: what might a complex and (dare I say) compelling vision of blackness look like in a genre other than open-world-stab-'em-up? Alternatively: have you played anything lately where the variety of blackness felt represented?

I'm guessing no, but listen, a dude can dream.

Shawn Alexander Allen, developer:

Hey Evan and Austin,

These are great questions, and they reflect my lifelong journey of self-discovery of my own blackness and the ever-present questioning of what does blackness even mean.

I used to work at an EB Games with 2 other black employees and we had a large black customer base. A bunch of us went to see the movie Barbershop together, which was interesting because there were a lot of parallels between my store and the film in terms of the community and the comfort everyone felt with each other. Barbershop is a movie that questions what blackness is at every turn, even so far as to ask if a bubble coat wearing, hip hop blaring white man can cut black hair better than an uppity cappuccino drinking black barber.

To start to tackle this subject in games I can't help but recall season 4 of Boardwalk Empire. I'm not sure if you're familiar with it, but Boardwalk Empire is a show primarily about Prohibition-era Atlantic City and the booze-running done by numerous criminals including main character Nucky Thompson. Series mainstay and self-made black community leader Chalky White, played by Michael K. Williams, worked closely with Thompson before Prohibition to help the black community as much as possible and over time became one of Nucky's most trusted employees.

In season 4, Chalky was now being challenged by one of his lower-class henchman by the name of Dunn Purnsley, who was being egged on by a vastly more educated black revolutionary named Dr. Valentin Narcisse, a character mirroring W.E.B. Dubois. The season, while still focusing on the problems of prominent white characters, took a divergent path to involve multiple black men and women of different classes and—while ultimately problematic in how it abbreviated and streamlined important black characters in our history—it was still refreshing to see on a show that was ultimately about rich white men fighting over who would get more rich or die trying.

This is not something new to HBO, with a show like Deadwood that featured a couple of black folks who were still notable cast members and, of course, The Wire which has an amazing array of characters on both the good and bad sides working to find their way in life however they can within the systems that they are surrounded, and often trapped, by.

I bring all of this up because while HBO is probably the best representative of "mature" media that takes cues from cinema to deliver worthwhile experiences at a premium to the average consumer. At the same time, we also had Breaking Bad which was essentially 'what if a white guy from New Mexico became a drug dealer because he had bills to pay,' a.k.a. shit that happens in the hood all the goddamn time. Games seem happy to continue the idea of white anti-heroes surrounded by supporters with the one black guy here or there, instead of going the HBO route and creating places where black lives can have their own agency.

I'm very disappointed in Watch Dogs, to the point where I will never pick it up. After reading Ta-Nehisi Coates' argument for reparations and having visited Chicago in December and hanging out with some of the hip-hop community out there, I just see Watch Dogs thematically as something of a failure from the very concept.

It could have easily been a game starring a black guy who left South Side but had some gang violence that dragged him back in, and as much as it is pernicious to constantly drape that trope around the necks of black men, it could have immediately been about something more meaningful. It could bring more attention to things that are going on in our current events; I talked with one dude whose brother was killed in August. That murder messed him up, as he had also just become a father. These are very real things, and could have actually started a conversation. Honestly, from a cultural point of view, Watch Dogs feels like shallow fodder that has since been forgotten.

Rewind to the early to mid-2000s and we have a few more black characters, many in leading roles, who were nuanced, and may have dealt with another black person who wasn't just like them, or from their hood and were given more of a spotlight.

In 2004, we had a fluke of Chronicles of Riddick: Escape from Butcher Bay and The Suffering being released almost back to back. Both games featured biracial black main characters, Riddick and Torque, who were prisoners. Even still, we as players were given many clues up front that each guy also had redeemable qualities. In the case of The Suffering you ultimately can determine if Torque is innocent or not by being a good person in the game, and showing restraint with the use of the overpowered monster form.

Now, in the middle of the 2nd decade of the new century we're struggling to even get that far.

It's true that we have a game like Mass Effect which has Keith David as Colonel Anderson, and our crew member Jacob in Mass Effect 2, but Anderson is a tool to guide Shepard and hardly exists outside of being the mouthpiece for recommending the player to be more than he can ever. Conversely, Jacob never interacts with Anderson in any meaningful way and he himself has the harmful trope of daddy issues which is what his whole loyalty mission is all about.

