It’s been a terrible few weeks for the black body.

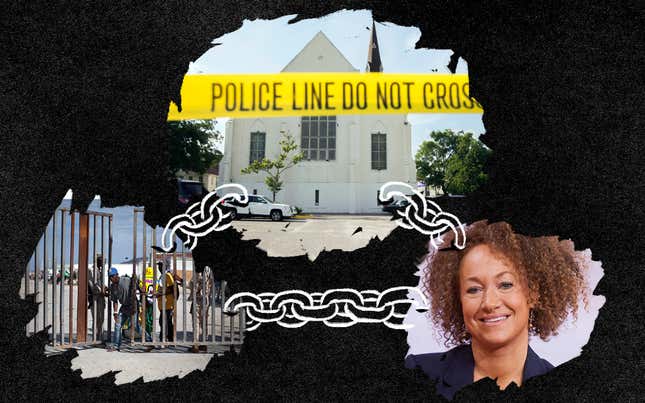

We’ve just been through a stretch of days that unambiguously demonstrate that black people in this country—and one other—can’t move, think or exist as freely as their non-black counterparts. A white woman claims that she’s always felt black on the inside, to the extent that she calls her own parentage into question. Black people of Haitian heritage in the Dominican Republic face mass deportation and disenfranchisement, despite the fact that many have never known life in any other circumstance than the one being ripped away from them. And nine black congregants were murdered inside a church that’s hallowed ground for the African-American freedom struggle, killed by a young, racist gunman who said that blacks were taking over the world.

Black people aren’t taking over any damn thing. If anything, it’s felt like the existential footing essential to living our lives gets eroded in big crashing waves after events like these. We’re not free to be our fullest selves. Not when the basic psychological agency needed to publically protest or grieve gets shouted down and undercut. The deaths of Michael Brown, Eric Garner, Renisha McBride and too many others at the hands of police—and the activist responses to those killings—have been followed by rabid efforts to re-frame their last moments and entire lives in the worst possible way. On paper, the freedom to air out our grief exists, sure. But it’s met by responses that seek to limit it. Say what you want, black folk; the Constitution allows for that. But don’t you dare invoke the insidious subtext of institutional oppression that drives you to speak in the first place.

Rachel Dolezal is free, to a wildly unfettered degree that lets her say she’s black. She at least gets the courtesy of debate. She’s gotten think-piece articles and televised interviews dedicated to investigating the peculiarity of her individual race problem. I’ve had lot of conversations with black friends over the last few days where we acknowledge that black identity is lived in an infinite number of ways and skin tones. And even as folks bat around the idea that race is a bullshit social construct invented centuries ago to stratify human beings into castes, the mechanism of that contraption still holds some people fastly in place. Not Rachel Dolezal, though. She gets to decide what she is.

The hundreds of thousands of Haitian-descended people in the Dominican Republic staring down the possibility of being deported aren’t free. Many of these people were born in the country trying to throw them out—children of immigrants looking for a better life. They’re in the grip of a centuries-long blood feud between two countries on the same island, one where a sugar colony threw off the yoke of slave oppression. Yet, these at-risk black people in the DR are back where their ancestors started, unable to steer their own lives and plant down roots where they find themselves.

Clementa Pinckney, Cynthia Hurd, Sharonda Coleman-Singleton, Tywanza Sanders, Myra Thompson, Ethel Lee Lance, Susie Jackson, Daniel L. Simmons and Depayne Middleton Doctor were not free in their last moments of life. They died like chattel, pawns in Dylann Roof’s attempt to start a race war. Their freedom to assemble and worship got overridden by the same hoary old myths about white superiority that have driven public policy and private discrimination in America since its birth.

I started writing this in the air over Denver on the 150th anniversary of Juneteenth, a day observed as a holiday memorializing the Emancipation Proclamation. Concerned as it is with the presidential order that said black people weren’t just property anymore, June 19th is a grassroots holiday that looks back at the bleak racial legacy of the American past. It’s a date meant to celebrate the collective strength that carried black folks through slavery.

This Juneteenth didn’t feel celebratory. It felt mournful. The pains of the past are reincarnated and upgraded, parading down black folks’ collective psyche in military-grade police gear and proudly carrying the banners of Jim Crow and apartheid. Right now, what I live inside feels like a sort of shadow freedom. A trap of weariness, doubt, fear and anger that I need to mask or suppress to get through the day. It’s a decaying simulacrum of the way I see other people living—seemingly carefree and unburdened—but hollowed out by the creeping fear of the exact moment I’ll have to explain to my daughter why someone brown got killed by a cop or a racist. Lately, it’s all I can think about. And that’s not very free at all.

Image by Jim Cooke, photos via AP.