The summer of 2022 was one for the record books. Wildfires raged across North America and Europe, tens of thousands died in brutal heatwaves, water in reservoirs dried up revealing bodies long forgotten, and flooding displaced millions. All of this is awful, and it seems likely that it will only get worse if nothing is done. Considering these clear, numerous, deadly warning signs that we need to drastically change our way of life or face increasingly apocalyptic levels of climate disaster, it’s astounding that more serious action isn’t being taken. Maybe it’s because we’re just waiting for our glorious post-apocalyptic future to arrive, one which modern video games are so eager to tantalize us with. There’s no point saving this world, because when the Death Stranding comes, we’ll get to live in rad Knot Cities. Or we can put our hope in the GAIA AI. Maybe a Vault will have an opening for someone with just our set of skills. Our options are endless!

Across the last decade or so, the world of the post-apocalypse has become increasingly common in video games, and although it’s hardly presented as a safe or beautiful future, it’s nonetheless established itself as a comfortable place for gamers to live. We can’t seem to get enough of imagined scenarios where humanity picks up the pieces after a cataclysmic event. The Last of Us, Fallout, The Walking Dead, Horizon Zero Dawn, Dying Light, Nier: Automata. These are worlds where humans survive in the wake of some calamitous happening. That so many game narratives are set in the post-apocalypse seems to say either we are resigned to, or content with, the idea that this is just where things are heading and there’s nothing we can do. But...why? This didn’t always used to be the case. What happened to narratives where characters try to save the world we’re already living in?

In the early- to mid-1990s, narratives in video games were beginning to expand. While most games of the time merely used story as the connective tissue between moments of gameplay, the RPGs of the era demonstrated that gameplay could play the support role in the telling of a story. It’s here, in these nascent days of video game narratives, where we see honest hope for a better tomorrow as a surge of environmentally focused stories took hold not only in video games, but in media at large.

Our World Is in Peril

These are the first five words of the opening narration of every episode of Captain Planet and the Planeteers. “Our world is in peril” doesn’t sugarcoat the message. Shit’s bad, y’all. The series, which started in 1990, brought environmental awareness to the Saturday morning cartoon block. The show was overt in its messaging by making the antagonists, the Eco-Villains, truly despicable. Each villain represented a facet of society that was slowly poisoning the planet, from Looten Plunder’s deforestation and unethical business dealings to Hoggish Greedly’s polluting schemes. Along with Stop the Smoggies—the French-Canadian animated show that pitted a group of plucky, nature-loving people known as the Suntots against a trio of polluting, greedy, oil tanker-dwelling humans—Captain Planet and the Planeteers brought environmentally conscious stories to a form of entertainment meant to sell toys to children in footie pajamas eating frosted flakes.

This was the first time that a number of environmental issues were front and center in the media and the public consciousness.

- The Chernobyl disaster in 1986 caused devastating long-term damage to both the people of Ukraine and Belarus, and the surrounding environment. After several crises that narrowly avoided becoming major incidents—like Three Mile Island—Chernobyl was the first accident to have a major release of radioactive material over a widespread area with lasting impacts.

- A hole forming in the ozone layer was first noticed in the 1980s. Ozone depletion brought on by chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs) found in a wide range of products, from aerosols to refrigerants, was determined to be a major cause. The normal ozone concentration threshold of 220 Dobson Units was being hammered by CFCs, lowering ozone levels to a record low of 73 DU in the fall of 1994.

- The Exxon Valdez oil spill off the coast of Alaska in 1989 damaged over 2000 kilometers of shoreline, with 10 million gallons of crude oil spewing into the Gulf of Alaska. The spill killed wildlife and made large swaths of the area uninhabitable for animals. The gloopy remnants of that spill can still be found on Alaskan beaches to this day.

These events shook the collective consciousness, and where environmental concerns had once been an afterthought or the sole territory of Greenpeace activists, our impact on the environment was being laid bare before us, impossible to ignore. We were destroying our home, and it was time to think about change. Video game narratives picked up this mantle, and began to consider what we were doing to our planet. They began presenting us with fantasy worlds—worlds not so different from our own—in peril.

It was also during this time that Japan entered into its “Lost Decade” following the collapse of its economy. A bubble of inflated real estate and asset prices had burst, leaving many wondering if the system of capitalism they had put their faith in was sustainable for the planet. There had to be some way to save the world from this fate. It was video games that began exploring these possibilities.