Interestingly enough, we have two games released fairly recently that feature some of the strongest black characters in games. They have more interesting parent issues but it's not just dudes again: one stars a woman and the other a little girl. Nillin stars in Remember Me and Clementine is heavily featured in The Walking Dead, Season 1 and goes on to star in Season 2. In Remember Me, Nillin confronts her black mom, the head of the evil corporation she has has to destroy, and in Walking Dead Clementine meets Lee and learns her parents were killed and eventually has to set out on her own after her new adoptive guardian passes as well.

These games represent something fairly unique, but also unfortunately shared a big problem. While the parent types are voiced by black actors, Orlessa Altass as Scylla Cartier-Wells (mother to Nillin) and Dave Fennoy as Lee Everett (adoptive father to Clementine) respectively, both Nillin and Clementine are voiced by white actors quite literally removing their blackness. I have caught a lot of backlash mentioning this, but my argument always is, would you put brown makeup on a white actor to cast them as a black character in this day and age? The answer is obviously no.

As the previous would be considered blackface, casting black characters with white voice actors is what I coined "digital black face". It removes everything from the character, and only perpetuates that games are so white, that they can't even find actors to play the occasional black character. Saturday Night Live caught hell for this, why not games?

All of these issues that games have today seem to continue to be wrapped in a 'one step forward, two steps back' mentality so that we're never actually moving forward. While a show like Empire will come out on Fox and do better week after week, we're still making games that don't even try to star multiple black characters.

I want to leave this open for more feedback, as this brings up a big question for me. While I am focusing on having a black main character in my game Treachery in Beatdown City who eschews the normal stereotypes of black male characters, I could never fault another black creator for not necessarily wanting to do the same because, after all, we want to be able to make whatever we want as creators.

Despite the dearth of representation that the games industry has, my limited times of feeling a connection with a protagonist and as a part of the culture as a whole, I didn't start making games to really make a difference, and I'm sure not many game developers of color do either.

As many game designers are wont to do, I began thinking of my old favorite games and genres that were ignored and said "I'll do that but with a twist!" Treachery in Beatdown City started off with a focus on creating unique combo mechanics, and not so much on who I am, how I fit in with the industry or if I wanted to do something to feature more black and brown folks, because well, why should it?

When I started, though, something made me decide that I was going to make our character Bruce be the exact opposite of what a black character would normally be regarded as in a game; I wrote him as a rich stock broker who is also an otaku and worldwide traveler. Part of this came from the fact that I had a lot of time to flesh out my characters: I spent years doing so before one line of code was laid down in Game Maker, or C# as it is today. I think I was also just tired of seeing the same ignorant, brutish black characters in games who can't use computers, curse up a storm and are otherwise one-dimensional.

As I keep working on Treachery in Beatdown City, and I keep talking about it and race in games in general, it has become more and more apparent that so many designers and artists, particularly black people, want to see more black characters in games. They want to create them, they want to be them. At the same time just seeing a dude like me up front talking about this has convinced other people to come out of their shell and become more active in the community.

It essentially boils down for me asking the question, how do we encourage more black characters in games? More stories that feature black characters? Especially when we make up, what, less than 2% of the developer population? If established studios with the funds to take risks are pushing black content to DLC, blackface skinning (John Stewart Green Lantern DLC skin in Injustice), or just not even willing to take the same risks to create a new character who is black to lead a franchise, especially when money is one of the biggest factors in making games, how are we going to encourage anyone else to take those steps?

TJ Thomas, developer:

Y'all,

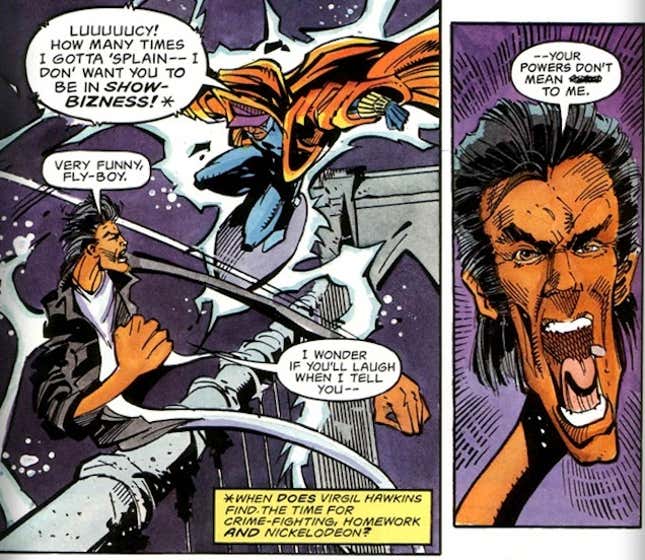

Growing up, I didn't really understand the importance of representation. Even until I actually became an adult, I still didn't really understand. But as I grew older and began deconstructing my own racial ideologies (and by extension my own blackness), I began to realize that I didn't partake in much Black media, or media with Black protagonists... but the few that I did left a total mark on me growing up, and I didn't even recognize it until recently. I'm sure that most Black creatives are with me when I say that Static is probably one of the most important superheroes to ever be published by DC. Here's a Black teen just trying to live his life normally, but not only does he have to deal with being a superhero with a secret identity, he also has to deal with the realness of being a Black teen in modern America. He and his family are affected by real-world problems affecting Black people even today, and all of these facets influence who he is. That unique experience that he has compared to most other superheroes is what makes him stand out so much, and it's something that just wouldn't work if Static were white.

I don't really care that much about superheroes enough to explore the medium, but Static is someone that i'd make an exception for, simply because I'm just so invested in the character and the writing. It's not just because it's good writing, it's because it's something that I can relate to on a personal level. I can see "me" in Black characters, much like white people see "themselves" in white characters.

The way I look at games is pretty heavily bent more towards play and action over story, although I do wonder if it's because of this. With so little representation, I don't really see myself as these white characters. I just see myself as exploring the story of a white character. Which is fine, really, but it personally makes it harder for me to get genuinely invested in the characters. and when I can't get invested in the characters and the story, I get invested in the mechanics instead, and that's usually where I find the sweet center. But as great as that is, I'd like to have more snacks once in a while that are like that sweet center, but it's the whole candy, y'feel?

However... I find it's gonna be really difficult to encourage more people to make black protagonists. Like you said, Shawn, you can't force a person to make their characters black. Everyone has their own motivations for creating a character, right? Rather, I challenge creators to ask themselves why. When you're working on a character design, do you always imagine them as white, or having white skin? If so, why? What's your reasoning for that? Without every creator deconstructing how they view their own ideologies towards race, nobody is going to care enough to deviate from "the norm." If people don't see what the problem is in making predominantly white characters in their art— especially if you're going to get involved in games where we have Real, Hard Stats that say that Black and Latino people tend to play (console) games on average, if not more than white people— then why would they ever explore outside of that spectrum outside of stereotypes and tokenized characters?

Catt Small, developer:

Everyone's mentioned things that I relate to so much.

As TJ said, it's quite difficult to encourage people to make Black characters, especially if they've internalized the concept of whiteness as the norm. I'm excited about several recent games featuring complex Black people, including The Walking Dead, Broken Age, and Sunset. I hope these games inspire people to rely less on tropes and treat Black people as humans with a variety of emotions and experiences.

One way we'll see more good Black characters in games is by making the industry more accessible. As Shawn said, the number of Black game developers is depressingly small. I don't think there's a dearth of Black people who want to make games, but rather a dearth of Black people who have the encouragement, time, and money to invest in making games. Many Black people are risk-averse due to factors including a higher likelihood of poverty and therefore encourage their children to go into fields such as science, law, and teaching. How do we enable Black people to make games and succeed financially, and how do we change the perception of the medium itself so parents don't discourage their children from going into game development?

The spread of free and low-cost tools is helping to introduce more Black people to game development, but visibility and transparency in the industry is also helping. For example, Shawn's been speaking at conferences. I've spoken about game development at several colleges in Black and Latino communities. During each presentation, I not only discuss how to make games and tools they can use, but also events they can attend to become a part of the community. I also collaborated with Black Girls Code through Code Liberation to organize a game jam at which 57 girls learned to make games. More initiatives like this will hopefully enable Black people to tell their own stories through games.