Just a Small-Town Boy

It is a staple of the hero’s journey for a character who will one day save the world to come from humble beginnings. RPGs in the ‘90s had protagonists like this in spades. Will from the Super Nintendo RPG Illusion of Gaia fits this bill, though we could just as easily talk about Terranigma’s Ark, or Tales of Phantasia’s Cless, or Crono from Chrono Trigger, or Ratix from Star Ocean, or Randi from Secret of Mana. They’re all variations of the same character, and at the time, one meant to be relatable to the largest demographic playing video games: young males. This choice serves a few different functions in the game besides creating a character that mirrors the player base.

Starting off as a small-town kid allows for gameplay mechanics to be introduced slowly, in a way that doesn’t break immersion. A kid from the sticks might need pointers on how to hold their own in a world where monsters roam about. But more than that, it allows the narrative stakes to slowly, but surely, be raised as the hero progresses. By starting small—Will’s first quest in Illusion of Gaia is to bring some of his father’s things to the nearby Edward Castle—more can be revealed about the world as the hero is introduced to new people, new towns, and new tales of woe. Before they realize it, the hero is joining forces with the Knight of Light to destroy a comet hurtling towards Earth.

Not only is this continual escalation a driving force for the player to keep playing and for the protagonist to keep fighting—it also presents the simple theme that seemingly small actions can snowball into something greater. This is powerful messaging, and serves as a hopeful allegory for the real world, where a seemingly small action could eventually lead to something world-changing. On an issue as huge and humanity-threatening as climate change, thinking about the hero’s journey to reach meaningful change could help motivate someone to take that first step into the unknown. Granted, the forces of capitalism and the stifling (un)work done by most elected officials creates a real barrier, but the message is at least hopeful in these ‘90s RPGs that change is possible and worth fighting for.

Are Video Games Just Games?

Video games occupy a unique space in our pop culture landscape thanks to their inherent interactivity. As the player, we are in control of the characters. While there is (most often) a predetermined path that guides us through the game, it is our physical button presses that get these characters where they need to go. Through this participatory action, we become more invested in the game worlds we play in. This makes video games a particularly powerful tool for engaging with complex systems (political, social, or cultural structures) from our own world, as they build allegorical narratives for us to experience and worlds to immerse ourselves in.

There is a long-running debate amongst game critics, scholars, and casual gamers alike on the topic of ludology vs. narratology. Simply put, is a video game a game first, or is a video game a narrative first? Should the focus be on gameplay and what we, the player, can do in the game world, or are we in it for the story? There is no right answer, as both sides of the argument have merit, but it is against this backdrop that we can start to compare and contrast ‘90s save-the-world games and modern post-apocalypse games.

I recently replayed Illusion of Gaia, developed by Quintet and first released for SNES in 1993, and what becomes immediately apparent when playing a game like this is how passive the experience feels. Even though the game is an action-RPG, you spend a great deal of time simply observing static scenes. Slowly scrolling text boxes are frequently the only thing to focus on. While it wants to engage you with its gameplay, and offers the player engaging mechanics and exciting boss battles, the narrative is clearly the focus. In making this game, Quintet reached out to award-winning science fiction writer Ohara Mariko to write the story. They wanted to tell a story that would resonate with players, and get them thinking about the fate of the planet.

While Gaia’s dialogue is clunky in parts, the game remains laser-focused in presenting its message to the player. The game features only one sidequest (collecting 50 red jewels scattered across the world), and completing that sidequest nets you absolutely nothing. The lack of reward or even fanfare for completing the task seems to ask the player, “Why are you wasting time collecting these jewels? Don’t you know the world is ending?”

Illusion of Gaia hums along at a brisk 6-8 hour playthrough time, and every location the player visits is in some way connected to the impending doom threatening the world. Will and his friends (and by extension, the player) cannot break away from the fate of the planet, and there is no time for distractions. Humanity hangs in the balance. The time to act is now.

During critical moments of the narrative, the text box is slowed to a crawl so the player reads every letter as it pops up. This is done intentionally to hammer home the story. After the final boss is defeated, our main characters stand facing an unchanging background image (for 10 whole minutes), talking about what their journey has meant. There is no razzle dazzle. The player is reading a story.

In modern games there are increasingly complex systems within which we operate while playing. Crafting systems, weapon management, skill tree optimization, battle mechanics, sidequest and NPC interactions, achievement hunting (which isn’t even part of the game itself, but functions as a meta level gamification of a video game) and more, all of which can be legitimate areas of focus for the player. The downside of all these systems is that at times they can be overwhelming, to the point that players may even drown in the minutiae of all of it, losing the script completely when trying to recenter on the game’s narrative. The dopamine hits we get from mastering these systems distract us from the despair of the post-apocalyptic world we have gained mastery over. So maybe we don’t take the narrative as seriously, because hitting sick combos with our max-level character is more fun.

Game design is pulling our attention away from narrative elements to dazzle us with spectacle and systems on top of systems. The priority seems to be that the player is playing a game.

Saving the World

In the 1990s, environmental themes drove the narrative in a number of titles. There was a palpable sense of crisis behind these stories. A sense that our own world was in peril and these games were screaming at us to do something. We were put in a position to think about why the world (both game and real) was worth saving, and these games repeatedly implored us to consider our own situation as we helped our heroes navigate theirs.

Illusion of Gaia shows us a world careening towards collapse. Will journeys across the world, and everywhere he goes, he sees the planet buckling under the weight of impending doom. Animal populations are dying out, people are falling ill with unknown diseases, slaves are traded in underground markets, and famines are decimating the population. The cause of all this is deemed to be humanity evolving too quickly. Our desire for progress comes at great cost to the natural world as we plunder and lord over nature with reckless abandon.

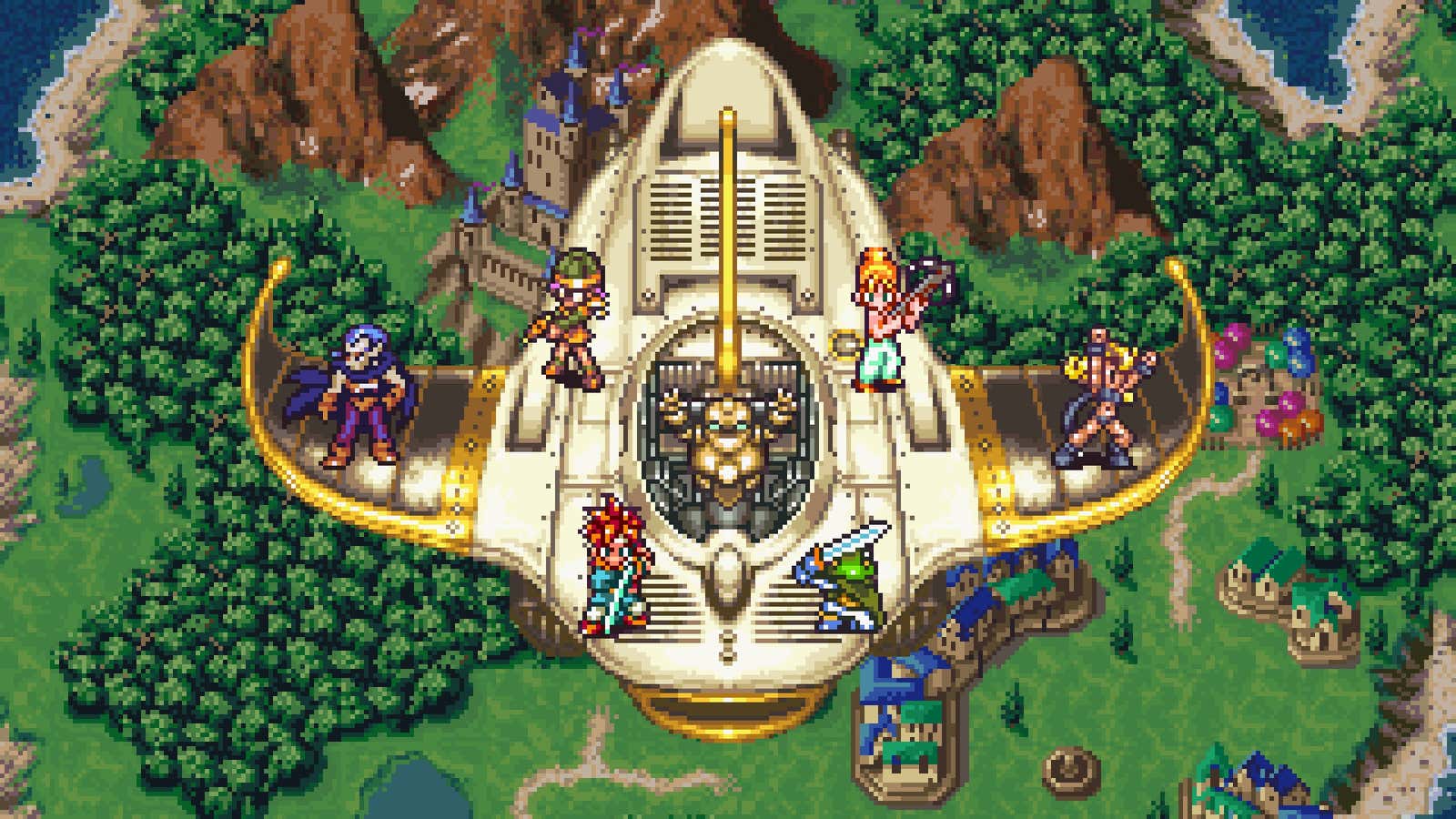

There are stories where the Earth’s natural energy (Mana in Tales of Phantasia & Secret of Mana, Mako in Final Fantasy 7) is sought after and pillaged without restraint in the name of technology, progress, and financial gain. There are stories where the future is revealed, showing how an apocalyptic event will affect the planet and why it must be stopped (Chrono Trigger even tells you “The Future Refused to Change” if you game over). Stories about the callousness and greed of humans (Star Ocean, Illusion of Gaia, Terranigma). There are even stories where our heroes must sacrifice themselves for the sake of the planet (Illusion of Gaia, Terranigma, the original narrative of Final Fantasy 7), a particularly powerful plot point that shows these heroes are acting altruistically for a future they will not see and one in which they will ultimately be forgotten.

Even as you get invested in the often-wonderful characters, the narrative is always reminding you that what’s at stake is bigger than any one of them. This is evident in a game like Chrono Trigger where all party members can be swapped out of the main party at the player’s discretion. Even Crono, the veritable hero of the whole story, can be removed from the party, showing that not even the main character matters all that much when the planet is being threatened.

Personal story beats are often minor, and only used to fluff up or sketch out some kind of background, some kind of reason for a supporting character to join the hero’s cause. Not every character needs to be analyzed like Tony Soprano. Frog, a powerful knight (and, yes, anthropomorphic frog) who can join your party, is a great character. Do we know every little thing about him? No. Do we need to? No. His brief narrative moments with his mentor Cyrus more than suffice in developing his character. His theme plays a few times throughout the game and we get hype, that’s all we need. The more pressing issue remains stopping Lavos from destroying the planet.