Like TJ, I heavily gravitated toward Black characters in other forms of media while growing up. Patti Mayonnaise, the brown-skinned love interest from a 90's cartoon called Doug, showed me it was okay to cross racial lines and that I could be attractive to people of all kinds. My parents let me watch Gullah Gullah Island, a live-action show, as much as I wanted because it featured a Black cast and taught me about the Gullah culture of my father's family.

As a teen, Static Shock and Green Lantern from the Justice League got me into watching superhero shows. Peach Girl, a popular manga, helped me understand colorism and respectability politics. The Boondocks comics helped me understand how varied blackness could be – you can be politically active, marry a white person, be a lawyer, wear an afro, wear locked hair, be bookish, be loud, be any number of things, but regardless of how you look or act you are still Black.

Coming back to blackness in games, Borderlands' Tiny Tina most recently struck a chord with me because of her upbeat personality, her (quite possibly unintentional) mixed-looking features, and the fact that she was raised by Roland, a well-respected Black male character. Tiny Tina really freaked some people out because of how she spoke versus how she looked, but I liked the notion that blackness comes in different shades and capacities.

Many people seem to think of blackness as a static thing. When designing Black characters, game makers should consume actual black culture – literature, documentaries, and movies created from our perspectives. Our identity is complex and deserves more than the generic portrayals commonly shown in the media. Shawn mentioned Barbershop, which was a hit at my majority Black and Latino school in Harlem. Shows like Empire and Blackish sometimes contain stereotypes, but also do a good job at showing the complexity of blackness by including themes such as colorism, sexism, and the struggle to rise in the world yet retain authenticity.

Just like Shawn, one goal of Prism Shell, a game I'm working on, is to quietly subvert Black stereotypes by featuring a confident, smart Black woman with punk rocker hair. On the intro screen, she looks straight at the player, forcing them to engage with her humanity. I'm also making a game that features a college-age Black woman navigating the worlds of race, gender, art, and tech. I hope to be contributing to a movement in games that portrays Black people as more than just city workers, murderers, and gang-bangers – we are not trash to be disposed of nor comedic relief, but rather a people with centuries of history and culture that survived despite many attempts to destroy them.

I think people need to be open to a variety of blackness. Black people don't speak or act in a single way, yet game makers still rely on tropes to make characters seem authentic. I'm sure others in this discussion have also been accused of "acting White" or called myriad things that allude to being less Black. As Cheryl Contee said in Baratunde Thurston's book, How to Be Black, "I've wished that other people could see me for the complex being that I am, not see past my race but see that and all of the things that I have done, to embrace all of me." Blackness is diverse and multi-faceted.

Kehinde Wiley also discusses diversity of blackness in Who's Afraid of Post-blackness?: "Sometimes Blackness is threatened by a desire to go outside of a collective sense of deprivation and to engage education and opportunity. It feels good to all be down with one another. This notion of being authentically Black is comforting." Despite that feeling of comfort, we need to create characters who break the mold and go beyond expectations. Stories beyond slavery, poverty, and gangsterism are still part of the spectrum of blackness. This is a point that the entirety of America needs to discuss, not just Black people.

Race is still quite a touchy subject –– gender diversity seems to be easier to discuss and less polarizing –– however, if we don't discuss it, we'll keep seeing the same tired tropes. I want games to be more and for developers to aim higher, regardless of their race. Each trope-defying character we create will have a palpable effect on the industry.

Evan here, back to wrap things up. The discussion isn't meant to solve all the frustrations that the participants and other people feel about the state of representation of blackness in video games. Hopefully, it shows why it's an important thing to talk about and illustrates possible ways to tackle the lack of blackness on screen and in development circles. Getting more black people in video games doesn't feel like the kind of thing that's going to happen via some sort of transformative messiah figure. It's going to take a lot of smaller steps and leaps of faith to become a reality and continuing to have conversations about it will be a vital part of that. Time permitting, I'm going to be following up with Austin, Shawn, TJ and Catt to talk more about what it feels like to play, write about and make video games while black.

[top illustration by Sam Woolley]