With so many stories focusing on saving the world from destruction, these games were asking us to think about saving the planet from our own hubris. So why is it that now, in the 21st century, as climate change becomes an even more apparent and imminent threat, we’ve moved on from saving the world of the present and have settled for living in a destroyed future?

Surviving the World

While the ‘90s saw a rush of media centered around environmental issues and saving the planet from doom, in the last decade the question video game narratives are asking has shifted from “How can we save the world?” to “How do we live in the world we couldn’t save?”

The world of the post-apocalypse is an enticing one for writers (and readers) of speculative fiction. What does society look like as it emerges from the ashes of nuclear war? Can the mysterious viral outbreak ever be contained? How does nature reclaim our cities when we abandon them? The period after a cataclysmic event has become somewhat of an ideas playground for media of all kinds, and video games are no exception.

Post-apocalypse fiction started to really take off in the post-war period following World War II. After seeing the destructive power of the nuclear bomb decimate Hiroshima and Nagasaki, and in the nascent days of the Cold War when many thought that the arms race between global superpowers would ultimately lead to complete annihilation, novels were written exploring the world after the end of days.

What is presumed in post-apocalypse fiction is that the apocalypse was inevitable. The world has already been cooked, and now it’s about surviving the aftermath. In addition, whatever the devastation may be—nuclear wastelands, climate disasters, viral outbreaks—the planet is relegated to the background. Most stories set in the post-apocalypse are more concerned with addressing a specific societal critique unrelated to any notions of saving the planet, as the planet is already a lost cause. There often isn’t a win condition that leads to the betterment of humanity as a whole. Even if the power-hungry, fascist bad guys are stopped, everyone still has to live in a shitty, hollowed-out world. Those guys just won’t be around to indiscriminately kill people anymore. The apocalypse may come up, but it is not the driving force for the characters in the story. The planet’s already been destroyed. At this point, the why doesn’t really matter.

The reason the post-apocalypse works so well as a vehicle for this kind of rumination is that the author is able to re-order society into a formation that maximizes the particular aspects of the world they wish to critique or the relationship they want to explore. Despite presenting us with a world in clear societal collapse, The Last of Us is ultimately a personal narrative. We’re not supposed to ask too many questions about how or why society is in shambles; what is being examined is the relationship between Joel and Ellie.

How do people deal with trauma? What lengths will humans go to for love? The setting of the post-apocalypse creates a perpetual state of stress that works on the characters, grinds them down, and pushes their relationships to emotional extremes that would not manifest in our “normal” world. It helps the game hit its emotional beats with extra vigor, and in our postmodern, affect-rich culture, getting to that emotion—getting hit in the feels—is what we have been conditioned to crave. Concern for the planet, or larger societal questions in general, don’t matter. We just want to FEEL Joel and Ellie’s relationship.

There are certainly video games set in the post-apocalypse that attempt societal critique, but there are arguments out there that suggest that while it might feel like something is raising awareness, or calling out a societal evil, the critique actually isn’t effective at all. There is reason to believe that even though media we consume appears to be presenting an anti-capitalist message, post-apocalyptic narratives may be reinforcing the capitalist systems that control us through something called “interpassivity.”

The concept, theorized by writer and philosopher Robert Pfaller, postulates that we feel like we participate in anti-capitalism by consuming media that essentially “does the work for us,” protesting in our stead. We feel good about that, and move on, without ever asking more meaningful questions or feeling inspired to take action. The critique of the system becomes part of the system. Intentionally. The Last of Us meekly presents an authoritarian state as a big bad lurking in the background, which gives us a chance to be the Pointing Rick Dalton Meme and say “There it is! Authoritarian! Bad!” pat ourselves on the back, and call it a day. No need to think about where we see authoritarianism in our real world. Too much work.

Even games that try to put nature front and center struggle to address the theme of environmental catastrophe with any kind of imperatives or calls to action. In Horizon Zero Dawn, the entire planet’s ecosystem is run by the GAIA AI, an advanced computer program that can terraform the land and give life to plant and animal species. It is under threat from rogue subordinate functions within the system, now sentient, that are angling to eradicate humanity as soon as possible. The game presents an ecomodernist solution to its apocalypse, the idea that technology will save the planet, even when an over-reliance on technology is also the cause of the collapse in the first place.

While there are certainly strategies that could be implemented using technology to reduce our impact on the environment, the fact that the Zero Dawn protocol puts ultimate faith in technological power gives it the same pie-in-the-sky feel as many of the things the tech giants of our world would prescribe for us. It is a world that capitalism will save. Aloy, being who she is, is a literal instrument of technology who exists as part of the GAIA system. While the GAIA system does work and technology saves the day, the more likely outcome would be something akin to what we see in Adam McKay’s 2021 film Don’t Look Up, in which the snake oil salesman CEO of an Apple/Tesla-styled tech company proposes a foolish plan to save Earth from a meteor (while profiting off of said plan) and the failure of this plan leads to humanity’s demise. I mean, we’re almost there already.

The post-apocalypse is a space of regret, of failings, of missed opportunities. And given current narrative trends, it seems to be the only space where we can imagine something different. The idea that only through annihilation can we reconfigure our lives is a phenomenally bleak outlook. When we see the post-apocalypse as the only place where things can get better, and the only place from which we can critique our present, it only fetishizes the post-apocalypse further, and makes the idea of saving our present world not a priority.

We seem obsessed with writing stories set in the post-apocalypse because we can’t imagine a way to fix our own world, we can only imagine the end. This is what Mark Fisher writes in his book Capitalist Realism. After the collapse of the Soviet Union, the alternative to capitalism had been defeated, and since, we have become so entrenched in the machinations of this system, we cannot imagine a feasible way out of it. This has only intensified in the internet age as algorithmic culture pumps drivel at us nonstop and media is reduced to being valued only as content to vulture capitalist CEOs with little respect for creative thought and ideas. We’re trapped under the immense weight of structures designed to force us to consume more and more, and critically think less and less. The only way out is to endure complete destruction and then to try again.

Video games of the ‘90s offered so much hope for the future. Saving the world was within reach. And Fisher points to environmental destruction narratives (as seen in ‘90s RPGs) as one of the few effective ways to critique capitalist systems, as they present an undeniable reality that capitalism cannot spin. Video games were on the right track in crafting narratives with themes they wanted players to take with them. We just had to be better stewards of the Earth, find balance with nature, topple power-hungry megalomaniacs and we could be all the better for it. Was it idealized? Certainly. But it was hopeful. Sadly, it feels like that ship has sailed, but it doesn’t have to vanish over the horizon. There’s still time.

Our world is in peril. This one. The one we live in right now. We can save it. It would be great if video game narratives would rise to the occasion again and start hammering this message home, instead of giving up and thinking about how we’re going to pick up the pieces. Major studios have pivoted away from stories about saving the world, and media outlets are shying away from any meaningful coverage on the issue of climate change. It shouldn’t be this way. Surely there are creative voices at these AAA studios who could take up the mantle of their ‘90s forebears. It shouldn’t be left to indie devs like Giannis Milonogiannis and his project, Eco Breaker, to get us thinking about fighting back to save our world, but it’s a start.